No-Choke Collars

Instead of purchasing puts to protect a portfolio, consider the zero-cost collar

Some think of investing as a noble calling. It provides an opportunity to realize a profit, reduce the cost of capital, help create jobs and participate in the success of American industry. No wonder investors feel good when the markets are strong. But they worry when markets decline so they need a hedge. They can choose smart hedges or not-so-smart hedges, so let’s look at examples of both.

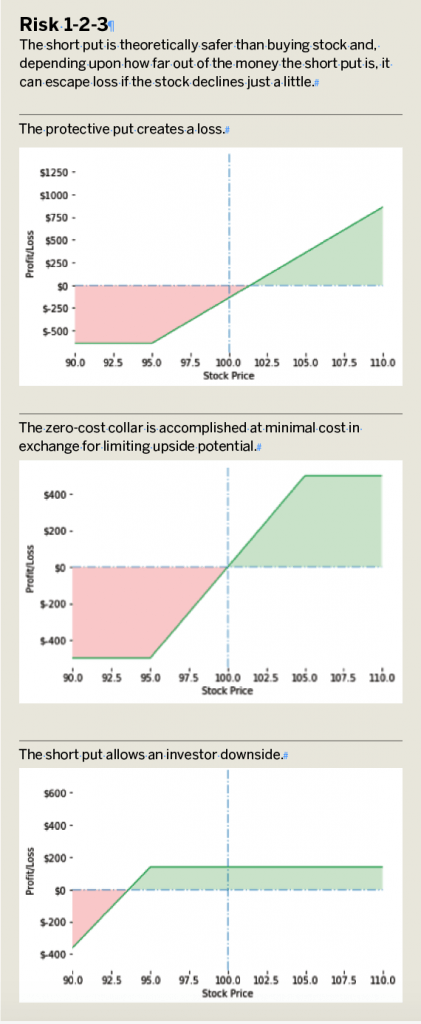

Investors sometimes buy puts below the current stock price in an attempt to buffer against possible declines in the stock price. They call the strategy a “protective put.” But often, the price doesn’t decline at all or declines less than the value of the protection the investor purchased. The investor is then out money for the cost of the put. That’s a bad investment strategy—overpaying for insurance.

But investors have two good alternatives to the protective put: the zero-cost collar and the out-of-the-money put.

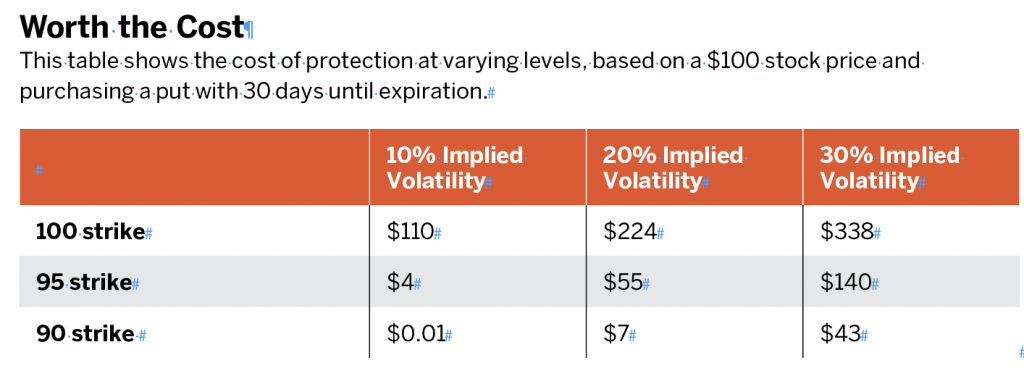

“Worth the cost,” below, shows how much it costs to purchase protective puts at varying levels. The implied volatilities are also listed—the higher the implied volatility, the higher the expected movement of the stock price and higher the cost of the put.

The traditional long put hedge doesn’t work as an overall trading strategy. First, investors who buy puts often overpay. The strategy becomes popular when a market has declined or investors expect an event to occur. Both push option “insurance” to its highest point. It’s common to see volatility of 20% or 30%+. So instead of purchasing insurance for $4, the investor is paying $55 or $140+. But many times over the past decade, observers have seen that the market’s “bite is rarely as bad as the bark.” The market hasn’t declined as much as expected and didn’t stay down as long as feared. Protective puts can expire worthless.

Second, investors often purchase the far out-of-the-money puts because they’re less expensive than closer out-of-the-money puts. The farther away the put’s strike price is from the stock price, the cheaper the put. But that also means that a less expensive put has less protective value. The stock has to decline to fairly close to the put’s strike price before that put really starts to provide a hedge. The closer the put’s strike price is to the stock price, the more protection it provides. The farther away the put’s strike price is to the stock, the less protection it provides. That’s why the farther out of the money the put is, the cheaper it is. So, if the stock does decline, but not so much that it reaches that far out-of-the-money put’s strike price, the investor might make a few bucks on the put but lose more money on the stock.

A better alternative

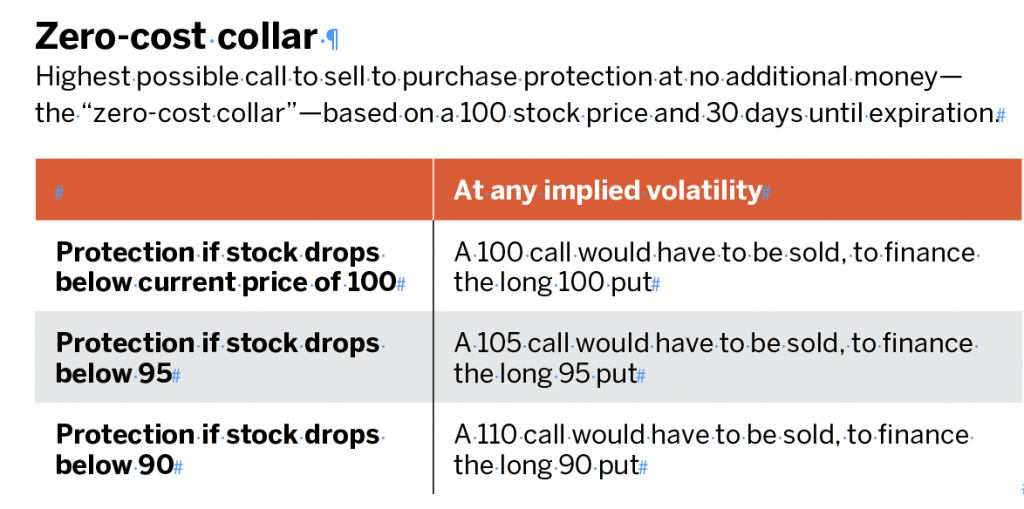

With what’s called a zero-cost collar, an investor buys a put and then “finances” it with a short out-of-the-money call above the market. Think of it as a covered call that’s “paying for” the long-put protection. This is a preferred method of adding protection because it’s exchanging the costs of the long put, with the reduction in upside potential. After all, by selling the call short, the investor is limiting the upside, but that’s the trade-off the investor has to make to reduce the cost of the protective put hedge. (See “Zero-cost collar,” below.)

The zero-cost collar provides a way to purchase protection when worried about a decline. The call enables an investor to buy protection with little to no outlay of cash. It tends to provide better results over time because the investor is not locking in the cost of the put if it’s not used. The downside is that while the outlay of capital is technically “zero,” the true cost is the upside potential the investor loses in exchange for having zero cost. But the risk of losing out to the upside may not be a consideration for investors concerned about losing money to the downside.

An even better alternative

A better alternative to the protective put—and even to the zero-cost collar—is to sell an out-of-the-money put. Instead of purchasing protection, the investor ditches the shares of stock and sells the out-of-the-money put. It’s theoretically safer than buying stock and, depending upon how far out of the money the short put is, it can escape loss if the stock declines just a little. Additionally, the short put can require considerably less money than owning the stock with the collar.

The three risk graphics in “Risk 1-2-3,” below, compare the three strategies.

Every investment balances tradeoffs of potential profit and risk. Choose how much risk to take for a given profit. Don’t limit risk in ways that make it much harder for the investment to profit. That’s what the protective put does, and that’s why investors should consider collars as a hedge and short puts as an alternative to buying stock.

Michael Rechenthin, Ph.D., (aka “Dr. Data”) is head of research and data science at tastytrade.