99 Economic Problems, but a Housing Meltdown Ain’t One

Don’t look for high housing prices to tumble anytime soon. It’s not a bubble.

has an asking price of $499,000.

The average price of single-family homes has increased for 40 consecutive quarters, and the Federal Reserve is hiking interest rates to curb inflation. It’s a combination that many fear will lead to a housing crisis.

“Another housing bubble?” asks Fortune magazine.“We’re skating close to one,” warns a Realtor.com economist. “Signs of a housing bubble are brewing,” declares CNN.

Luckbox doesn’t agree.

The housing sector has solid fundamentals, and stock in some construction companies is trading for less than the sum of their parts. Let’s look at how the economists at the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank view the situation.

The view from Dallas

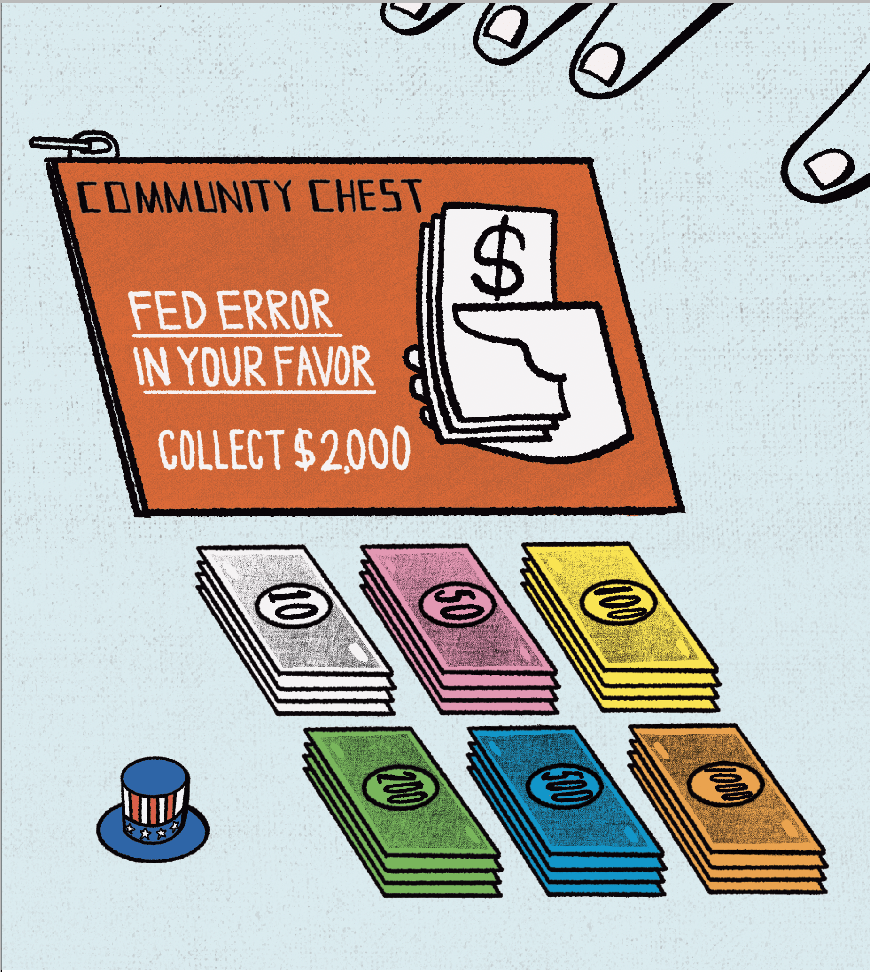

The sizable gain in house prices over the last two years doesn’t constitute a bubble, according to Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan and his team. They noted in a March 29 blog post that “shifts in disposable income, the cost of credit and access to it, supply disruptions, and rising labor and raw construction materials costs are the economic reasons for sustained real house-price gains.”

Despite higher costs in the “3 Ls” of housing—land, labor and lumber—the Dallas Fed said it did not foresee a correction that would in any way resemble the housing crash of 2008.

Back then, house prices fell more than 60% in Florida, Nevada and Arizona as the frenzy of Ponzi-style speculative buying crashed to a halt. Today, those three states are among the strongest markets for first-time buyers and retirees as the population continues to shift to the Sun Belt.

As the Dallas Fed notes, the financial position of American consumers has improved over the last two years, and the housing sector is not in the grips of a frenzy of speculative buying. In May, the number of mortgage delinquencies—defined as a homeowner late on payment for 90 days—declined for the seventh consecutive month.

That’s just one positive data point on the state of current incomes. Here’s another: During the 2008 housing bubble, Americans spent 7.2% of their disposable income on housing. At the end of 2021, it was just 3.8%.

The way home loans are configured these days is also contributing to stability in the housing market, according to Marina Walsh, vice president of industry analysis at the Mortgage Bankers Association.

“Given the nation’s limited housing inventory and the variety of home retention and foreclosure alternatives on the table across various loan types, the probability of a significant foreclosure surge is minimal,” Walsh said. “Borrowers have more choices today to either stay in their homes or sell without resorting to a foreclosure.”

Supply and

demand imbalance

New construction has been strong at the start of 2022, with the fastest growth since 2006, analysts noted. But supply still struggled to keep up with demand.

Some of today’s supply problems took root after the 2008 crash. That downturn forced some homebuilding companies out of business, and the survivors remained reluctant to start building again well into the next decade. Lots of construction workers retrained for other careers, and labor is still in short supply.

Meanwhile, millennials—the largest generation in America—are beginning to settle down and buy their first homes.

These factors compound a national supply gap of 3 million homes, as measured by the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp., better known as FreddieMac. Other organizations suggest that number could be as high as 5 million.

Although a precise figure remains elusive, there’s little doubt that it will take years to close the gap, especially with builders coping with supply chain challenges and rising costs.

In a balanced market, the U.S. typically has roughly six months of housing inventory. But after years in a sellers’ short market, the nation has only 1.6 months of inventory, according to RealtyTrac, an online marketplace for foreclosed properties. The national homeowner vacancy rate in the first quarter of 2022 fell to its lowest level since the U.S. Census Bureau began tracking the measure in 1956.

Geographic shift

The federal government responded to COVID-19 with measures aimed at forestalling foreclosures and providing relief on government-backed mortgages. Those efforts prevented a panic of distressed home sales that could have occurred when hard-pressed homeowners sold their assets at deep discounts.

The policy successes built on the Dodd-Frank Act’s reform of subprime lending practices, another major restraint on speculation in the housing market over the last decade.

Today, consumers can no longer obtain adjustable-rate mortgages that can be subject to an unexpected surge in interest rates. Would-be homeowners with a credit score under 620 are unlikely to qualify for a loan, and buyers are required to make a down payment of at least 3% of the price of a house.

But even though those restrictions limit the ability of lower-income Americans to buy a house, the market has remained in a major supply shortage.

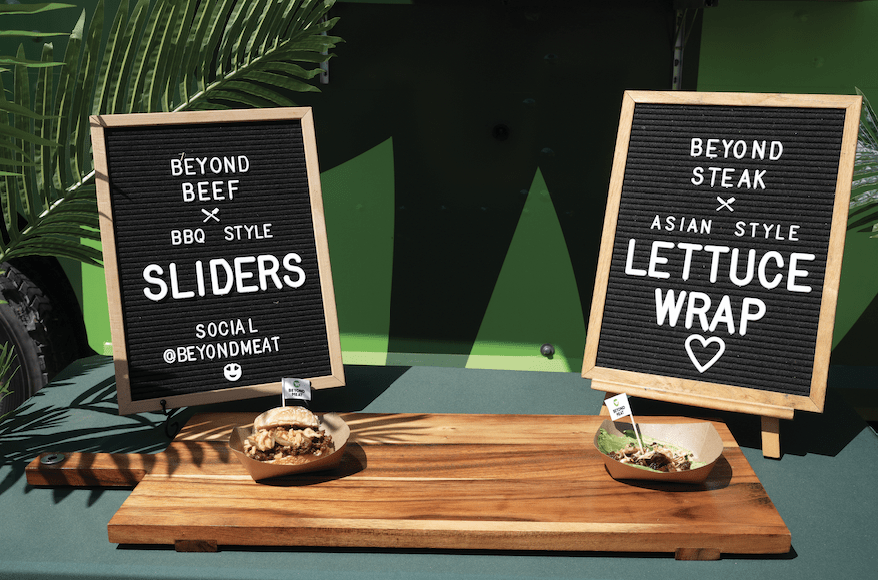

That hasn’t stopped some people from moving, though. During the pandemic-induced Great American Move, remote working has enabled the population to leave the Big Six 24-hour cities of Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

Many settled in smaller 18-hour towns, such as Atlanta or the Florida cities Orlando, Tampa and Jacksonville. Other 18-hour places range from Austin, Texas, to Boise, Idaho, and Las Vegas to Scottsdale, Arizona.

Eighteen-hour cities usually have populations of less than a million and tend to shut down for a few hours every night. They generally provide the amenities and opportunities of the Big Six metropolitan areas but at a lower cost of living and lower cost of doing business.

“There was already a kind of movement of that segment out to the suburbs as the older edge of the millennials are starting families and looking for more space and maybe school districts,” Anita Kramer of the Urban Land Institute told Forbes last October. “That has been accelerated by people’s experience working from home and schooling from home and wanting more space. If they ever have to go to the office, it would be for a smaller number of days. Their commute is no longer as onerous as it once was.”

Local restrictions

Even with a tight supply of houses, many local units of government don’t make it any easier to build. Roughly 25,000 regulatory bodies regulate housing in the United States, according to the Federal National Mortgage Association, or FannieMae.

What’s more, neighbors often oppose construction of townhomes and condominiums because they fear heavy traffic and strained local resources.

Meanwhile, demand for single-family homes appears likely to increase—not decrease—because of key market fundamentals.

First, Generation Z, the cohort born between the mid-’90s and the 2010s, is more financially stable than previous age groups, and they’re preparing to purchase their first homes. They’ll compete for starter homes against retiring baby boomers looking to downsize or relocate to the Sun Belt.

In addition, companies like BlackRock (BLK), Tricon Residential (TCON) and private equity giants continue to invest in single-family homes to capitalize on strong rentals and robust cash flow. They’re buying just 1% to 2% of the homes sold nationally, and their share is expected to increase.

Trade the gap

None of this means that housing prices can’t decline. A haircut correction for prices in the 10% range is on the table, but don’t expect a plunge remotely like the 2008 housing crisis.

Today, markets depend on the Federal Reserve’s actions. As the central bank hikes interest rates, it may deter buyers from purchasing larger homes. Naturally, fear of a recession could alter buyer sentiment and potentially cool off the market.

But the central bank can’t print more houses.

Garrett Baldwin is a commodity and trade economist who serves as Luckbox’s editor at large. He actively trades value and momentum stocks and wagers on sports and prediction markets.

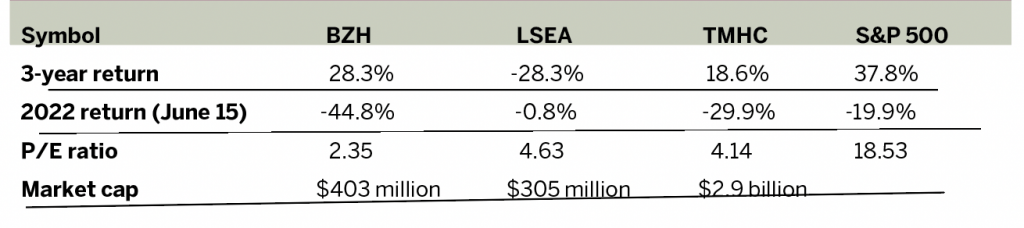

LESS THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS

In June, Luckbox discussed an investment strategy called “rational liquidation value,” which is how much cash investors would receive for their stock if a company liquidates.

The current broad market sell-off has presented an opportunity to buy stock in three homebuilders that are trading under a rational liquidation price. They’re valued at less than the sum of their parts.

– Landsea Homes (LSEA), a California-based homebuilder, is trading at less than five times earnings and 58% of its tangible book value. The company announced plans to buy back $30 million in stock at $8.11. But its tangible book value is $12.11, and its net asset value is $11.20.

– Taylor Morrison Homes (TMHC), a custom homes designer, trades near its tangible book value of $28.14, but its price-to-free cash flow of 5.3 makes it quite attractive. The company has benefited as the population has vacated megacities in favor of smaller towns, and it has announced plans to repurchase $500 million in shares. Should consolidation accelerate in the industry, TMHC could become an attractive takeover target.

– Beazer Homes (BZH), a Georgia-based builder operating in 13 states, trades at 42 cents on the dollar. Beazer now trades at three times earnings and a price-to-projected cash flow of just 0.19x.

If buying these stocks sounds like too much of a long-term hold strategy, look at Beazer’s options chain. Traders could sell the Beazer Homes on Aug. 19, $8 put in an inexpensive trade, or explore a spread. If the stock doesn’t fall below $8, traders get to keep the money. But in the worst case, they’ll find themselves assigned a more affordable stock than today and even lower than its liquidation value.

Where Capital Will Flow

Housing stocks have felt the pinch of the market’s brutal sell-off over the first five months of 2022. The SPDR S&P Homebuilders Exchange-Traded Fund (XHB) is off 25.3% to start 2022.

Fund managers are talking about buying cheap “cash flow” to capture as much green stuff as possible and toss it under the mattress. As price discovery and valuation compression continues, they’re causing a rotation to quality and value.

But regardless of economic concerns, strategic investors should recognize that capital will flow into things Americans need, not what Americans want. That includes oil, shipping, utilities, mid-sized and community banks, and, yes, housing.