Buy the Dip (Or Don’t?)—Indices vs. Single Stocks

"Buy the dip" refers to a trading/investing approach that involves purchasing an asset, or group of assets, after a drop in price.

“Buying the dip” may not be the most sophisticated strategy on Wall Street, but it’s certainly been a strong performer. That held true again last week when the stock market ripped higher after a sharp correction on Sept. 20.

Buy the dip refers to a trading/investing approach that involves purchasing an asset, or group of assets, after a drop in price. For example, if a trader/investor liked Apple (AAPL) at $150/share, wouldn’t he or she like it even more if it dropped to $130/share?

Of course, the ultimate attractiveness of a security after a drop in price lies in the eye of the beholder, but this example at least helps illustrate the mechanics behind buying the dip.

While the approach has been around for a long time, buying the dip gained newfound fame in 2020 when the stock market snapped back from a sharp correction catalyzed by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since then, buying the dip has seemingly gained even more traction in the markets as more and more market participants have jumped on board.

After dipping as low as 4,305 on Sept. 20, the S&P 500 has now rallied over 150 points, and is trading only 1.7% below its all-time closing high of 4,536. As a result, those that bought the most recent dip in the S&P 500 have clearly benefited.

However, when broadening the lens to include a wider range of underlyings, the picture isn’t quite so rosy. For example, those market participants that have been buying the dip during the recent rout in Chinese stocks haven’t seen the same degree of success—not by a long shot.

Looking at Alibaba (BABA), that particular stock is currently trading just shy of its 52-week low—$145.08/share as of Sept. 24. That means investors and traders that bought BABA after it initially dipped back in October 2020 have been along for quite the ride—the stock has dropped from roughly $300/share all the way down to its current levels below $150/share.

This example proves that while buying the dip has worked in some instances, it’s been a disaster in others.

The only hope for investors and traders of BABA is that they were “dollar-cost averaging,” which is a close cousin of buying the dip, as it relates to investing/trading approaches.

Dollar-cost averaging refers to the practice of systematically investing into a security or asset over a period of time—regardless of price. So an investor looking to deploy $100,000 into a given stock might start with $20,000, and then deploy an additional $20,000 four more times over the course of the next several weeks or months to complete the full $100,000 investment.

This could be executed at regular intervals—once a month or once a quarter, for example—or at irregular intervals, depending on the vision of the investor/trader in question.

Considering that securities tend to fluctuate in value over time, one can see how dollar-cost averaging would reduce the overall impact of volatility on the price of the target asset. Because the price paid for the security will vary each time a periodic investment is made.

Looking at the last 10 months of trading in BABA, one can see how a dollar-cost averaging approach might have benefited an investor/trader, as opposed to investing the full amount upfront. In the latter case, an investor deploying their complete investment into Alibaba in October 2020 would be down roughly 50% on that investment.

Of course, an investor dollar-cost investing into BABA since last October would likewise be down on his/her investment, but not so severely.

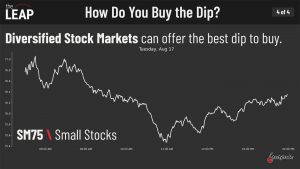

Circling back to buying the dip, that suggests that traders looking to reduce concentration risk might be well-advised to buy the dip in diversified underlyings—like the S&P 500, or another index.

Buying the dips in the S&P 500 since last October would have been a winning strategy because the S&P 500 is currently trading higher than it was at that time—approximately 30% higher.

As noted previously, BABA is currently trading about 52% lower than it was in October of 2020—suggesting that dip buyers in this security have been far less fortunate.

It’s important to note that BABA dip buyers may ultimately end up on the winning side of this trade, especially if they weren’t buying dips using leverage and were able to withstand the capital drawdowns associated with an extended losing position.

The current rout in Chinese stocks has undoubtedly pulled in a bevy of fresh contrarians hoping to net big returns on a snapback—and some of them are undoubtedly traditional dip buyers.

To learn more about this approach to trading and investing, readers are encouraged to review a new episode of The Leap: From Options to Futures on the tastytrade financial network. This episode focuses on the potential benefits of using diversified underlyings (like indices and ETFs) to buy dips, as opposed to single stocks.

More information on this topic is also available on this new installment of Small Stakes. For updates on everything moving the markets, readers can also tune into TASTYTRADE LIVE—weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CST—at their convenience.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.