Amazon Primeval

As the company extends its reach into nearly every aspect of American life, it’s trying to shift the conversation away from antitrust

For years, Amazon hadn’t faced the antitrust scrutiny that plagued rivals like Apple and Alphabet. But now Jeff Bezos finds his firm at the center of an intense ideological battle over the role of big tech companies in the U.S. economy.

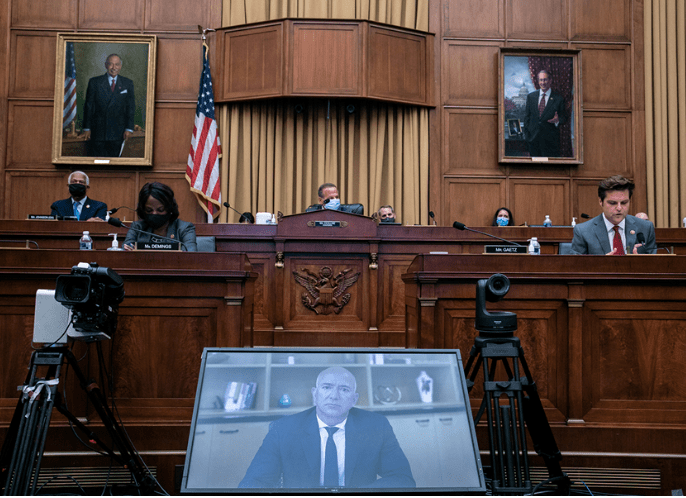

In October 2020, Congress questioned the business practices of the technology behemoths and recommended remedies for their excesses in a report called Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets. It rivals a Tom Clancy novel in length, and it convinced Amazon to try to shift the focus of the public narrative away from regulatory reform.

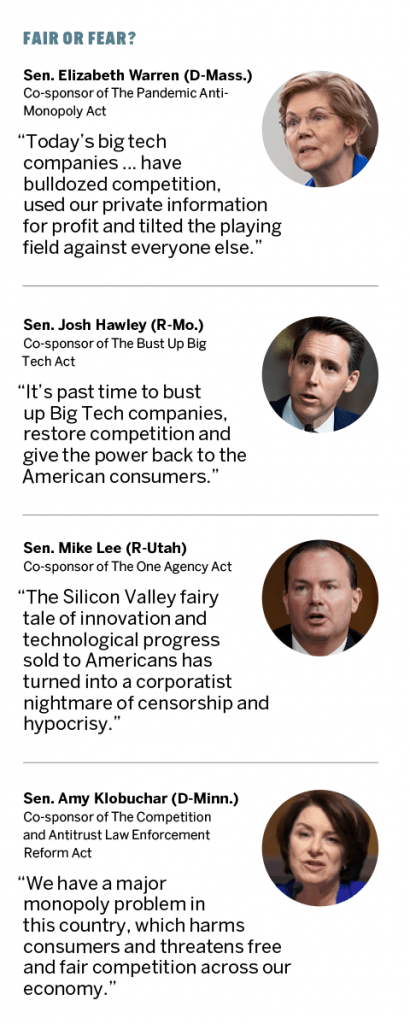

Meanwhile, Congress remains divided over whether to rip giant tech companies asunder through antitrust action. It should take drastic action, according to such luminaries as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.); Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes; antitrust scholar Tim Wu, who’s on President Biden’s National Economic Council; and Lina Khan, Biden’s nominee to head the Federal Trade Commission.

Congress could also follow the advice of Federal Communications Commission head Tom Wheeler or former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers Jason Furman. Both favor regulating big tech the way the European Commission has tried, which includes requiring companies to take responsibility for anything illegal that’s distributed through their sites and preventing them from giving preference to their own services over those of rivals.

Whoever’s advice prevails, give Amazon credit for a rare feat. Antitrust concerns have united firebrand politicians on the left and right. The issue has spurred Sens. Warren, Mike Lee (R-Utah), Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) into action.

During a confirmation hearing, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) said he looks forward to working with Khan. The gesture was a rare endorsement for government intervention from the Texas senator.

As Warren said so many times during her unsuccessful bid for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, she has a plan. This time, it’s a plan to investigate and break up firms like Amazon. What’s more, Klobuchar and Hawley have both laid out their plans for action in their books on antitrust.

In her book Antitrust: Taking on Monopoly Power from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age, Klobuchar blames Robert Bork’s actions in the 1970s and the conservative movement of the 1980s for creating the conditions that gave rise to modern monopolies.

Bork, whose Supreme Court nomination was rejected by the Senate in 1987, had argued that a primary purpose of antitrust action should be to lower consumer prices. In the 1980s, Reagan Republicans opposed government intervention in business in general.

Klobuchar offers 25 policy ideas to combat monopolies, including overturning Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the court case that prohibits government from restricting political contributions by corporations, unions and other organizations.

Hawley writes for a right-wing audience in his book, The Tyranny of Big Tech, offering a “red meat” narrative centered on how big tech stifles conservative voices. It’s billed as “the book that big tech doesn’t want you to read,” yet it’s selling on Amazon. Go figure.

Hawley also alleges in the book that Amazon began “ripping off its own vendors by the late 2010s, according to the FTC.” Amazon gathers data about customers of third-party sellers who use its site and then capitalizes on that information by launching its own competing products. To many, that alleged activity lies at the core of the antitrust question about Amazon’s role in commerce.

Should Amazon operate as an e-commerce platform while it sells its own branded products in competition with its own sellers? Amazon offers cheaper alternatives that range from yoga mats to batteries in its AmazonBasics line.

Moreover, critics complain that it doesn’t share the data with the vendors who generate it. That could help explain why Amazon-branded batteries now outsell Duracell on the Amazon platform.

The report from Congress puts it this way: “Amazon’s pattern of exploiting sellers, enabled by its market dominance, raises serious competition concerns.”

Rigged searches?

Allegations also swirl about pay-to-play marketing. The Federal Trade Commission contends that third-party products rank higher in Amazon search results if the seller buys other Amazon services, like cloud computing.

Hawley suggests that Amazon prohibits sellers from offering lower prices on other e-commerce platforms.

What’s more, Washington is again rehashing the untimely demise of Diapers.com, a widely cited case study of Amazon’s supposedly ruthless approach to competition.

Back in 2009, Amazon wanted to purchase Diapers.com parent Quidsi. After Quidsi refused, Amazon slashed its prices on diapers and other baby products by 30%, according to Khan’s Yale Law Journal report, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.

Khan noted that Amazon was “on track to lose $100 million over three months in the diaper category alone.” But Bezos’ strategy weakened Quidsi, forcing it to put itself up for sale.

Walmart made the best offer, but Khan said Quidsi executives chose the lower Amazon bid “out of fear.” After buying and shutting down Quidsi sites, Amazon immediately hiked diaper prices.

When the alleged Diapers.com power play came up during a Congressional hearing, Bezos testified that he didn’t remember it.

Monopoly power?

Congress said in its report that Amazon “has monopoly power over many small- and medium-sized businesses.” One reason is that too many small businesses “do not have a viable alternative to Amazon for reaching online consumers.”

Amazon “has engaged in extensive anticompetitive conduct in its treatment of third-party sellers,” the report also stated. Tales of Amazon supposedly leveraging power over small businesses abound on blogs, Reddit posts and chat forums.

Take the case of Molson Hart, founder and CEO of Viahart, a manufacturer of plush animals and other toys. Each year, Hart recounts his business activity on Amazon.

In 2020, 93.4% of Viahart’s sales came from Amazon. Its own website generated just 1.3% of sales, eBay represented 1.5% and Walmart accounted for 3.4%. As Hart noted, distinct advantages come with selling on Amazon. The company’s incredible logistics enable it to reach any U.S. customer in two days. Yet, he criticized what he views as the extreme difficulty of relying on Amazon. He even described his seller relationship as “being Amazon’s bitch.”

In 2018, Hart’s company paid Amazon $1.95 million for storage, marketing, discounts and other expenses. Even so, he said, Amazon doesn’t care if he fails or leaves. Viahart’s contribution amounted to 0.014% of Amazon’s revenue.

“There are thousands of companies out there eager to take our place,” Hart said.

He also noted that Viahart has nowhere else to sell as successfully and contended that Amazon leverages that knowledge. He estimated that a suspension by Amazon would likely plunge his company into bankruptcy within six months.

But Amazon drives a hard bargain. For every $100 in sales on his Amazon store, Viahart receives just $48.25 in return. Walmart’s payout to Viahart comes in at $54.50, and eBay pays $57.50. On its own website, the firm generates $83.10 for every $100 in sales.

But good luck promoting a tiny website to the masses.

Then there’s the arbitrary nature of Amazon’s payouts to third-party merchants. Amazon pays sellers based on the age of the account and the associated risk—as decided by Amazon.

Inconsistency can become troubling, too. Payments might arrive daily or might be spaced 45 days apart, according to Hart, who added that 45 days can feel like a long time after manufacturing and shipping products.

Such actions could represent another anticompetitive problem, said Lara O’Connor Hodgson, president of Now Corp., a system that helps businesses receive immediate payments. Amazon’s accounting practices could affect vendors’ credit and cash flow, she noted.

Amazon’s largest lender is its vendor network, Hodgson said. If the company has 45-day payment terms, Amazon enjoys the equivalent of short-term, zero-interest loans from its vendors, she maintained. (See Never let a crisis go to waste, below.)

Do Americans care?

Negative stories about vendors’ Amazon experiences are gaining the attention of more Americans. Small Business Rising, a coalition of entrepreneurs, is spending big to tell the public about Amazon’s impact on their livelihood. In addition, it’s lobbying Washington to break up big tech and consider policies to “level the playing field.”

The coalition is striving for those goals at a time when the public is becoming more skeptical of Amazon’s policies. A CNBC/Survey Monkey survey of roughly 10,000 Americans found that 59% believe Amazon is bad for small businesses, while 22% think the company benefits small businesses. Just two years ago, 37% thought Amazon was bad for small businesses, and 33% thought it was good.

Yet that doesn’t stop consumers from using the Amazon platform more than ever before. The firm has signed up 147 million Prime members in the United States. While Americans might believe Amazon hurts small business, they put their own convenience first.

Co-opting the narrative

Amazon has become one of the fastest-growing spenders on lobbyists. Back in 2013, it was already shelling out a hefty $3.5 million on lobbying, according to OpenSecrets, the website of the Center for Responsive Politics, a non-profit research group.

But by 2020, Amazon’s $19 million lobbying tab was second only to Facebook’s outlay, as reported by Public Citizen, another non-profit that tracks lobbying spending.

OpenSecrets also noted that Amazon had recruited the vast majority of lobbyists from the ranks of former government employees, a heavy commitment to revolving-door hiring. Those lobbyists have contacts in government and deep knowledge of the regulatory process.

One goal of Amazon’s extensive lobbying effort is to keep the government’s hands off of its business. And even many of those who believe Amazon is damaging small business would argue that over-regulating the company would distort the free market or encourage Congress to pick winners and losers.

But Congress creates policy. The government’s alphabet soup of agencies write and enforce regulation. That’s why corporations and their lobbyists have shifted some of their attention to the latter.

One can draw a straight line from Amazon’s lobbying efforts to its expansion into new markets.

Sketchy alliances

Amazon began lobbying the U.S. Postal Service in 2012. A year later, it announced a contract for the USPS to start Sunday delivery of Amazon packages.

Many praise Amazon’s partnership with the USPS. The post office can use some help because it has struggled with the transition from mail to email and bears the burden of paying pensions.

The relationship with Amazon has breathed some life into the USPS, which now makes more money from package delivery than First Class Mail.

For many Americans, the convenience of ordering from Amazon outweighs concern for the rights of entrepreneurs and workers.

But Amazon has established a pattern of engaging in cooperation and then becoming a competitor. So how long will the partnership with the USPS last? New data suggests not too long.

Supply chain consultant MWPVL International noted last fall that Amazon is replacing the USPS with its own network. Amazon shipped 67% of its own packages to consumers in 2020, the firm said. That figure is up from 50% in 2019, and MWPVL expects it will surpass 85% by 2023.

That’s not all Amazon is doing to build its network through influence. It began lobbying the Department of Agriculture in 2006. A year later, it launched its grocery delivery service.

In 2013, it began lobbying the Federal Aviation Administration. A year later, it started testing drone deliveries.

That same year, Amazon started lobbying the Treasury Department. It would soon reach a deal that saw the state of Texas drop demands for $269 million in back taxes.

In 2016, the company began lobbying the Department of Defense. The reason? To expand the already stunning reach of Amazon Web Services, or AWS.

Following the launch of AWS in 2006, the company pursued large government contracts. Under the Obama administration, the government shifted away from costly physical data centers to using AWS.

Amazon claimed in 2012 that 2,000 public sector organizations used Amazon Web Services. In 2017, Amazon won a contract with U.S. Communities, a co-operative-purchasing coalition, to provide Amazon services to 90,000 local governments.

As a result, Amazon wields significant power over government information and has a platform for advocating public policy.

Small world

Amazon’s hiring practices can seem like attempts to buy influence. Last November, it hired Jeff Ricchetti, the brother of President Joe Biden counselor Steve Ricchetti. The timing aligned with Biden’s 2020 statements calling for higher corporate taxes on tech firms. A coincidence, right?

Of course, Ricchetti’s hiring doesn’t quite compare with Amazon’s biggest influencer. In 2015, the firm hired former Obama White House spokesperson Jay Carney. He serves as the company’s senior vice president of global corporate affairs.

Why hire Carney? Was it because he once worked as a newspaper reporter and knows how to influence op-ed pieces? Or because he was then-Vice President Biden’s press secretary a few years ago? Either way, Carney once served the leader of the free world, and now he serves Amazon. He’s taken to the job by using Twitter and media outlets to unleash his wrath upon reporters and politicians, reportedly at the direction of Bezos.

Carney’s also championed his employer’s cause on the issues of frequent truck accidents, the unsuccessful unionization attempt at a fulfillment center in Alabama and the company’s piddling federal income tax bill.

In a New York Times op-ed, Carney even bragged that the firm raised its wages to $15 an hour to address criticism from Sen. Bernie Sanders, without mentioning the company hires temps and independent contractors for less than that amount.

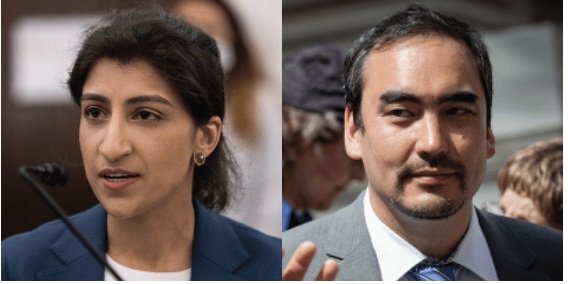

Widespread boycotts won’t quell Amazon’s power. The fate of Amazon’s influence may come down to two Biden appointees: Lina Khan and Tim Wu.

While attempting to showcase the company’s embrace of progressive economics, Carney largely ignored Sanders’ concern about Amazon’s working conditions.

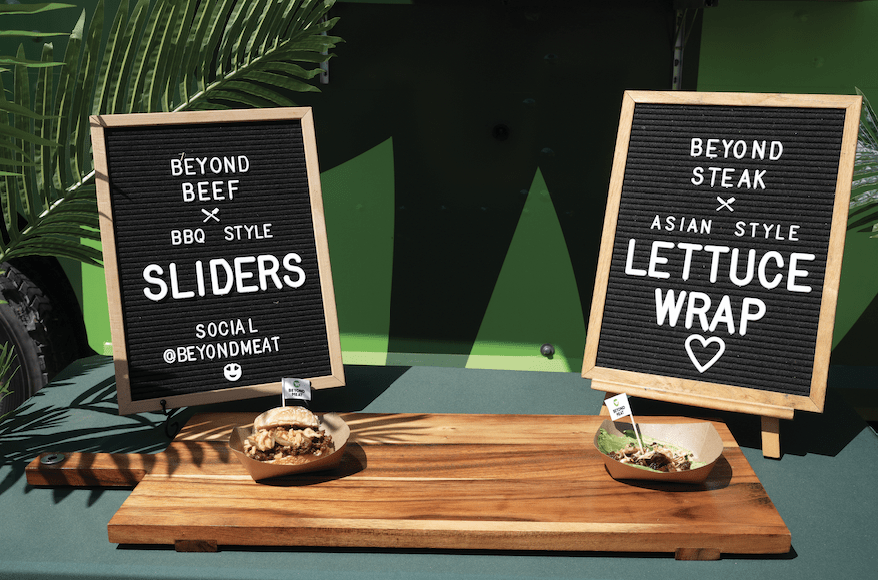

The strategy of shifting the narrative reached new heights when Amazon backed a fledgling trade association called the Chamber of Progress run by Adam Kovacevich, a former senior director of public policy at Google. This tech coalition includes Facebook, Google, DoorDash and Uber. It’s “devoted to a progressive society, economy, workforce and consumer climate.”

The organization says it backs policies that “build a fairer, more inclusive country.” That includes bold action to mitigate climate change, fight income inequality and campaign for progressive taxation.

Why support those causes? Because behind the scenes the Chamber of Progress opposes reform or repeal of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which immunizes websites from liability for third-party content. It also opposed unionization of Amazon’s workforce at its Alabama fulfillment center and resisted classifying Uber and Lyft drivers as employees and providing them healthcare.

In some Washington circles, the Center for Progress’ very existence strikes a note of absurdity. Krystal Ball, a progressive pundit who co-hosts Rising, a web series produced by The Hill, broke out laughing on the air when she announced the group’s mission.

Moments later, liberal Max Alvarez, host of the Working People podcast, characterized the organization as part of the “progress-industrial complex.”

“This is a vicious attempt to co-op something good and repackage it to make more profit and gain more power,” Alvarez said. The association’s commitment to a progressive workforce was laughable, he contended. “These are the companies that destroyed the workforce.”

Big tech companies have “cloaked themselves” in woke ideology, according to Glenn Greenwald, journalist and author. The real motive is to advance their own economic agendas and stifle antitrust efforts, he said.

Policy versus platform

It’s no coincidence that Amazon decided to open its second headquarters (HQ2) in Arlington, Virginia. There, its team can keep an eye on its growing investment in American government. The $2.5 billion campus will be a quick taxi (or helicopter) ride from the nexus of D.C. power.

And if the American people hold the power in D.C., it’s clear that the people don’t care what happens with Amazon. Despite outspoken criticism from think tanks and policy advisors, Amazon thrives, while bending institutions to its will.

Convenience seems to push aside concern for the rights of entrepreneurs and workers. It harkens back to decades of foreign manufacturing and cheap labor practices by large companies—out of sight, out of mind.

In fact, Amazon enjoys a strong public image in some quarters. Republicans regard the military, local police and Amazon as America’s most-trusted institutions, according to a poll by Georgetown and NYU. Democrats listed Amazon as No 1., followed by colleges and universities, and the military. This suggests that widespread boycotts won’t quell Amazon’s power. Actually, the fate of Amazon’s influence may come down to two people: the aforementioned Lina Khan and Tim Wu.

President Biden nominated Khan, one of America’s top antitrust scholars, to lead the Federal Trade Commission. Critics of Big Tech have lauded her famous academic paper, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.”

The paper, which Khan wrote during her time at Yale, reframed “decades of monopoly law,” according to The New York Times.

Khan argued that current antitrust law fails to address the practices of firms like Amazon and instead concentrates on reducing consumer prices. She provides examples, like those mentioned earlier, of Amazon schemes to knock out competition and gain market power.

Khan has served as an aide during Congressional antitrust investigations in tech firms and has received praise from both sides of the aisle. If confirmed for FTC commissioner, she would serve alongside allies inside the White House, such as Tim Wu, another Biden appointee.

Wu serves on the president’s National Economic Council and has warned that today’s monopoly power resembles the excesses of the late 1800s. He is the author of The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age and has apologized for the government’s lax behavior on mergers and acquisitions among tech firms during the Obama administration.

The two-person band of Khan and Wu will face a Goliath in Amazon and its wall of money. They stand as the last line of defense for antitrust opponents before Amazon becomes too big to fail.

Amazon, not satisfied with killing off local stores and traditional retailers, had begun ripping off the vendors on its own platform by the late 2010s, or so complaints to the Federal Trade Commission alleged. Amazon used data gleaned from third-party sellers on its site to launch its own competing brand of staple items, called Amazon Basics—and then gave preference to Amazon Basics in the search results. The FTC complaint alleged Amazon went further yet, tying the prominence of a third-party seller’s products in the Amazon search results to that seller’s purchase of other Amazon services, like its cloud-computing operation, Amazon Web Services (AWS).

Those tactics weren’t new. Amazon was already notorious for forcing its sellers to agree never to offer lower prices at other outlets or on other platforms. Amazon was known to employ ruthless tactics to stamp out online start-ups, especially those offering staple goods. It built its proprietary digital services using parts of open source code from third-party developers. And Amazon famously played hardball in contract negotiations with vendors by slowing delivery of orders to extract pricing and other concessions. The company even allowed counterfeit products to thrive in its store to force sellers like Nike, which preferred to manage distribution itself, to play ball. Even after Nike gave in and offered its shoes on Amazon’s storefront, the counterfeit sales continued. It was simple power politics. Given the size of its audience—almost 40% of online commerce in America moved across its platform—and the reach of its distribution channels, Amazon could single-handedly cripple the companies with which it did business. And it wasn’t afraid to try.

—Excerpted from The Tyranny of Big Tech, Josh Hawley (2021)