A Short History of Video Streaming

Television's third incarnation is changing—and it's not for the better

The era of “Television 3.0” dawned last summer when streaming video topped cable TV in viewership for the first time. Let’s take a couple of steps back in time to remember how we got here.

After World War II, antennas sprang up across the land as broadcast television transformed the delivery of entertainment and information. The number of households with TV sets exploded from 9% in 1950 to 90% in 1960, according to the Library of Congress. Think of broadcast as TV 1.0.

A few national TV networks and smattering of local channels seemed like enough for a while. But before long, viewers wanted more. The seemingly unlimited choices brought by cable television, which we’re calling TV 2.0, ushered in another transformation.

It happened almost as quickly as the spread of TV in the ’50s and proved nearly as pervasive. In 1970, 8% of households subscribed to basic cable. By 1990, 60% had basic, and half of those viewers also had premium channels. Cable reached its peak of 100 million households in 2013.

But then something happened. The subscription base for cable began shrinking as Americans turned to streaming video—the phenomenon we’re calling TV 3.0. Last summer, streaming supplanted cable as the most-watched form of television. The numbers appear in an article on p. 32 of this issue.

The reasons behind the shift to streaming won’t shock most TV fans. First, subscribing to streaming services usually costs less than cable. Second, streaming enables viewers to watch their favorite movies and series whenever they choose, instead of at an appointed time dictated by some faceless cable company technician.

That may sound great, but it touched off open warfare.

The streaming wars

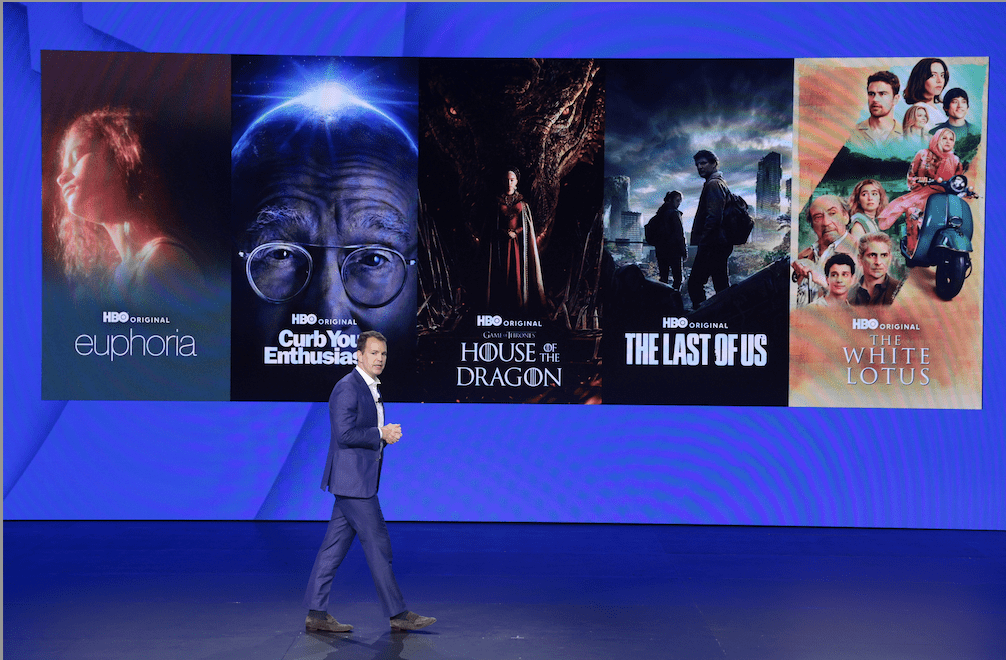

By the end of 2019, streaming services that included Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, Disney+, HBO Max and Apple TV+ were locked in a fierce competition for subscribers.

The struggle became so heated it earned the name “streaming wars.” The combatants fought with such abandon that their business plans didn’t seem to include a path to profitability. Companies wanted market share immediately. Healthy return on investment would have to wait.

To that end, streaming services began to produce their own movies and series. They pulled out the financial stops by hiring A-list stars and big-name directors. They spent freely on computer-generated imagery that can typically cost $570,000 per minute.

The cost of creating shows skyrocketed. Netflix paid $30 million per episode for the fourth season of Stranger Things. The eight-episode first season of Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, which airs on Amazon Prime,cost $715 million, including $250 million just for the rights.

To some degree, television began to equal or even eclipse Hollywood movies for artistic innovation and integrity. The current era even became known as the “The Second Golden Age of Television,” more highly regarded than the first “Golden Age” of live broadcasting in the 1950s.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic struck, forcing people to stay home to avoid catching the disease and giving television a boost in viewership. But the day has only so many hours, and the time spent watching streaming video reached a plateau.

It began to look as though streaming couldn’t attract more viewers or nudge existing viewers into watching more video. The time had come to stop concentrating simply on adding viewers and instead figure out how to make a profit.

Chaos ensues

The media declared the streaming wars over sometime in 2022 but had a difficult time naming the industry’s next phase. Streaming services seemed to go their own ways without providing an overriding theme other than the search for financial sustainability.

One shortcut to black ink on financial reports was spending less on the actors, writers and directors who create prestige productions. A number of streaming services have canceled high-priced production deals.

Streaming providers are also choosing original programming designed to appeal to wider audiences and turning their backs on shows for niche audiences. The “Golden Age” is dead on arrival.

Cost-cutting can occur at home, too. Disney, for example, is laying off 7,000 employees this year, which is 3% of its workforce of 220,000. It hopes to save $5.5 billion as a result. At the same time, the company’s raising prices.

In another example, Netflix began cracking down on sharing passwords, a practice that had enabled multiple consumers to take advantage of a single account. The company rolled out restrictions country-by-country, and the new constraints are scheduled to reach the United States in the next few months. It’s hiking prices, too.

Meanwhile, streaming services are experimenting with advertising by offering some content for free if viewers are willing to sit through commercials, many of them repeated almost endlessly. For older viewers, it can feel like a return to broadcast television when they reacted to breaks in the action by turning off the sound or by ducking into the kitchen to make a sandwich.

Though disorder reigns, some believe a new pattern will emerge.

A possible scenario

“Bundling” could become the next big thing in video streaming. Individual services appear ready to join forces and offer themselves as packages. That worked for cable when providers made paid TV available in conjunction with internet connections and phone service.

But the new era of bundling will come with fewer prestige shows as the streaming services continue to cut costs. Consumers will be getting less value despite higher prices. Plus, they’ll have to learn to live with interruptions caused by an increasing number of ads.

The era of streaming TV 3.0 will continue, but the “Golden Age” is fading to black.

Creator Wisdom

On the influential podcast Colin and Samir, hosts Samir Chaudry and Colin Rosenblum offer expert advice for creators of streaming video content. At last count they had an audience of more than 1.2 million listeners. Luckbox spoke with Chaudry, one half of the duo.

Streaming’s ascendant. What’s thefate of cable and broadcast TV?

Because of streaming, we’ve gotten to a point where we have choice, which is very interesting from a consumer perspective.

When I was a kid, I would turn on the TV Guide channel to see what was on MTV or Nickelodeon for the next three hours. If you missed a show, you’d have to wait a whole cycle to see it. That was a lean back experience of saying, “Hey, I’m going to turn this thing on. You tell me what’s on right now, and I’ll let you decide for me.”

With streaming, you can watch what you want, when you want. But cable isn’t going away. There are times when we don’t want so much choice. We want a lean back experience rather than a lean in experience. There’s always a spectrum of options, and those range from incredibly active, like pursuing entertainment on Twitter, to incredibly passive, like just thinking “entertain me.”

How important is YouTube Shorts to the creator economy?

YouTube has been at the center of the creator economy in that audiences were really connecting to this new “For You” style. Creators were able to build large followings, and the creator economy built out to the point where there was a system for brand ambassadorship and brand deals. Advertisers are willing to spend directly with creators.

When I look back at what our channel did last year with Shorts, we got about 130 million views, and that probably gained us 300,000 subscribers. So, the brand of Colin and Samir has risen.

TikTok has a strong algorithm and delivers content meant to entertain — not to engage, correct?

And there’s also the intent of the audience. When you open TikTok, it’s already playing a video. When I open YouTube, I have to search. That’s an important distinction. YouTube is a search engine—TikTok is actually giving me something immediately.

What do you think of the proposed ban on TikTok?

People suggest a TikTok ban is unprecedented. But, there have been times when

the U.S. has censored media that have been spreading ideology, right? TikTok drives culture and ideology in a way and at a pace that we’ve never experienced before, and it’s very scary for it to not be U.S.-owned.

YouTube pays content creators 55% of the ad revenue they generate. Is there any competitive pressure to change the payout?

Since the beginning, I’ve looked at YouTube ad revenue as found money. I’ve never put it into a budget. I’ve never put it into projections. I’ve never expected it to be there. It’s too volatile and for us can vary from $7,000 a month to $49,000 a month.

We have no control over how much we get paid from YouTube. That’s a deal that’s made between an advertiser and YouTube—based on the volatility of the ad market and our viewership. What I do have control over is picking up the phone and pitching my media to a sponsor.

We can monetize by going direct to our audience through subscriptions, right? We can sell merchandise, or we can find advertisers that fit our niche and sell premium advertising directly into the content. That’s how most creators make money through brand deals and partnerships.

Without question, we should be compensated by YouTube for supporting their environment. They’re running an ad business. We’re providing the content. We should be compensated.

At the same time, they don’t take a percentage of the thing I have the most control over—sponsorship—which generates 85% of my revenue. They don’t charge me to upload, and there’s no fee for me to use their platform to reach my audience—which I am selling brand partnerships into.

There’s a three-legged revenue stool of sponsorships, subscriptions and merchandise—plus the found money of ad revenue. What should new creators target first?

Sponsorships. We have an incredibly robust system in the creator economy right now for sponsorships. Good deals are available if you’re creating something of value. A lot of creators can make stuff, but it’s not reaching a specific audience. That’s not going to be great for sponsorship.

So, you have to have a hyper-defined understanding of who your audience is and the value you provide to your audience. If you can understand that, you can find brands that want to do the same thing.