Trading Time

Timebank members exchange an hour of their work for an hour of someone else’s

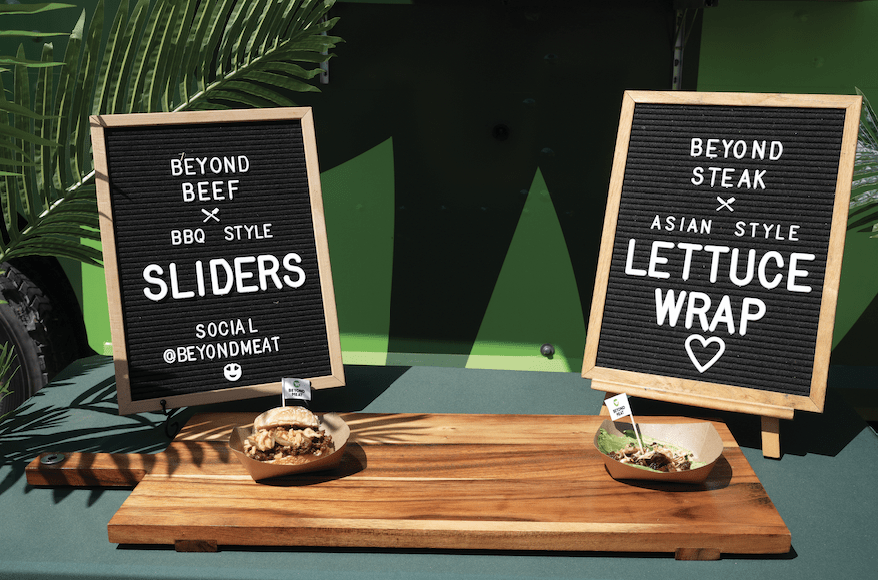

An enthusiastic gardener who hates to bake might be a perfect candidate for “timebanking,” an international movement whose members swap time and skill instead of shelling out cash for what they need.

For every hour timebankers spend performing a service, they’re eligible to receive an hour of work in return from another member. Everyone’s time has equal value in the eyes of the organization, whether it’s spent patching a leaky roof or raking autumn leaves.

Exchanging labor beats volunteering because it strengthens self-worth by making members feel their time has value, says Christine Gray, one of the founders of timebanking.

“Getting things for free can actually undermine your sense of capacity,” Gray maintains. Members of timebanking organizations don’t feel they’re getting handouts, even though they’re not paying for goods and services, she says.

Origin story

Gray helped create timebanking with her late husband, Edgar S. Cahn, a law professor, speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy and co-founder of the Antioch School of Law. They described the idea in an article published in the 1980s by the Stanford Social Innovation Review, a magazine and website.

The couple went on to start TimeBanks USA, which has now become TimeBanks.Org. It’s active in more than 400 communities across the country, and more than 20 additional sites are in the works.

Local organizations operate autonomously, making some of their own rules and setting many of their own policies, says BJ Andryusky, founder of one of those local groups, the St. Pete Timebanks in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Calculating the value of the work performed by members at $29.95 an hour, timebanking has contributed at least $104.6 million to the economy. But members emphasize that the accounting is loose and thus greatly undervalues the group’s contribution.

Timebankers view their movement as neither bartering nor volunteering. Instead, they think of it as an entity that produces a non-taxable currency called “time credits.”

How it works

Let’s share the adventures of some imaginary characters to get a better understanding of timebanking.

Suppose Abby, an avid gardener, joins a local timebank. Another member, Greg, needs help planting tulips in his backyard. Abby works with Greg for one hour and logs one time credit into her timebank account, which removes one time credit from Greg’s account.

A little later, Abby needs help putting up a fence post. Maria spends two hours helping Abby with the fence and logs two time credits, which come from Abby’s account.

Next, Maria decides she wants to use Mason jars to make candles. Frank has plenty of them, and the two agree 12 jars equal one time credit. Maria spends one time credit to obtain a dozen jars, and Frank gains one when he hands over the jars.

All things (un)equal

Every time credit has the same worth, regardless of the task performed—a proposition that stumps some economists, Andryusky notes. It means the labor of a high-school student who bags groceries is an even trade for the work of a skilled tax preparer.

With “real world” currency, it doesn’t work that way. A skilled tax preparer makes $30 an hour, while someone grilling burgers in a fast-food joint might barely make minimum wage.

“Societal value is what separates income,” Andryusky says, “And we don’t live in an egalitarian society.”

But time credits mean more than the everyday type of money everyone always exchanges, according to Gray. She quotes a beer ad from the 1970s to make her point.

“Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach,” she says. That parallels the notion that time credits have more dimensions than mere dollars and cents can provide. “This currency reaches the parts that other currencies can’t,” she says.

Besides promoting self-worth, timebanking makes a formidable contribution to communities, as noted on hOurworld (not a typo), a platform that logs timebanking hours across the world. Nearly 3.5 million hours had been exchanged when Luckbox went to press.

But the actual number of hours traded is probably much greater. “People use the software and then they get sort of lazy about it,” Gray says. “They continue to exchange, but it doesn’t matter because it’s about the premise behind it.”

Day-to-day ops

The finances vary among local timebanking operations. St. Pete Timebank, for example, received a grant for 2020 that provided $5,000 for software, $2,500 to cover liability insurance and $4,000 to bankroll leadership training, among many other expenses, Andryusky says.

Each timebank operates on its own, down to the point of deciding how to capitalize timebank, Timebank or TimeBank. Some use software from TimeBanks.Org called Community Weaver, which costs between $1,200 to $5,000, depending on the year, while other local organizations rely on hOurworld software.

With either software provider, users can log time credits and post proposed exchanges. Both sets of software differentiate between the all-important timebanking ideas of giving and receiving.

Differences among local organizations don’t end with the software. Because they’re autonomous, some charge membership fees and others don’t. Avoiding that fee can force them to solicit donations—just to keep the lights turned on.

Gray summarizes the necessity of finding funding this way: “How does the airplane keep flying without any fuel?”

Growth, decline, growth

One of the nation’s largest timebanks, Crooked River Alliance of TimeBanks in Kent, Ohio, relies on donations, says Heather Waltz, who serves as chair. But in a world where money and culture intertwine, even timebanks aren’t sustainable without cash.

“Membership to our timebank is free for all,” Waltz says, “but we ask anyone who is willing to, to donate towards our costs. This and our fundraisers allow us to continue to make the timebank free.”

Local timebanks and TimeBanks.Org rely on boards of directors who earn time credits for their administrative work.

Timebanking has been around nearly 40 years but has never grown as quickly as Gray and Cahn had hoped.

In 1992, the movement bloomed but then crashed. “There were thousands of people wanting to start up timebanks,” Gray says of those days.

Gray and Cahn went international with timebanking in 1998, spurring what Gray dubbed a renaissance. The phenomenon quickly gained momentum in the United Kingdom.

Later, she began telephoning timebankers on a list of about 100 timebanks. “I called everyone on the list and about 30 responded,” she remembers. “Some of them were very healthy and some were struggling.”

Now, timebanking is surging again. Twenty-three new local organizations are pending timebanks in cities ranging from San Diego to Philadelphia to Gary, Indiana. As timebanks grow, local economies flourish, promoters say.

“Everyone can benefit from a timebank,” Andyrusky concludes. “It just depends on whether you value your time enough to join.”