Managing Volatility Around the Midterms

The market expects this election cycle to cause large price moves

Midterm elections often cause volatility, and the markets are acting accordingly. Volatility futures (/VX) show the possibility of lots of price fluctuation throughout the rest of the year.

Whether it’s because of inflation, recession, geopolitical issues or something else, the market expects this election cycle to cause large price moves. While that may sound like a bad thing, options traders look forward to greater volatility.

Volatility overstatement occurs when implied volatility is greater than realized volatility. Implied volatility is the forecasted move, within one standard deviation from the underlying price in a given period of time.

It’s common to examine implied volatility over 30 days or one year. A low implied volatility means that the market isn’t expecting prices to move much, whereas a high implied volatility is the opposite.

Premium sellers—who are defined as choosing to sell options contracts instead of buying them—profit from the passage of time or being directionally correct when realized volatility is lower than implied volatility.

It’s difficult to be right consistently on direction, and the passage of time can be forecasted. Some premium sellers have opted to trade based on the assumption that realized volatility will come in lower than implied volatility.

Because implied volatility is a key variable in options pricing, options prices are high when implied volatility is high. The higher the price of an option, the farther a trade’s breakeven is from the market price.

If the market is pricing in a 10% move in the underlying via the implied volatility, but the actual move is only 5%, that’s a volatility overstatement that potentially enables premium sellers to realize a profit. For context, in the past five years, implied volatility has overstated realized volatility 77% of the time in the S&P 500.

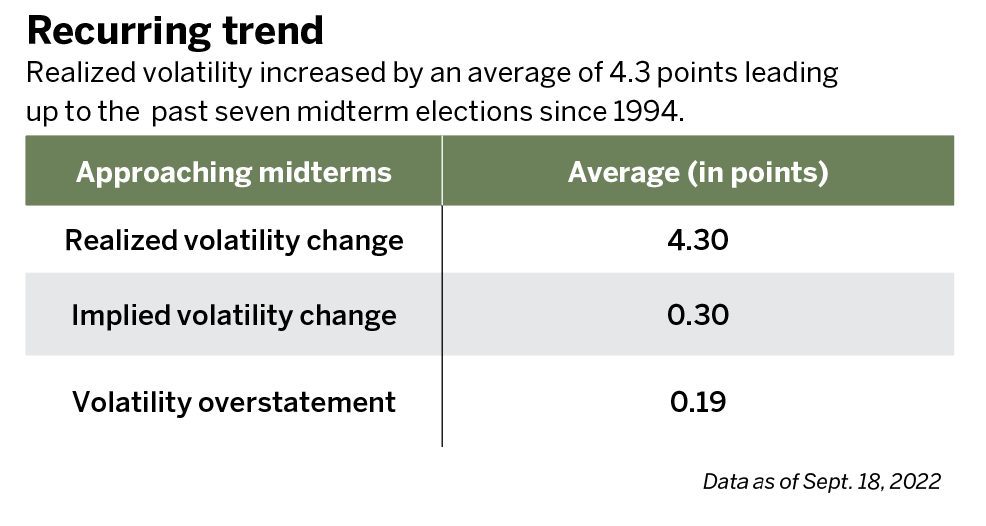

For premium sellers looking to place a trade for the midterms, it’s valuable to look into what happens to volatility in November during a year of midterm elections. Going back to 1994 and looking at the past seven midterm elections, realized volatility increased by an average of 4.3 points leading up to the election.

In the months before November of each of those years, realized volatility was 4.3 points lower than in November. The same trend can be seen in implied volatility, but to a smaller degree, with implied volatility 0.30 points higher in November than it was before the midterms.

More than 50% of the time, realized and implied volatility were both higher in November of a midterm election year than before the elections. Active investors who are day-trading futures or stock around election day should be cognizant of the increased volatility.

In terms of volatility overstatement, implied volatility was higher than realized volatility in 57% of the previous midterm elections. The average overstatement was 0.19 points, meaning the market had priced in higher volatility than was actually realized. For premium sellers, that’s the ideal scenario, and it means they could sell options that priced in larger price changes than actually occurred.

Although realized and implied volatility historically increased coming into midterm elections, it’s difficult to draw a conclusion from this data with confidence. With only seven previous occurrences, the sample size isn’t large enough to say confidently that one thing will or will not happen.

Regardless, if investors are using stocks, options or futures, it’s important to be mindful of potential volatility around events like elections.

Eddie Rajcevic, a member of the tastytrade research team, serves as co-host of the network’s Crypto Corner and Crypto Concepts. @erajcevic11