Rising Prices, Declining Confidence

Uncertainty prevails as inflation unnerves consumers and perturbs economists

Prices are soaring and necessities are scarce as annual inflation of 6.8% grips the nation.

While economists differ on how much of the blame to assign to monetary policy, labor shortages, supply-chain disruptions, working from home or the spread of the Delta variant, a consensus is emerging among the experts that this round of inflation doesn’t seem transitory.

“It’s the classic inflationary scenario of having too much money chasing too few goods,” said Alan Cole, former senior economist for Congress’s Joint Economic Committee and author of the Full Stack Economics newsletter.

That nearly unprecedented shift in spending increases demand for goods and puts pressure on supply, causing prices to rise, noted James P. Sweeney, chief economist for Credit Suisse.

“About two-thirds of consumption and half of GDP is services spending by households,” Sweeney said. “It almost never contracts. In fact, it’s only contracted two or three times in 75 years. And this time, it absolutely plunged.”

The resulting inflation has prompted legions of economists to abandon their laissez-faire attitude toward controlling prices, observed Carol Corrado, former chief of industrial output at the Federal Reserve Board and now research director in economics at The Conference Board.

Meanwhile, some economists argue that inflation is merely masking the deflationary forces at work in the economy. Technological advances like robotics and artificial intelligence will continue to force prices and reduce the need for human labor, said entrepreneur and author Jeff Booth. (For more on deflation, see pp. 28 and 49.)

Whatever position economists take on inflation and deflation, they tend to agree that demand for merchandise has remained strong during the pandemic, at least partly because the federal government has kept income at or even above pre-pandemic levels despite staggering levels of joblessness.

The first wave of federal relief came with the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, betterknown as the CARES Act, which pumped $2.2 trillion into the economy as direct payments, augmented unemployment benefits and forgivable business loans. President Trump signed the bill into law in March 2020, after the Senate passed it unanimously and the House passed it on a voice vote.

It was the biggest stimulus package ever but only marked the beginning of the effort to keep America whole despite the ravages of the pandemic. A year later, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act, pushing another $1.9 trillion into the economy. That measure passed the Senate 50-49 and the House 220-211.

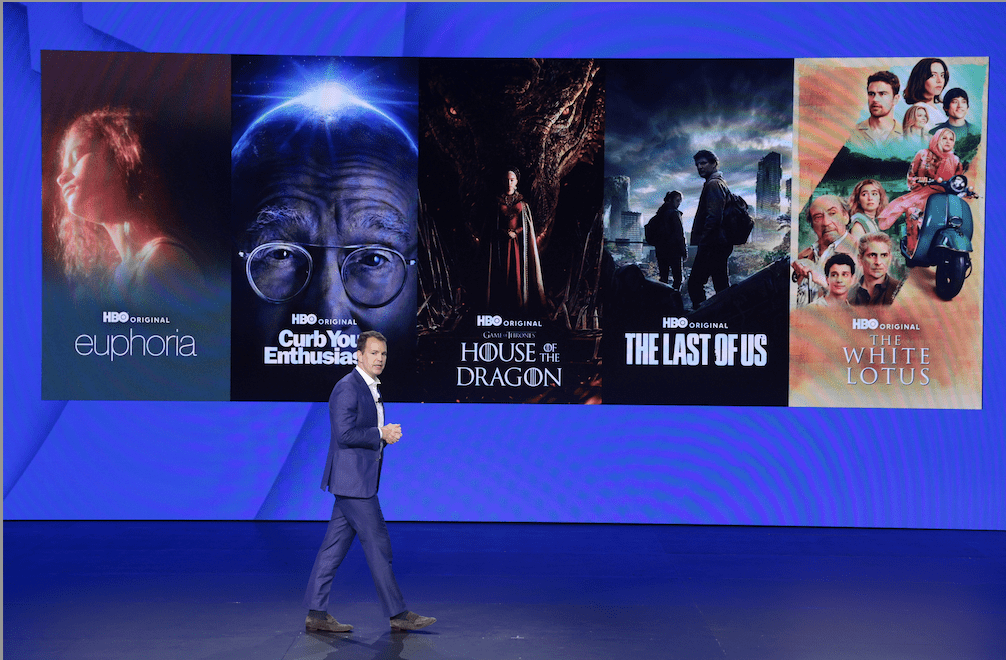

But economic stimuli could do nothing to prevent changes in spending habits wrought by the virus. People could no longer congregate in bars, restaurants, theaters or music venues because of quarantines, lockdowns, layoffs and social distancing. They became shut-ins, working from home and entertaining themselves with electronics.

As a direct result, they cut their spending on services, leaving them with the funds to increase the amount they spent on merchandise. Meanwhile, the supply of goods was shrinking because the pandemic was preventing workers from going to their jobs and making things.

A shortage of workers was also creating bottlenecks in supply chains, making goods more difficult to obtain. Container ships from China waited outside U.S. ports because not enough longshoremen were available to unload them. Trucks sat idle across North America, waiting for drivers.

As if to prolong the problem, workers furloughed by the pandemic have been slow to return to low-wage jobs, and many with higher incomes are choosing early retirement. Before COVID, America employed nearly 153 million workers, but by October the number had climbed back up to just 148 million. Viewed another way, 81% of prime-age workers were employed before the virus struck, and now 61% have returned to the workplace.

If employers are forced to raise wages to attract workers, inflation would naturally result. And as employers take on inexperienced new workers in the face of labor scarcity, the inefficiency of those new hires also raises the prices of the goods they produce.

Even after the pandemic, the labor market could remain tight and continue to fuel inflation for another 10 years, some economists believe. Wages may continue to rise because they have been depressed because of the decline of unions, automation that eliminated jobs and increases in employment overseas.

But there’s reason for cautious optimism. After the initial shock, supply-side issues tend not to get worse and thus prices won’t increase again after the initial adjustment. Sometimes the unfavorable situation improves, and prices can fall. For example, a new worker tends to gain efficiency and thus become less of a force for inflation.

On the other hand, some types of inflation have already occurred and have not been taken into account. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) bases measurement of rents on leases, some of them signed before COVID raised prices.

So how will this all sort itself out?

The world seems unlikely to return to anything resembling the runaway inflation of the 1970s, according to Cole, the newsletter author and former Congressional staffer. The world’s aging population is saving for retirement, he said, which leaves less money to bounce around and drive up prices.

But even if inflation doesn’t reach record highs, Americans would do well to prepare for a wild ride that might last through 2022, a growing number of economists agree.

Auto correct

A breathtaking bout of inflation is roiling the market for new and used cars as increased demand meets pandemic-induced supply issues. No one’s ever seen anything like it.

“Prices are at their highest ever,” reported Jonathan Smoke, chief economist for Cox Automotive, which owns Kelley Blue Book, autotrader.com and Manheim Inc., reputedly the world’s biggest wholesale auto auction.

Pre-COVID, new car buyers paid an average of 94% of the manufacturer’s suggested retail price for cars, but now they’re shelling out a jaw-dropping 101%—more than the sticker price on the window, according to Smoke.

In September, the average price paid for a new car surpassed the $45,000 barrier for the first time, and that was when the average sticker price was $44,400, he said.

But that’s nothing compared with what’s happening with used vehicles. In October, used car prices were up 37% year over year, and that followed a year when they increased 14%, according to Smoke’s stats.

In normal times used cars lose about 10% of their value every year because of wear and tear, Smoke noted. But shortages of used cars remain so acute that some two-year-old vehicles are selling for more than they cost when they were new, he said.

Today’s $15,000 used car has typically clocked 40,000 more miles on the odometer than a car that sold for that amount pre-COVID, Smoke noted.

It’s happening because some urban workers are choosing to drive private vehicles to the job instead of risking COVID on public transit. Meanwhile, working remotely is enabling some employees to move farther from city centers and thus increase their commitment to private modes of transportation.

Before the pandemic, the number of vehicles in the United States typically grew by about 5 million annually. Last year, the nation experienced the first contraction in its stock of vehicles since the Great Recession, Smoke said. In other words, automotive manufacturers have yet to catch up from COVID-related shutdowns and semiconductor shortages.

When will it end? Used car prices should begin falling next spring after the rush to buy them with income tax refunds subsides, he predicted.

“The new vehicle market may see abnormal price increases for longer than that—as long as supply continues to be relatively constrained,” Smoke warned, “through at least next year and into 2023.”