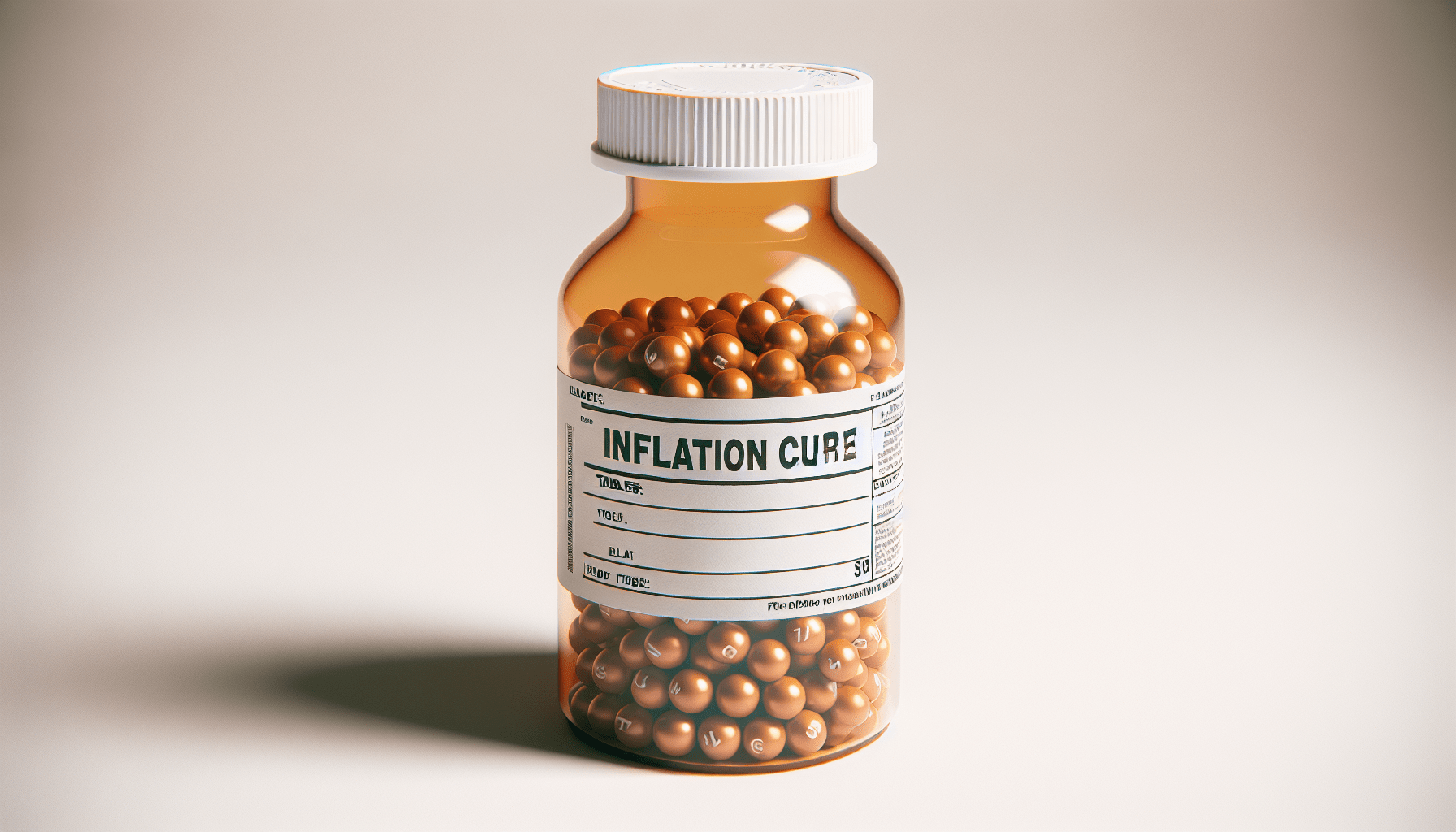

No, It’s Not Stagflation

Yes, prices are up and GDP is down compared with earlier this year, but the economy isn’t entering a ’70s-style malaise

The economic woes of the 1970s, a decade marked by runaway inflation and painfully slow growth of gross domestic product, came to be known as stagflation. Could a similar fate befall America in the near future? In this article, a currency expert says he doesn’t foresee a return to those conditions—at least not yet. A story that begins on p. 20 presents a different view.

The U.S. economy seems to have fallen into a bit of a quagmire. Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) or the Fed’s preferred gauge of inflation, the personal consumption expenditure index (PCE), is running at its highest level in 30

years. Meanwhile, growth rates appear to be sagging.

The Q3 report on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) showed a +2% annualized real growth rate. The sharp slowdown comes after two strong quarters to

start the year, with Q1 and Q2 U.S. real GDP coming in at +6.5% and +6.3% annualized, respectively.

Some commentators and market observers are suggesting the slowdown in

the third quarter marks the onset of

stagflation, defined as “persistent high inflation combined with high unemployment and stagnant demand in a

country’s economy.”

The state of the economy, so they say, could be creating a policy dilemma that would push the Federal Reserve into a corner as it prepares to taper asset purchases and ultimately raise interest rates. And with President Joe Biden’s fiscal stimulus plans mired in Congress, thanks to divisions between progressives in the House and centrists in the Senate, the threat of a fiscal cliff—a sudden drop in government spending—looms large as a potential albatross around growth’s neck in 2022.

However, ample evidence suggests this isn’t your father’s stagflation. In fact, it may not be stagflation at all. Indeed, price pressures are high, the highest seen in decades. But the other conditions of stagflation haven’t been met. In fact, quite the opposite is true.

Consider the labor market. The unemployment rate (U3) is back below 5%, and while job gains have been inconsistent in recent months, the pre-pandemic labor force is returning more quickly than after other downturns in the post-World War II era.

About 18 months after the start of the pandemic, the economy is still approximately 3.5% below its peak employment in 2020. After the global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008, it took approximately 50 months before the economy was only 3.5% below its pre-recession peak employment. It ultimately required 78 months to recover all of the lost jobs. The labor market is recovering jobs at a breakneck pace, considering the pandemic provoked the largest drop in employment in economic history. So, the labor market isn’t suffering from stagflation.

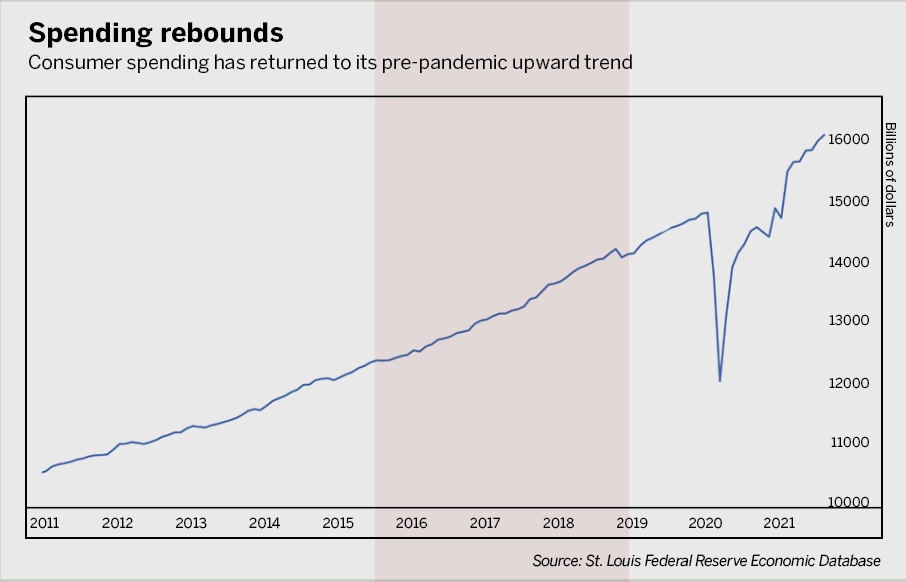

The case for calling the current situation stagflation becomes even weaker when one considers the demand side of the equation. Personal consumption expenditures are at their highest level ever and, according to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s economic database, consumption is actually above its pre-crisis trend.

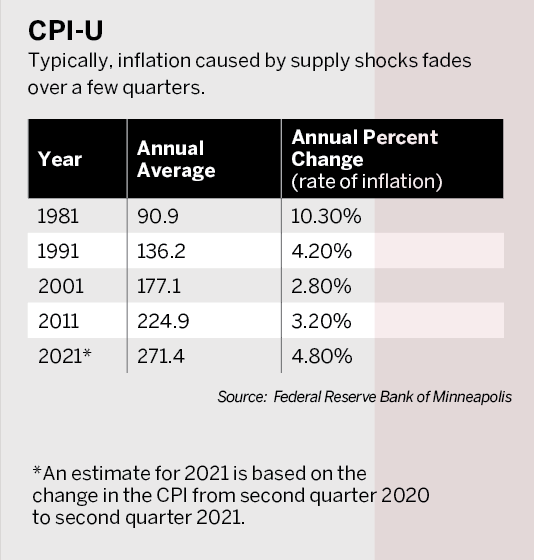

The inflation Americans are experiencing comes from strong demand amid a supply shock to supply chains left in disarray by the pandemic. Plus, the economy has history on its side. Typically, inflation caused by supply shocks fades over a few quarters.

Sure, the economy is experiencing slower real GDP growth now than earlier in the year. But the labor market is proving resilient, if not strong, and consumers—many with the assistance of government financial support during the pandemic—are spending more money than ever.

Will backlogged ports create more problems in the short term for businesses and consumers? Most likely. But the economy isn’t facing stagflation. It’s an economic boom limited by supply constraints that should fade in 2022 and beyond.

Christopher Vecchio, a senior currency strategist for DailyFX, forecasts economic trends in a number of countries. @cvecchiofx