Duck Call

Despite a whimsical name, DuckDuckGo offers a serious privacy-oriented alternative to Google searches

A google search for “luckbox” put a betting site at the top of the results and the magazine’s homepage in the No. 2 spot. A DuckDuckGo search reversed the order, placing the magazine first and the betting site second. That was good enough for us.

But the advantages of DuckDuckGo don’t end with our admittedly prejudiced preference for the results of a single search. DDG was born out of concern for data privacy, an issue of grave importance to informed internet users, says Gabriel Weinberg, the company’s founder and CEO.

“Our mission is to show the world that protecting your privacy can be simple, and our North Star is to raise the standard of trust online,” Weinberg tells Luckbox. “We’re working to make privacy the rule, not the exception.”

DDG promotes privacy because it doesn’t track, record, exploit or sell its users’ search results. Many other search engines, including Google, do the opposite.

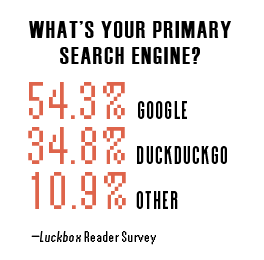

That penchant for privacy pits DDG, a David with 0.61% market share last year, against Google, a Goliath that controls 92.04% of the business, according to the statcounter.com website. DDG brought in $100 million in revenue last year, but Google’s dominance paid off handsomely, earning the company $181.7 billion in 2020—most of it from targeted advertising.

Google can charge plenty for ads because it uses the mountain of data that’s been collected on just about everyone in the world to “customize” search results. When two people use Google to search for “luckbox,” they don’t necessarily get the same results. Google tailors the list of suggested sites to fit each user’s past online activities.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of that customization. For individuals, it can prove helpful, harmful or even dangerous. For society as a whole, it can change the course of history.

Custom searches

First, let’s consider the innocuous or perhaps even beneficial results of a particular customized search.

Suppose a young mother who enjoys gardening types the word “magazine” into the Google search field and hits enter. Google knows enough about the woman to direct her to publications devoted to parenting tips or gardening tools.

A DDG search yields a magazine subscription site at the top of the list, followed by a dictionary definition of the word “magazine.”

So, the user arguably benefits from the customized search.

But think about what happens when a politically engaged citizen who frequents the conservative Fox News website uses Google to search for the word “magazine.” The results would tend to include an array of conservative sites but exclude nearly all liberal sites.

That creates a “filter bubble” that confines the user to only one narrow view of politics. It reinforces preconceived notions and precludes consideration of anything that contradicts them. That deepens society’s polarization and can sway an election.

“We believe Google is continuing to engage in personalized algorithm development that results in filter bubbles, and our research shows this to be true,” Weinberg says.

In 2012, a DDG study indicated Google’s filter bubbles may have significantly influenced the presidential election by inserting tens of millions of more links for Barack Obama than for Mitt Romney. After widespread concern arose about bad actors using filter bubbles to disseminate misinformation in the 2016 elections, DDG studied the 2018 midterms and found that Google had failed to fulfill its pledge to quash filter bubbles.

Bursting filter bubbles

With such pervasive use of personal information already occurring, some observers have opined that it’s too late and too difficult to reverse the trend. Weinberg’s not buying it.

“There’s a lot of skepticism around online privacy,” he notes. Quoting the doomsayers, he says: “Isn’t it too late? Will it make everything worse and less personalized? Do I need a computer science degree to set it up? Do I have to stop using all of the services that I rely on?”

Weinberg contends that the answer is no to all of those questions. DDG is working to protect search, web browsing and email with a single download, he says. The company provides private search, encryption upgrading and tracker blocking, making it all work together to stop companies and governments from compiling detailed data profiles of internet users based on their web browsing history.

DDG sees no need to collect users’ personal information because it can deliver good search responses without it, Weinberg says. Searching and browsing with the company’s apps creates an “ah-ha” moment for users who didn’t think it was possible to use the internet without enduring personalized ads and filter bubbles. Privacy also means a faster internet experience because the company blocks trackers that slow down everyday browsing.

But even a company dedicated to privacy faces formidable obstacles to success in the search engine business.

“Governments around the world are all saying that Google has leveraged its monopoly power in many areas, including search, Android and Chrome, to block search competition,” Weinberg maintains.

Google exercises that control through default settings in browsers and operating systems, he says, describing his competitor as a master at making it difficult for users to replace Google with a competitor. Technically, users are allowed to leave Google, but it might require more than 15 clicks on an Android device, he contends.

However, critics have found fault with DDG, too. Some object to the company’s practice of deleting search results for “content mills,” organizations that crank out low-quality information in search of clicks they can monetize. DDG also deletes results for sites that carry what the company judges to be too many ads.

Proponents of those practices would argue that DDG is performing a function similar to newspapers’ practice of presenting what the editors view as relevant news and filtering out what they find trivial. But exercising discretion in presenting results strikes some observers as wise in light of the friction that companies like Facebook have created by allowing false information about politics and COVID-19 to find a home on their sites.

DDG’s growth

Despite controversy and a tough search-engine market, DDG has grown prodigiously since its inception in 2008. In the last year, people have downloaded the app more than 50 million times, the company says. Traffic has grown enough to make the search engine No. 2 on mobile devices in the U.S., Canada, Australia and the Netherlands, according to multiple sources.

The company began turning a profit in 2014, and annual revenue reached $100 million in 2020. Late last year, the company raised $100 million in mainly secondary investment from new and existing investors.

Although DDG doesn’t track its customers, it does conduct national surveys to uncover clues that can help the company keep growing. The studies indicate word-of-mouth drives adoption as customers tell friends and family about online privacy.

“What that says to us is that when people realize this works, they want to tell other people,” Weinberg notes.

Just the same, DDG invests tens of millions of dollars a year in television, radio and billboard advertising to build brand awareness. The company uses the ad campaigns to spread the word that DDG can help users take back their online privacy, Weinberg says.

Although companies can help individuals protect their privacy, they probably can’t turn back the tide of data exploitation for all of society. That will probably require government intervention, observers agree.

Regulating privacy

“There should absolutely be rules at the federal level that protect people from having their privacy abused for profit without their knowledge, says Weinberg. “We actively advocate for greater privacy regulation and consumer rights around the world.”

Those advocacy efforts include proposing legislation and testifying before Congress. DDG has urged Congress to pass a federal privacy law and to institute antitrust reforms like the proposed Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Actchampioned by Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn. DDG is also campaigning for a House bill that would help protect people’s privacy and make the search-engine market more competitive, the company says.

Meanwhile, DDG is working to promote “do not track” legislation and regulation, the online equivalent of “do not call” lists. Some refer to “do not track” by the acronym “DNT” for short.

In 2019, the company launched a study of the DNT browser setting and found that about a quarter of those surveyed turned it on, yet most weren’t aware that the big sites don’t respect it.

That same year, DDG called attention to the fact companies were using DNT settings for “privacy washing,” the online parallel of “greenwashing” that overstates a company’s effort to do the right thing.

Since then, DDG has helped create Global Privacy Control, or GPC, a proposed standard that would help consumers notify companies of their privacy preferences.

“You can think of it as DNT 2.0,” Weinberg says of GPC. “Like DNT, it’s a technical standard and browser setting. But unlike DNT, it already has some regulatory teeth behind it via California’s (privacy) laws.”

Global Privacy Control is enabled by default in the DDG app and automatically sends a “do not sell” signal to websites under California privacy laws, he notes, adding that he hopes DNT will combine with GPC to form the basis for new laws in the U.S. and abroad.

Even if privacy measures improve through GPC and other measures, the Luckbox staff can’t help but hope one thing about DDG doesn’t change. We like seeing the magazine head the list of results when someone searches for “luckbox.”

Those Pesky Online Ads_

For advertisers, the difference between Google and DuckDuckGo comes down to behavioral ads versus contextual ads.

Google offers clients behavioral ads—sometimes called targeted ads—that are directed toward consumers who have demonstrated an interest in a product based on their web searches.

A company that makes work boots, for example, could target behavioral ads toward someone who’s been visiting the sites of retailers that sell work boots. The ads could appear no matter where the targeted consumer goes online. In other words, she could be on a cooking site, but work boot ads would appear because of previous searches for work boots.

If that consumer feels like she’s being followed, it’s because she is being followed.

DuckDuckGo offers only contextual ads that aren’t based on past web searches. A car dealer, for example, could advertise on a car magazine’s website, placing the ad in a logical context. But DuckDuckGo doesn’t track users, so the car dealer’s ads can’t follow someone who visited the car magazine’s site when she goes to a site to shop for perfume.

On its website, DuckDuckGo summarizes the experience of using its search engine this way: “Each time you search on DuckDuckGo, it’s as if you’ve never been there before.