Less Than Electrifying

Range worries and sticker shock are slowing the growth of EV sales

Filled with optimism, American and European automakers were plunging headlong into electric vehicle production just a year ago. So, why are they pulling back?

“There was one component missing in the forecasts of the EV transition and that was demand,” said Steve LeVine, an automotive journalist at The Information, a digital news outlet.

Shoppers “very likely” to consider buying an EV fell to 25.6% in January, a percentage point lower than in December, according to J.D. Power, a firm known for car reliability ratings.

EV sales in North America are expected to grow this year by 25% to 30%, but that’s down from 46% last year, multiple sources agreed. It’s a big enough slowdown to pit Tesla (TSLA) against General Motors (GM) in a price war and force Ford (F) to cut back production of its F-150 Lightning EV.

Meanwhile, reports from the front lines of auto retailing shed light on why growth has slowed.

EVs gathering dust

“As people come into the store to look to buy transportation, they are identifying the EVs as more expensive and less useful,” said Mickey Anderson, CEO of Baxter Auto Group, an Omaha, Nebraska-based network of 21 dealerships selling nine car brands in four states. “Far more often than not, they’re not the right choice for customers today.”

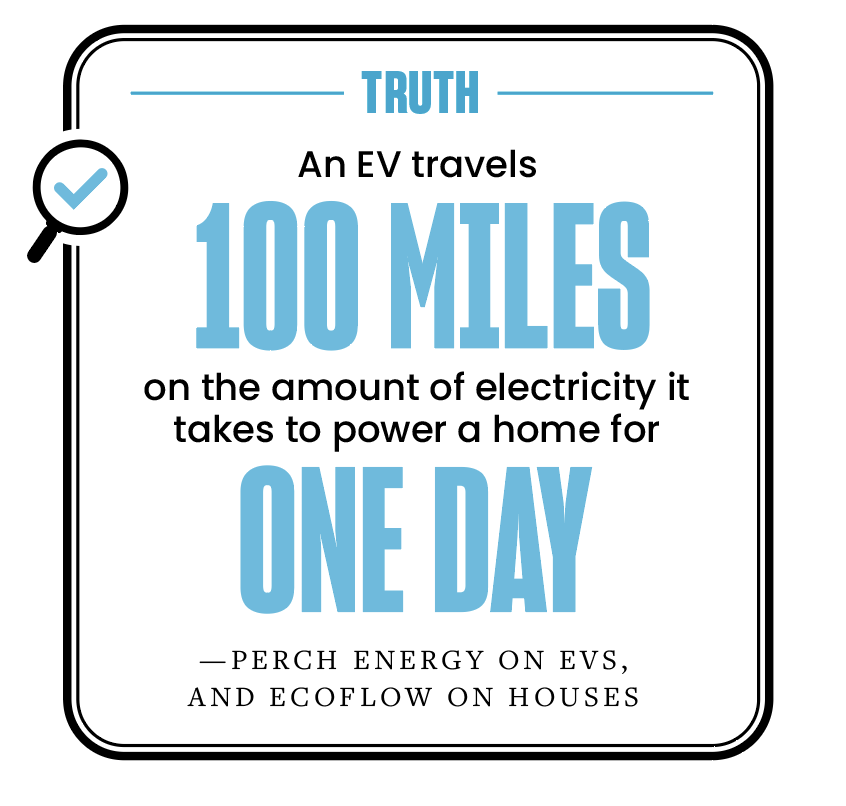

Many of his potential buyers drive long distances across the Great Plains and in the Midwest, making them skeptical of owning a vehicle that might travel only 150 miles on a charge. What’s more, the region’s bitterly cold winters challenge the capacity of car batteries.

Motorists often fear they’ll find themselves far from a charger when they need to power up. Some also object to waiting 20 minutes or so for a car to charge on a public device at the end of a dark and lonely Walmart parking lot.

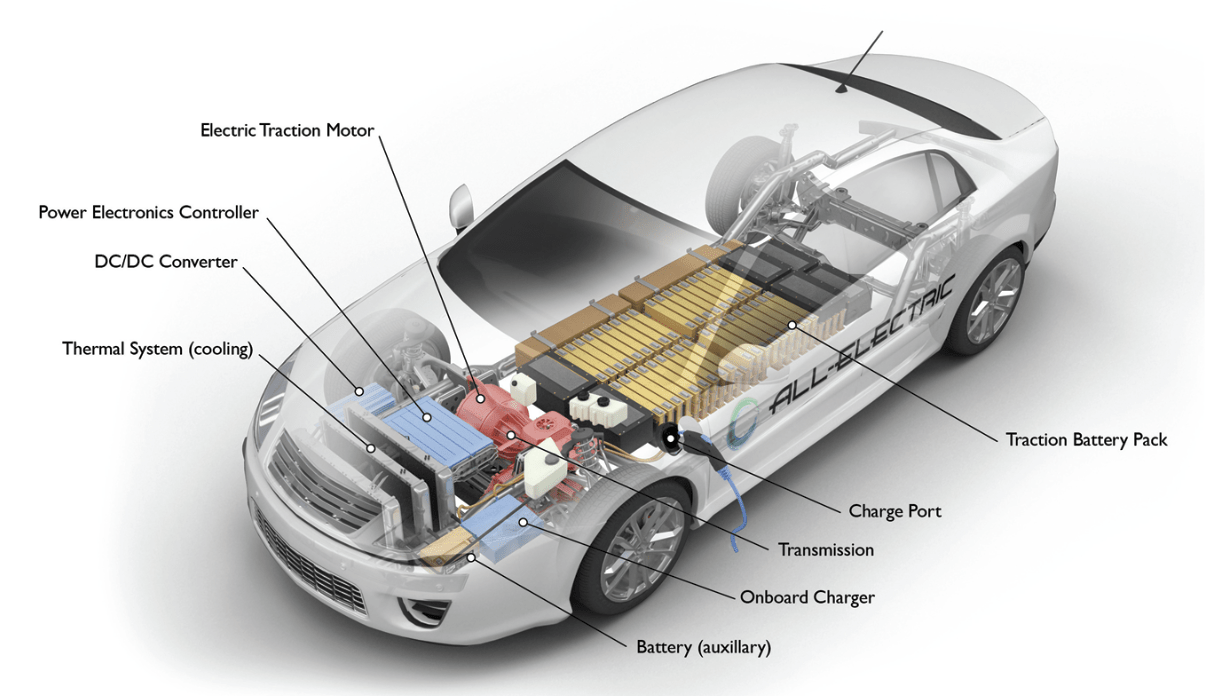

Then there’s price. The average EV sticker price of $60,000 is about $10,000 more than the typical car with an internal combustion engine, or ICE, according to automotive writer and broadcaster John McElroy.

Price wasn’t a big enough factor to discourage the tech fans and status seekers who became the early adopters of EVs, but it compels average consumers to stick with less-expensive ICE vehicles.

These days, however, the price differential is continuing to narrow and may disappear in two to three years, LeVine said. That’s when the true demand for electric vehicles will come into focus.

“If they still aren’t buying EVs, that means there’s something wrong,” he said of the near future when EVs and ICE vehicles reach price parity.

But whether they like EVs or not, consumers should choose their means of locomotion for themselves without the federal government deciding for them, Anderson maintained. In his view, free markets should prevail, not policy makers.

Freedom to choose

“If carbon were cancer, we would never dream to let the federal government mandate one therapy to fight it,” he said. “This is the one drug, and 75% of that drug is made by the Chinese.”

Without intervention, the public would choose a mix of vehicles powered by a wide range of sources, including batteries, gasoline, diesel, hydrogen and biofuels, Anderson said.

Instead, the Environmental Protection Agency is easing but not abandoning emissions standards and mileage requirements that would push automakers to phase out ICE vehicles.

To comply with the regulations, manufacturers would need to ensure that by 2032 about two-thirds of the cars they produce are electric, said Nick Nigro, founder of Atlas Public Policy, a company that helps businesses and state and federal agencies track issues.

The declining cost of building EVs could encourage car makers to exceed the EPA standards because it would be in the best interest of their businesses, Nigro suggested.

But those standards still amount to a de facto EV mandate, and that prompted Anderson to become part of an informal alliance representing 4,000 dealerships. The ad hoc group has dispatched two letters to the Biden administration asking it to “tap the brakes” on promoting EVs.

Unrealistic EV goals?

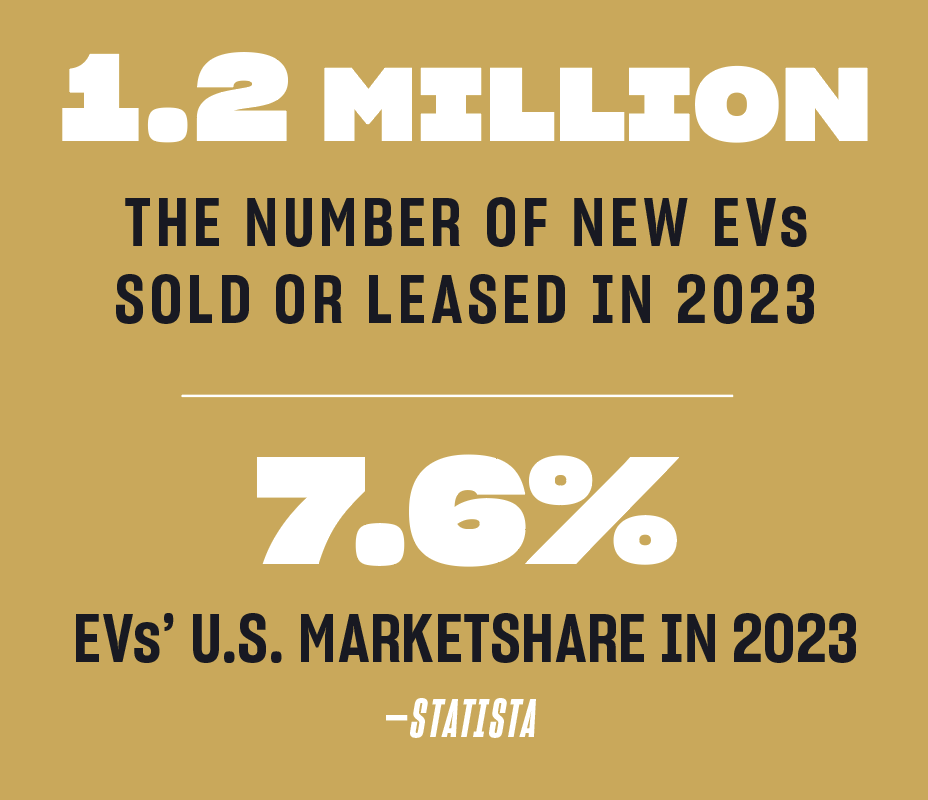

Growing EVs’ market share from 7.6% in 2023 to 67% in nine years simply won’t work, the dealers maintained in the letters. Reaching the government’s goal of having 2.8 million public chargers by 2032, up from 170,000 today, would require building 800 every single day and in their opinion strains the imagination.

Besides, EV production can be anything but green, Anderson noted. “I’m a car dealer in Omaha, Nebraska, and even I’m aware of what’s going on in the strip mining of Malaysian rainforests to get nickel and the really irresponsible way that they’re chasing down rare earth minerals in the Congo,” he said.

But green or not, EVs have been receiving government largesse for years in the form of loans, tax credits, research grants and funding for charging stations. Some might conclude it’s already too late to stand aside and allow the markets to reign.

EV buyers can qualify for a tax credit of up to $7,500 on new or used EVs, depending upon the purchaser’s income, the price of the vehicle, and where the car, battery, minerals, and other components were sourced or manufactured.

Lately, attention has focused on the slow rollout of a federally funded network of EV chargers 50 miles apart along the nation’s major highways. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that President Biden signed in 2021 provides $7.5 billion to subsidize placing 500,000 of the chargers by 2030.

When LeVine began tracking research on EV batteries in 2010, researchers “cherished” grants in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. “If you were a researcher or a company and got a three-year grant for $2 million or $3 million, you’d take your wife out to dinner—that was an incredible amount of money,” he said of conditions 14 years ago. “And now they routinely give $100 million to one company to do something.”

The Obama administration committed $2.4 billion to building the EV battery supply chain, he noted, and the government loaned Tesla $465 million to fund development of the Model S.

No one knows how much cash the government may eventually spend promoting EVs because it depends upon how much the public avails itself of the incentives and how businesses react to charger subsidies, LeVine said. But some observers expect a $500 billion price tag, and others warn it could easily reach $1 trillion, he notes.

Still, some consider it money well-spent.

Seizing the EV future

“The U.S. has to try to win the future here,” said Nigro. “We’re playing catch up, unfortunately, because we were asleep at the wheel for about four years, between 2016 and 2021. And in that time period, Europe and China passed us in terms of leadership on this issue.”

But the future need not resemble the past. The ingenuity that put America on wheels could keep it on wheels in a new era of electrification.