Does “Tail Risk Protection” Pay?

Investors and traders that owned tail risk protection in spring of 2020 likely benefited from that foresight, but the long-term maintenance costs of such protection is significant.

Tail risk in the market refers to a form of portfolio risk which captures the remote probability that the value of a given investment could move by more than three standard deviations from its current value.

As a portfolio risk management concept, tail risk is somewhat related to “black swans.” Black swans are loosely defined as unexpected events that have a dramatically negative impact on the financial markets.

Importantly, the difference between tail risk and a black swan is that the latter typically engulfs the entirety of the markets, whereas tail risk can speak to the risk associated with a single position, or a portfolio of positions.

In that regard, all black swans involve tail risk, but not all tail risk involves a black swan.

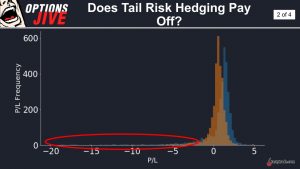

Visualizing a “normal” bell curve of investment returns, tail risk is captured in the extreme ends of the curve—extremely low probability scenarios—as illustrated in the chart below.

When crude oil traded in negative territory for the first time in history during 2020, that was the perfect example of tail risk. Crude oil futures had never before traded in negative territory, so that’s not something many market participants would have planned for.

In broader terms, however, crude oil got caught up in the black swan represented by the global COVID-19 pandemic, which catalyzed a cratering in crude oil demand. With global suppliers unable to quickly reign in production, the world was awash in crude, and futures prices reacted accordingly by dropping below zero.

Because of last year’s coronavirus-induced market correction, even investors and traders that are relatively new to the market are well aware of the tail risk concept. A pertinent question, therefore, is whether market participants can protect themselves from future events involving tail risk?

This precise risk management-related topic was recently addressed on fresh installment of Options Jive on the tastytrade financial network.

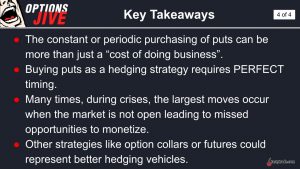

As discussed on that show, the most common approach that investors and traders use to protect against tail risk is to purchase out-of-the-money (OTM) puts. These puts represent a form of insurance in case the market drops, much like auto insurance covers accidents and hurricane insurance covers storm damage.

While owning such puts may sound like a good idea, one can’t overlook the fact that huge corrections in the market aren’t that common.

Going back to 1946, there have only been 12 major stock market corrections in U.S. history, including the one from 2020.

The 12 major market corrections of more than 20% in U.S. stock market history are listed below (month/year of market bottom and percent decline).

- May 1946 (-21%)

- June 1948 (-20%)

- October 1957 (-21%)

- June 1962 (-28%)

- October 1966 (-22%)

- May 1970 (-36%)

- October 1974 (-48%)

- August 1982 (-27%)

- December 1987 (-33%)

- October 2002 (-49%)

- March 2009 (-57%)

- March 2020 (-34%)

As one can see in the above data, major corrections don’t usually occur in quick succession of one another. But of course, that doesn’t mean a significant market correction can ever be ruled out completely.

The above does help illustrate the fact that buying OTM puts to protect against market-wide corrections represents an expensive endeavor, at least at the broad-market level. An investor continuously purchasing protective OTM puts since the conclusion of the Financial Crisis in 2009 would have burned a lot of capital leading up to the bear market correction in 2020.

This example suggests that buying tail risk protection is most effective when market participants can time it such that the insurance actually covers a severe correction. That’s no easy task.

Alternatively, it’s possible some market participants may want to try and use puts to protect themselves against tail risk in specific positions, as opposed to market-wide events. For example, cryptocurrency investors owning OTM puts in Bitcoin would have benefited greatly from that insurance during the most recent crypto meltdown.

The use of such protection, against specific positions, will likely vary by investor/trader, depending on one’s unique outlook and risk profile.

To learn more about the cost-benefit analysis of tail risk protection, readers are encouraged to review the aforementioned episode of Options Jive on the tastytrade financial network when timing allows.

Additionally, readers may want to review this tastytrade programming, which focuses on defending against outsized moves.

For updates on everything moving the markets, readers can also tune into TASTYTRADE LIVE—weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CST—at their convenience.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.