Operation Bayonet

An international band of cyber police joined forces to bust the bosses of sinister darknet marketplaces

This account of an international crackdown on the internet’s darknet markets was adapted from the Darknet Diaries podcast created by Jack Rhysider.

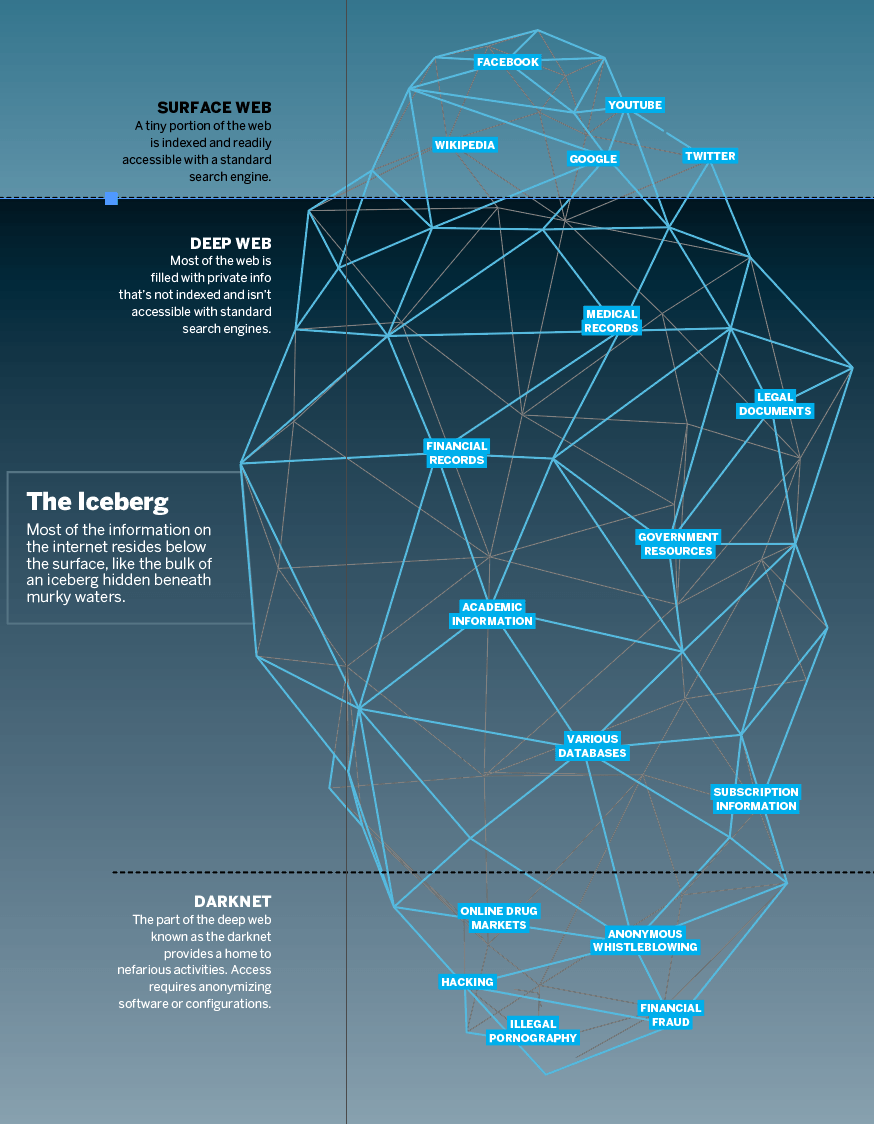

Some background on the darknet could foster a better understanding of the fate that befell a site called AlphaBay, one of the most popular darknet marketplaces ever.

Think of the darknet as a cloak of anonymity that hides users’ identities somewhere in the far reaches of the internet. Better yet, imagine walking into a nightclub where everyone’s required to wear a mask, white shirt, red tie and blue suit. That way, no one can tell the club patrons apart. It’s much the same on the darknet. At least, that’s the theory.

The darknets include Freenet and I2P, but Tor—which stands for The Onion Router—ranks as the most popular, the most feared and the most reviled. Users employ special software to connect their computers to the Tor network and become anonymous. Normally, websites know visitors’ IP addresses, which are associated with where they are geographically. But when users connect to Tor, they get an IP that might be hundreds or thousands of miles away from their actual locations. This masks where users are actually located.

For extra safety, visitors can use a virtual private network, or VPN, to connect to Tor. If Tor or the VPN servers are compromised, neither system would know where the users came from or went. They’d be able to see only one or the other.

The Silk Road

In repressed countries, legions of activists, intellectuals and cautious ordinary citizens use Tor to circumvent censors and make their voices heard. Whistleblowers use Tor to hide their identities. Anyone concerned about mass surveillance may use Tor to escape being tracked. It’s a tool for sharing messages without facing punishment for speaking up. But Tor offers something else, too: It grants access to restricted darknet sites.

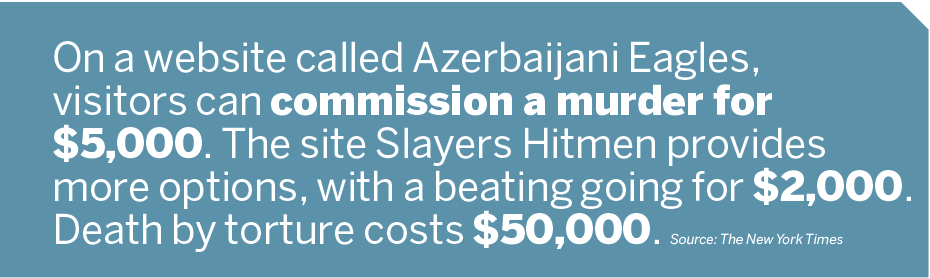

Because Tor theoretically operates an anonymous network, bad guys use it to commit crimes. Tor sites offer to trade software or music illegally. Tor users blog about subjects like how to counterfeit money or how to hack into computers illegally. Drug marketplaces proliferate on Tor. Tor rates drug marketplace sites, providing sellers with scores to help buyers decide whom to trust. Buyers can purchase a sample of any controlled substance to determine if it’s legit—in a debased sense of the word.

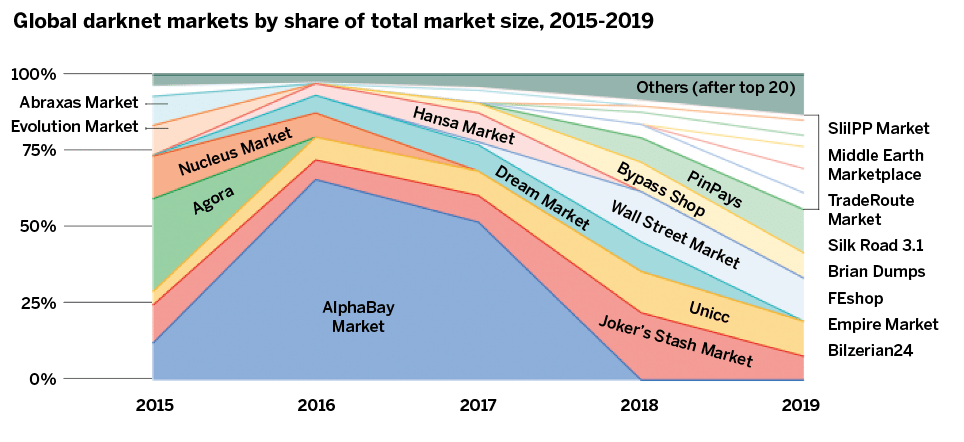

Perhaps the most infamous of all the dark markets was the Silk Road. The feds tracked its founder, Ross Ulbricht, and captured him in 2014. He was convicted on multiple counts of fraud, conspiracy and narcotics trafficking, and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. But some Silk Road programmers and moderators weren’t immediately apprehended, and they went on to create Silk Road 2.0. Within a year, the feds caught up with them and shut down that site, too.

The same month Silk Road 2.0 was shuttered, a new site called AlphaBay sprang up on Tor, and Silk Road “entrepreneurs” immediately began using it to buy and sell drugs. But another big dark market, known as Evolution, was also operating at the time, serving as a marketplace for all kinds of illegal merchandise but primarily as place to buy and sell drugs.

Evolution used an escrow service for transactions. Buyers sent bitcoin to the Evolution server, which held the cryptocurrency until the transaction was complete and then released it. It was dominant and highly rated. But in March 2015 Evolution went offline. This time it wasn’t because of the feds. Whoever was running Evolution shut the doors and absconded with about $12 million they were holding on the site for buyers. It was as though the buyers had paid for their drugs, and the middleman simply split with the cash instead of turning it over to the sellers. Thus the buyers were out the money and had nothing to show for it.

The rise of AlphaBay

At that point, many of the buyers and sellers in the illicit drug trade turned to AlphaBay for online transactions. Within two years, the site was servicing more than 400,000 users and had grown to become the biggest dark market in the world.

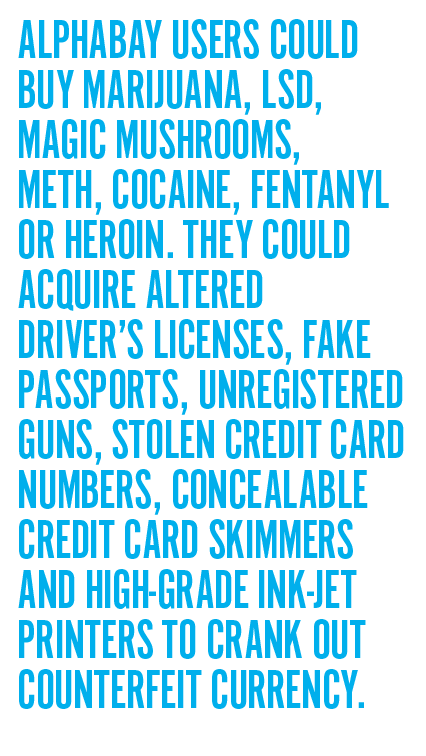

AlphaBay’s friendly moderators taught visitors how to use bitcoin and how to employ Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) to encrypt web chats. Users could buy marijuana, LSD, magic mushrooms, meth, cocaine, fentanyl or heroin. They could acquire altered driver’s licenses, fake passports, unregistered guns, stolen credit card numbers, concealable credit card skimmers and high-grade ink-jet printers to crank out counterfeit currency. Yet despite all those options, drug sales predominated.

Buyers couldn’t use credit cards or PayPal. Only bitcoin, Monero and Ethereum were accepted. Those cryptocurrencies are theoretically anonymous because buyers don’t know who’s receiving the payment. For its trouble, AlphaBay charged 2%-4% commission on every transaction. With hundreds of thousands of transactions, the site was making some serious bitcoin.

AlphaBay hired a staff and continued to add features and fix bugs. But a site like that attracts a lot of enemies. Law enforcement agencies from around the world were working to shut down sites like AlphaBay. Investigations began in the United States, the U.K., the Netherlands, Canada and Germany. The authorities began by seeking clues that could reveal who was running the sites, but at first found nothing.

The Feds catch a break

Undercover FBI agents visited AlphaBay and used bitcoins to buy marijuana. The weed arrived in the mail, but the shipments offered no clues as to who was selling it or who was operating the site. All the agents learned was the marijuana was shipped from California. The agents bought heroin, fentanyl, more marijuana and then 50 grams of meth. Then they bought four fake driver’s licenses and a credit card skimmer that fits onto an ATM.

The FBI, which by now was sharing information on dark market cases with law enforcement agencies around the world, continued to gather inconclusive bits of information until it finally spotted something significant. An agent who created an account received a revealing email message welcoming him to the sinister market.

The header of the email greeting bore the address pimpalex91@hotmail.com. The FBI took the address to Microsoft, owner of Hotmail, and found it was associated with the LinkedIn account of Alexandre Cazès, who was born in 1991. This matched the name and the “91” in the email address. His LinkedIn profile explained that he lived in Montreal and ran a computer tech support company called EBX Technologies.

The FBI dug into the facts surrounding Cazès and discovered that besides his involvement with AlphaBay he was embroiled in Hansa, a popular European darknet marketplace noted for its sophisticated user interface, highly competent admins and exemplary customer support.

Even though Hansa was smaller than AlphaBay, it had attracted the attention of law enforcement. Nearly all the Hansa servers were on the anonymous Tor network, which made it impossible to trace their locations. But one Hansa development server resided on the regular internet. The Hansa admins had been using it to test new features. Researchers reported that intelligence to the Netherlands National High Tech Crimes Unit.

Following the leads

The Dutch agency used the tip to track down the IP in a data center in the Netherlands. They contacted the center and put something akin to a wire-tap on the server to monitor the information packets coming in and out. They found the server was talking a lot with the live Hansa server on Tor. The production server was in the same data center as the development server, so the Dutch made hard-drive copies of a few of the Hansa servers, including those used for development and production. Working directly with the data center, the authorities accomplished that without causing an outage on the site. Next, the Dutch High Tech Crimes Unit combed the contents of those hard drives to identify the AlphaBay admins.

Somewhere in the logs, the Crimes Unit discovered the names and possible locations of the two men running the Hansa dark market. One address was in Germany, but when the Dutch government contacted Germany to request the admin’s arrest and extradition, the German government explained that it was already tracking both suspects. It seems the same two who were running the Hansa dark market had previously created an online site to buy and sell pirated e-books and audiobooks. The German police were trying to find their location to arrest them. So the Dutch and German authorities began collaborating on a new plan. They would capture the two miscreants under the German case, but the Dutch would control the Hansa investigation.

With the help of the Lithuanian government, the Germans and Dutch located the Hansa server. The agencies had everything they needed to arrest the admins and take over Hansa. But then the FBI notified the authorities in Europe that it had also uncovered the details of the case and was about to raid the data center and arrest the owner. So agencies from the Netherlands, Germany and the U.S. teamed up. If the Dutch controlled Hansa, they could collect information on the users of the site and potentially arrest a lot of dealers.

The honeypot

The FBI agreed to the plan and named it “Operation Bayonet.” Bayonet was a play on words: Bay came from AlphaBay, net came from darknet, and together, they would signify piercing the dark marketplace. Authorities hoped that taking down both AlphaBay and Hansa would destroy trust in the dark marketplace for a long time, potentially crippling the whole online trade of illegal merchandise and drugs.

Operation Bayonet was a go. The next step was the takeover of Hansa. The Dutch authorities worked with Lithuania and Germany to coordinate assaulting the data center while simultaneously nabbing the two suspects. On June 20, 2017, the international band of cops sprang into action.

The Dutch police invaded the data center in Lithuania, and the German police executed surgical strikes on the homes of both of Hansa admins. It’s not clear how they accomplished all this, but here’s a likely scenario: The German police probably watched the admins and verified they were on their computers. Then the cops created a disturbance to draw the men away from their computers without shutting down the machines and leaving the Hansa site. The German police gave the signal to the Dutch authorities who then quickly migrated the entire Hansa server to the Netherlands and placed it under their control.

To stay undercover, the German police may have simply filed arrest reports for two suspects caught pirating e-books and audiobooks. That meant visitors to the Hansa site remained oblivious to the takedown.

So the trap was set. The Dutch police had set up a honeypot—or sting operation—by using a popular drug marketplace to attract criminals to conduct crimes under their watchful eye. Now that they were collecting extensive information, they were ready for the FBI to conduct the next step in Operation Bayonet.

The FBI was ready for action. Agents knew the owner of AlphaBay, Alexandre Cazès, was living in Thailand, and they knew the AlphaBay server was situated in Montreal. The FBI coordinated with Canada and Thailand to conduct simultaneous raids on the data center and the Cazès residence. Again, the goal was to arrest Alexandre while he was logged onto his computer, thus proving he was the admin for the site. On July 5, 2017, the FBI and police in Canada and Thailand went on the offensive.

The takedown

The Canadian cops raided the data center and took the servers offline. Simultaneously, the Thai police staged a disturbance outside the opulent Cazès villa to lure their prey away from his laptop. A plainclothes Thai cop in an unmarked police car purposely smashed into the front gate of the house but made it look like an accident. Additional plainclothes cops played the roles of shocked neighbors to add to the chaos. But there was no sign of the suspect even though the authorities knew he was home. The ruckus continued for what seemed like an eternity until Cazès finally emerged with his cell phone in his hand, wearing shorts, sneakers and no shirt.

He was angry about the gate but became truly confused when Thai authorities wrestled him into a pair of handcuffs. The cops grabbed his phone and kept it open so it wouldn’t become locked. The police then proceeded inside and found his computer open and logged into the AlphaBay server as admin. He had been trying to figure out why the servers in Montreal were down.

When the Royal Thai Police and the FBI examined the Cazès computer they found a text file with all the passwords for the AlphaBay site. That would be enough evidence to convict him of owning the largest dark market in the world. The raid on the Montreal data center also succeeded, and the FBI seized his servers and took them offline.

The authorities kept the capture of Alexandre Cazès quiet and did not announce they had shuttered AlphaBay. Angry AlphaBay users suspected an exit strategy similar to the one at Evolution, where the owners ran off with the buyers’ bitcoins. Cazès was thrown into a Thai jail to await extradition to the U.S. Meanwhile, the U.S. filed a civil forfeiture complaint against the suspect and his wife, which allowed the FBI to seize everything the couple owned.

An ill-gotten fortune

Among the seized assets, FBI agents found a meticulously maintained journal that made it easy to locate and collect the family’s valuables. It led the authorities to 10 vehicles, including a $900,000 Lamborghini, a Mini Cooper, a BMW motorcycle and a Porsche Panamera. Real estate holdings included the dark market operator’s primary luxury villa in Thailand and the house next door where his wife’s parents lived. Cazès was building a villa in Bangkok and had vacation houses in Phuket, Antigua and Cyprus. His palatial home in Cyprus cost $2.3 million, the amount required to become an official resident of the island nation. He had also paid Antigua $400,000 to become a resident. He had three Thai bank accounts, one Swiss bank account and one bank account in St. Vincent in The Grenadines.

Cazès was holding large amounts of cryptocurrencies, including bitcoin, Ethereum, Monero and Zcash. Between his bank accounts and cryptocurrencies, the FBI seized $8.8 million. In addition, the FBI seized all the cryptocurrency stored on the AlphaBay servers in Montreal. Those servers had 250,000 active listings, compared with the 13,000 on Silk Road when it was shut down. Cazès was charging a 2% to 4% commission on every transaction, and the logs showed that about 840,000 bitcoins were transferred through AlphaBay, totaling around $450 million. The feds estimated his commissions came to between $9 million and $18 million. According to his notes, he had a net worth of $23 million.

But perhaps Cazès wasn’t just about money. His father described him to a reporter in Montreal as kind and caring. “He wouldn’t hurt a fly,” his father insisted. Cazès didn’t have a criminal record, never smoked cigarettes and never abused drugs. He was so smart that he skipped a year of school.

Still, those brighter days had ended. Cazès sat in jail knowing the authorities were taking everything away from him and his wife. He was concerned about her parents losing their house. He also knew full well that Ross Ulbricht drew a life sentence for running Silk Road. Gripped by fear, he felt the walls closing in and he didn’t want to face his troubles.

His final act

On July 12, after seven days in a Thai jail cell, Cazès twisted a towel into a tightly wound rope, tied it into a sturdy knot to form a noose, put his head through his creation and used the weight of his body to hang himself. The next morning the Thai guards discovered the body, and the news broke in Thailand. The Wall Street Journal informed the rest of the world, noting that the feds had seized AlphaBay and the owner of the site was dead. Frequenters of the dark markets panicked. Conspiracy theories ran wild. Was Cazès murdered by another dark market owner? Maybe someone close to AlphaBay killed him so he would take the fall for everybody? Was it the feds? Why would he commit suicide?

According to plan, new users flocked to the Dutch government-controlled Hansa dark markets as soon as AlphaBay shut down. Every day, more than 5,000 new users were registering at the site—a significant increase from the normal 600. In fact, the volume of new users broke the registration system, and the Dutch police worked for days getting it back online. Under Dutch law they were required to track and report every sale on the site, and users were conducting about 1,000 transactions a day. The paperwork was becoming too much for the Dutch authorities to handle. After 27 days, the Dutch government pulled the plug on the server, shutting down the whole operation—but not before collecting information on about 27,000 transactions.

The Dutch authorities placed a banner on the site saying it had been seized by the Dutch National Police. At the same time, AlphaBay’s site started displaying the message that the FBI had seized it. News that government agencies controlled both sites shattered the trust of many dark market buyers and sellers, sending the drug-trafficking community into chaos.

The FBI gathered more evidence and then arrested the AlphaBay moderators. The Dutch police, collected information on more than 420,000 users, including 10,000 home addresses, turning the information over to Europol for further action. The Dutch seized about $12 million in bitcoin that was on the Hansa server and arrested more than a dozen dealers in the Netherlands. To this day, the FBI and Dutch police continue to sift through the data they collected to track down suspects and build criminal cases.

When AlphaBay and Hansa went down in rapid succession, the busts rattled the dark market communities. That’s why the Hansa shutdown didn’t trigger a mass migration to another site. Instead, users scattered. They returned to the streets or simply gave up on their criminal activity altogether—at least for a while. The feds had not only infiltrated the darknet but also penetrated the minds of the denizens of the darknet. Some learned caution. Other gave in to panic. In fear and seized by confusion, they got sloppy, suddenly reusing passwords, accidentally revealing their home addresses and just generally becoming negligent about protecting their privacy.

So the raids indisputably shook up the dark market trading scene. But why wouldn’t they? After all, this was the most elaborate sting ever conducted on the darknet.

A darknet-focused podcaster

Jack Rhysider, a network security engineer, created the Darknet Diaries podcast in 2017 because no one else was chronicling the evils of the darknet. The podcast exposes the true stories of hackers, malware, botnets, breaches and privacy—all in an investigative style that bring to mind detectives in fedoras and trench coats. (Check it out!) He still finds time to devote to a tech blog called TunnelsUp and a podcasting blog known as Lime.Link.