Dollar Dominance: If BRICS Currency Plan Comes to Fruition, the Dollar Could Get Dinged

The U.S. dollar has dominated as the world’s number one reserve currency since the end of WWII, but the proposed BRICS currency could mount a legitimate challenge to dollar hegemony.

World War II laid waste not only to the world’s physical landscape, but also to the geopolitical pecking order. The United States was one of the biggest beneficiaries of that upheaval, as was the U.S. dollar.

In the wake of World War II, the Allied Alliance—delegates from forty-four nations—implemented the Bretton Woods system, which stipulated that all national currencies were to be valued in relation to the U.S. dollar, and that the dollar in turn would be convertible into gold at a fixed rate.

This treaty, above all else, was responsible for elevating the U.S. dollar to its current status as the world’s number one reserve currency.

On top of that, the rising power of the U.S. manufacturing sector likewise boosted the dollar’s global profile, as foreign companies were forced to convert their own currencies into dollars in order to procure goods from the U.S.

Then, in 1973, the U.S. made a deal with Saudi Arabia, which further cemented the dollar’s lofty position in the global financial system. In exchange for promises of military protection, Saudi Arabia agreed to sell its oil in dollar terms—no matter the trading partner.

The rest, as they say, is history—after displacing the British pound, the U.S. dollar has dominated as the world’s top reserve currency for nearly 80 years now.

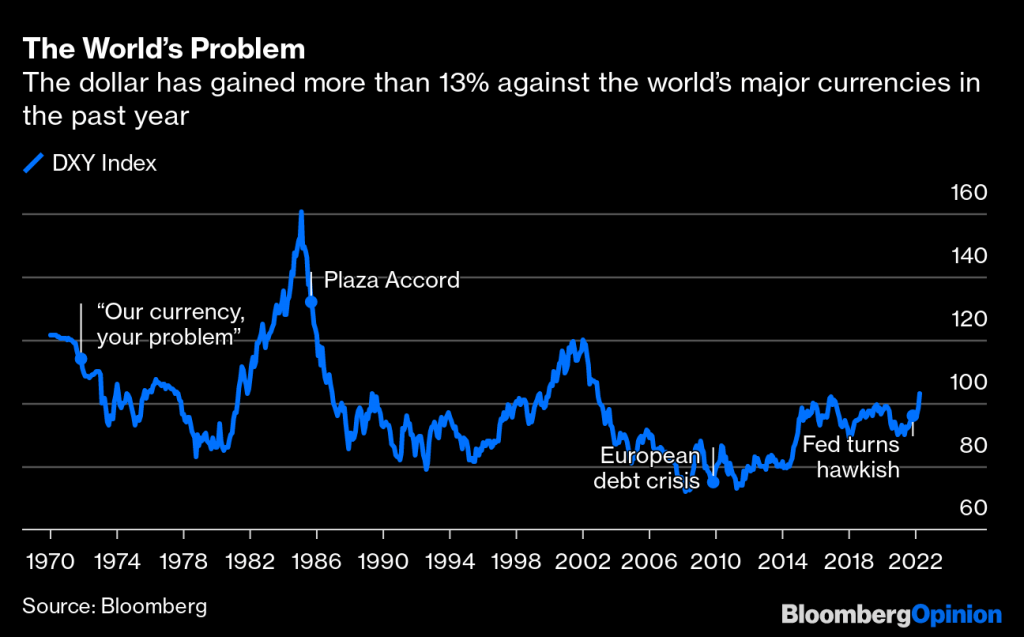

And as illustrated by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the dollar remains a key haven for investors, traders and everyday citizens during periods of economic uncertainty. The dollar surged in value during 2021 and 2022 as the world economy grappled with the impact of the pandemic.

However, nothing lasts forever, and based on recent reports, the dollar’s role in the world economy could soon weaken.

Later this summer, a group of countries widely known as the “BRICS” (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) is expected to announce a new currency that’s designed to challenge the dollar’s position as the number one reserve currency in the world.

The proposed BRICS currency

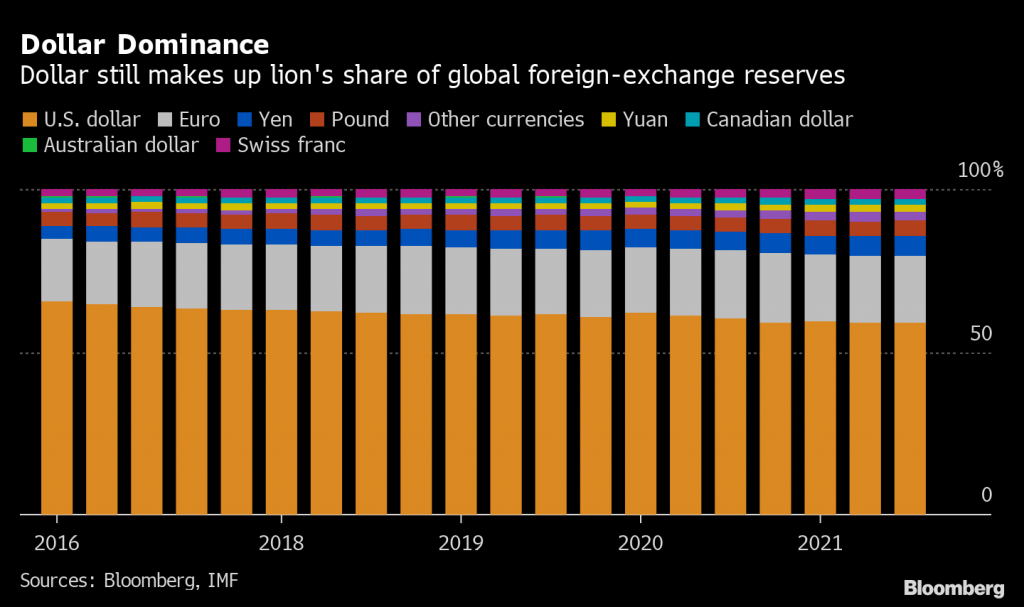

Today, about 59% of the foreign reserves held by global central banks are denominated in USD. Moreover, roughly half of all international trade is currently invoiced in dollars.

While those figures are certainly impressive, they have weakened in recent years. Twenty years ago, the dollar accounted for about 80% of the world’s foreign reserves.

The U.S. has lost market share because some countries—particularly China and Russia—have been working to circumvent the dollar, as both a reserve currency and a medium of cross-border exchange.

For example, in 2021, Russia reduced the percentage of its reserves held in dollars from 24% to 21%. Several years before that, Russia had slashed its holdings of U.S. Treasury securities.

On top of that, China and Russia have increased use of their own currencies for bilateral trade. As of April 2023, 70% of the bilateral trade between China and Russia was denominated in rubles and yuan, as compared to only 30% two years ago.

China and Russia have long criticized the dollar’s outsized role in the international financial system, and have been especially negative on the greenback since the U.S. and Europe froze roughly $300 billion of Russia’s reserves when it sanctioned the country for invading Ukraine.

In order to reduce the dollar’s role in the international financial system, the two countries have been pressuring their trading partners to use anything but the dollar for settling cross-border transactions. Along those lines, Brazil and China recently agreed to settle trade between the two countries in their own currencies, cutting out the dollar as an intermediary.

But the challenge to greenback doesn’t stop there.

Back in October of 2022, reports circulated that the conglomerate of countries known as the BRICS were considering launching a new reserve currency, and more details on that effort are expected to be announced at the group’s upcoming summit on August 22.

At this time, it’s expected the new BRICS currency would be used to settle cross-border payments within the group, as opposed to replacing the sovereign currencies of the BRICS within their own respective economies. Other countries, such as Argentina, Mexico and Saudi Arabia, have already indicated an interest in joining the new currency bloc, if it materializes.

Together, the BRICS constitute roughly 32% of global GDP, and more than 40% of the world’s total population. They also hold upwards of $5 trillion in foreign reserves.

In that regard, the successful launch and implementation of the proposed BRICS currency could represent a real threat to dollar hegemony.

A stiffer challenge than the euro or yuan

For many years, pundits have predicted the demise of the dollar as the world’s preeminent global currency.

And while the dollar has lost some market share in the last twenty years, it remains firmly entrenched as the reserve currency of choice among global central bankers.

However, the reason the dollar has held firm is arguably due to the fact that there hasn’t been a legitimate challenger.

The euro has been around since 1999 and, so far, hasn’t managed to steal the dollar’s thunder. It’s not expected to do so anytime soon, either.

Some also predicted that the Chinese yuan would eventually threaten the dollar’s dominant position, but those projections haven’t come to fruition. Today the Chinese yuan only constitutes about 3% of global foreign reserves—significantly less than the euro.

One of the biggest complications with the yuan relates to its convertibility. Convertible currencies are those that can be easily bought and sold on the foreign exchange market with few restrictions, if any.

Trading of the yuan is limited to mainland China and Hong Kong. The dollar, on the other hand, is freely traded worldwide and easily convertible. Moreover, the People’s Bank of China sets a daily reference rate for the yuan against the dollar, from which interbank trading markets cannot diverge from by more than 2 percent.

As a result, it’s estimated that roughly 90% of foreign exchange transactions in 2022 involved the dollar. That’s because most foreign currencies are converted to the dollar, and then converted to another foreign currency—as opposed to being converted directly between the two.

In addition to convertibility, the U.S. dollar also ticks many of the other boxes that characterize an attractive reserve currency, including: a stable political system, a large economy, a globally integrated economy, a credible legal system, high-quality sovereign debt and deep/liquid financial markets.

Considering this background, it’s fairly clear why the dollar hasn’t faced any real threats as the world’s top reserve currency to date. But it also provides the context for why a widely-supported BRICS currency might be able to mount a more realistic challenge.

Several reports have indicated that the BRICS currency might be backed by a commodity—such as gold and/or other precious metals—much like the dollar was previously backed by gold. If true, that could be a differentiating factor that helps the currency more effectively compete against the dollar.

The BRICS currently control an estimated 5,300 tons of gold, which ranks them second in the world behind the U.S.—the latter of which controls over 8,100 tons of gold.

Potential fallout from further erosion of the dollar

One of the biggest unknowns at this time is the potential impact from a significant hit to the dollar’s current reserve status.

Some experts have projected that it could create serious complications for the U.S. economy, while others have predicted a fairly benign impact.

James Rickards, a former investment banker and previous advisor to both the CIA and the Defense Department, is someone who believes any potential downfall in the dollar would be calamitous for the world economy.

In an op-ed for The Daily Reckoning, Rickards wrote that the new BRICS currency will “affect world trade, direct foreign investment and investor portfolios in dramatic and unforeseen ways,” and cause an “unprecedented […] geopolitical shockwave.”

Rickards expects the new currency to be pegged to gold, or a basket of commodities, and to be offered in a digital format.

On the other side of the spectrum, economist Paul Krugman isn’t buying all the negative hype.

In an Opinion piece for the New York Times titled What’s Driving Dollar Doomsaying?, Krugman mostly dismissed the alarmist perspective, writing, “So ignore all the dollar doomers out there. Or better yet, consider what their hyping of a nonissue says about their own judgment.”

As with most complex and contentious topics, the reality likely falls somewhere in between those two perspectives.

In his article published by the City Journal, Stephen Miran presents a more sanguine perspective on future challenges to dollar dominance. Instead of citing the threat from a near-term competitor, Miran suggests that the dollar is organically losing its place as the world’s reserve currency alongside a resizing of the U.S. economy, in relative terms.

Miran points out that the U.S. economy now constitutes only about 24% of global GDP, down from 40% in the 1960s. As a result, he considers the primary risks to “dedollarization” to be geopolitical in nature.

On that topic, Miran writes, “the U.S. would no longer have the ability to project power globally via the financial system.” Miran also suggests that the consequences of that outcome aren’t easy to predict. “This serious risk lies somewhat beyond the purview of economic evaluation,” he writes.

The geopolitical nature of any downfall in the dollar makes a lot of sense, especially when one considers that the process would likely span many years. For example, when the British pound was demoted to a second-tier currency in the 20th century, that process took decades.

As a result, the risks associated with dedollarization might ultimately be overshadowed by some other significant geopolitical event (or set of events) that shakes up the global financial system more dramatically than any potential decline in the dollar’s role as a reserve currency.

And if the BRICS do successfully launch a new currency, it would likely take many years before the world’s central bankers would be comfortable holding it as a high percentage of their reserves. Moreover, a BRICS currency wouldn’t necessarily tick all of the necessary boxes when it comes to an ideal global reserve currency.

That said, if the BRICS currency were to pressure the dollar sooner than expected, the potential negatives may simply be the opposite of the benefits that the U.S. currently receives from the dollar’s status as the world’s top reserve currency.

Some of the most commonly referenced benefits include lower borrowing costs, increased geopolitical influence, increased financial security and reduced exchange rate risk. If the dollar’s reserve status deteriorates further, it’s no great stretch to think that those benefits might start to evaporate.

But considering all the aforementioned information and data, that probably won’t be happening anytime soon.

For more context on the proposed BRICS currency, check out this episode of Macro Money on the tastylive financial network. To follow everything moving the markets, tune into tastylive—weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastylive or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.