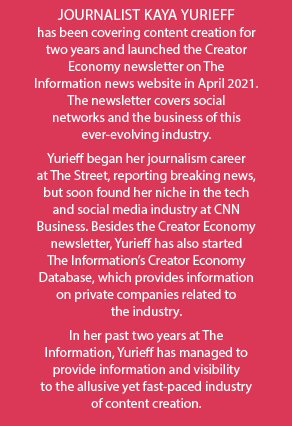

Luckbox Leans in with Kaya Yurieff on the Creator Economy

Luckbox: What’s the dominant story on YouTube and the creator economy?

Kaya Yurieff: YouTube has long been the gold standard for creators when it comes to earning directly from a platform. While creators have made tons of money on Instagram through brand partnerships, they’ve never, until the past two years, really earned much in the way of direct payments from Instagram.

YouTube has the reputation of being the place where you can earn the most money directly from a platform. On top of that, it has also rolled out other ways to make money, such as merchandise, various forms of tipping and paid memberships for YouTube channels. Some creators make a lot of money from that.

Why did TikTok take off the way it did?

TikTok made it quite simple for someone with no preexisting audience to go viral and quickly build a following and garner eyeballs. It became this amazing launching-off point for people who want to be a creator.

As YouTube and Instagram became saturated, it became harder to reach a threshold of 1 million followers on YouTube. On TikTok, people are reaching these milestones left and right.

YouTube always had a higher barrier to entry. While the very first video uploaded to YouTube was a low-quality short film called Me at the zoo, over time, YouTubers really needed lights and a nice camera. When you are making longer videos, a lot more goes into that. With TikTok, you just need your cell phone. You can film it in your messy bedroom. It is more authentic. You have the editing tools within TikTok, and you are off to the races.

How did YouTube react to the emergence of TikTok?

YouTube had to adapt. So that’s where YouTube Shorts came in. Every platform had its lane—Instagram was photos. YouTube was longer-formatted video, Twitter was short-form text. And then suddenly, everyone is interested in short-form video because of TikTok.

How do creators feel about YouTube Shorts and TikTok? Which provides a greater

financial opportunity?

I think TikTok has captured the cultural zeitgeist, which is important. Yes, people are also posting short videos on Instagram Reels and Snapchat. But the trends are starting on TikTok. Even big platforms and deep pockets have not been able to unseat TikTok in the same way Instagram stories were able to stunt Snapchat’s growth.

It is interesting to see how creators are using TikTok. Some short-form video creators are focusing on Shorts, whereas the longer-form creators are using Shorts to bring people to their YouTube channel to watch their longer videos. So, it has become, for some creators, complementary. I still think TikTok’s algorithm is unmatched in the manner of how well it serves its users.

At the same time, it’s arguably the case that the bonds creators and their audiences form are lesser on TikTok than on YouTube.

In a post TikTok world—which we’ll have if legislators move ahead with a U.S. ban—what does the market look like?

Yeah, I do not think short-form video goes away. TikTok has certainly done something to our attention spans where we like this idea of bite-size content.

What about Spotify? Is it moving into video and podcasts?

They’ve made a big push into podcasts. I think a lot of creators do enjoy it. But many creators do not want to be on the hamster wheel of having to create a YouTube video or a TikTok 15 times a day or three times a week. So sometimes different outlets, like a podcast, can just be a new kind of creative opportunity.

We have seen Spotify lean into exclusive deals. The Emma Chamberlain podcast is available only on Spotify. But the platform also built out a robust set of tools for all sorts of creators. They did this big redesign to their home feed. So that is making things more visual.

Follower counts mean something different on TikTok than YouTube, correct?

Yes. TikTok changed the meaning of follower counts, right? A million followers on YouTube was a big deal, and they would send you plaques when you hit certain milestones. But with TikTok people reach that milestone in 30 days instead of the nine years it took on YouTube.

So, those can be useful to measure, but do we consider it a breakout if a person grew by this amount in 30 days? It’s harder to measure their cultural impact.

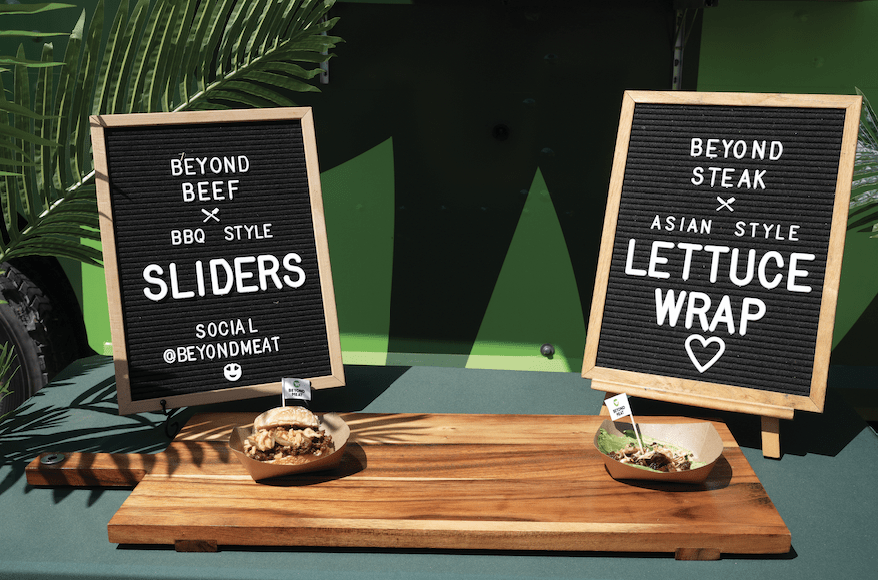

Many creators have crossed over into business. A good example is MrBeast, who launched the Feastables snack-food line. What are some other examples of how people have monetized their creator fame?

There are so many ways. For a lot of YouTubers, [Google] AdSense used to be a big part of their income and now it’s like a quarter of it because they’ve diversified. It’s hard to get these numbers, but academics and think tanks are researching this.

I speak with creators every week and a lot of them started out relying on AdSense and then, after seeing the fluctuations in revenue, wanting to diversify their businesses. Forming brand partnerships is the No. 1 way creators make money, even on YouTube.

Some creators sell their own products. Emma Chamberlain has Chamberlain Coffee, and that is a brand she owns. Same thing with MrBeast with Feastables. David Dobrik opened a pizza restaurant in Los Angeles last year. Lauren Ireland and Marianna Hewitt are two beauty influencers who started the company called Summer Fridays.

Does YouTube get a cut of the brand partnership revenue or does it go directly to the creator?

That is direct to the creator.

Is a bubble is forming in the creator economy?

It’s a new form of entrepreneurship that will not go away. But I also think there’s so much content that it’s harder and harder to break through. You have to figure out a way to differentiate.

We had a lot of casual creators accidentally stumble into this because of TikTok—and even TikTok is reaching a saturation point.