Shein IPO: Flashy Growth, But Doubt and Risks Abound

After several years of blistering growth, the fast-fashion retailer Shein has indicated it will pursue an IPO in the U.S., but an approval to list is by no means guaranteed

- Shein has aggressively grown its revenues over the last several years, and could generate more than $30 billion in sales this year.

- Shein was the most searched (via Google) fashion retailer last year.

- The Singapore-based company has indicated it intends to pursue an initial public offering (IPO) in the United States at some point in the near future.

- In order to list in the U.S., Shein may first have to prove that the company does not utilize forced labor in China.

Investors and traders looking to own a piece of the “fast-fashion” industry will be intrigued to hear that Shein (aka “SHEIN”) is considering an initial public offering in the United States. And via this listing, the fast-fashion innovator is hoping to achieve a valuation of at least $90 billion.

Having quietly grown at a brisk pace, Shein is no longer an up-and-comer. It’s a fashion juggernaut. Last year, Shein was the most-googled fashion brand in the world, and the second-most downloaded shopping app in the U.S.

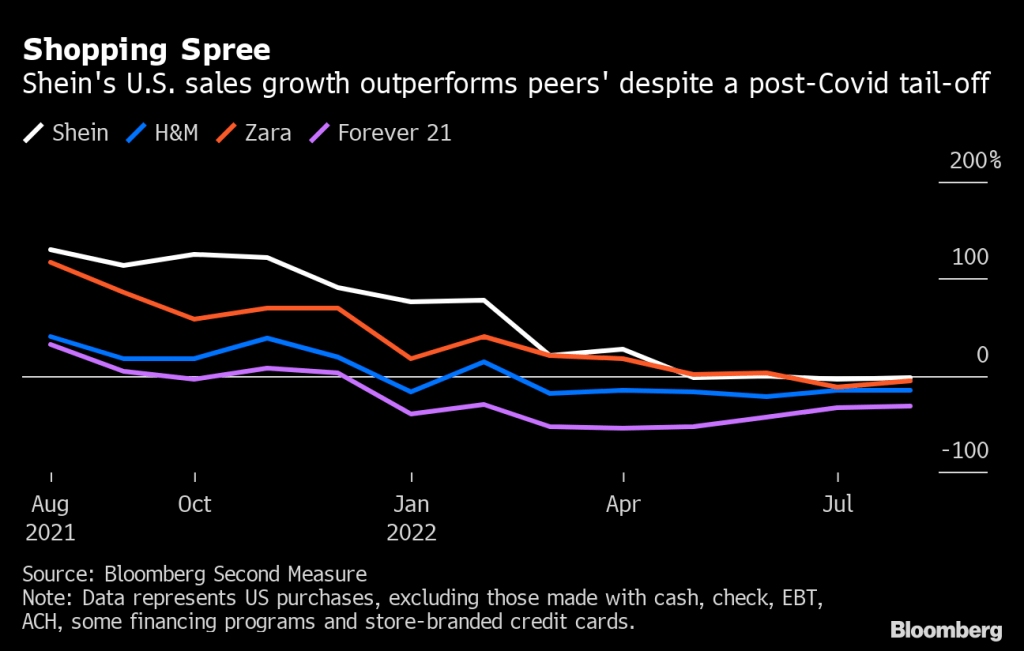

Shein didn’t invent fast fashion, but it has optimized it, and in the process leap-frogged many of its competitors, such as H&M (HNNMY) and Zara (part of Inditex).

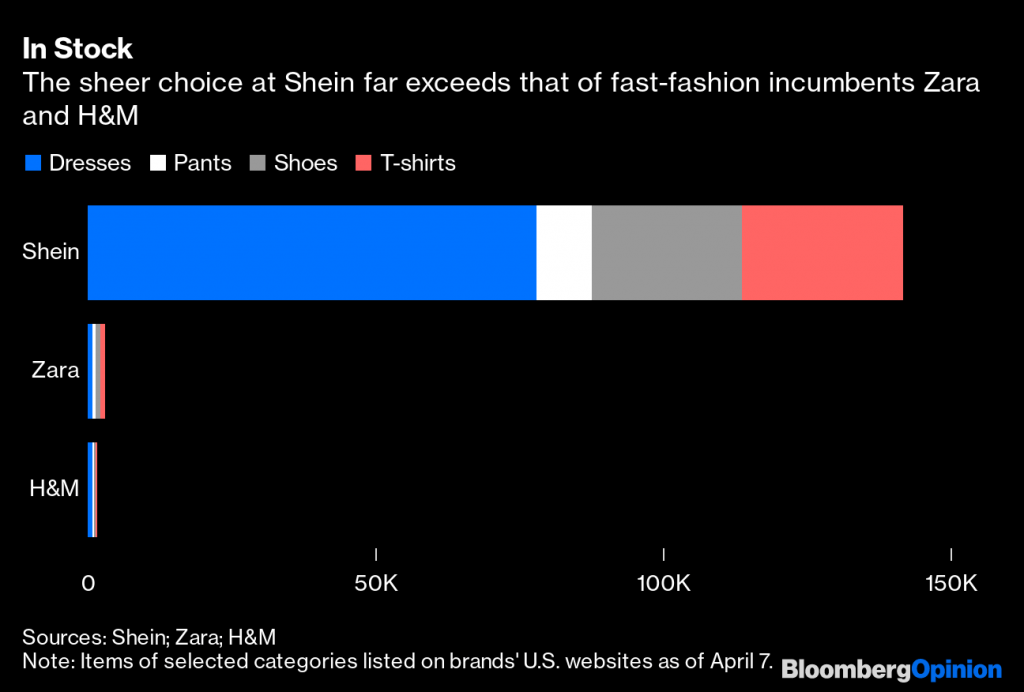

In the digital era, fast fashion refers to the process of identifying emerging fashion trends, and then exploiting them by quickly bringing them to market. When it comes to fast fashion, no one does it better than Shein. According to the Harvard Business School, Shein is the largest fashion retailer in the world by unit volume.

So how does Shein do it? It starts and ends with technological innovation, as one might expect in the current era.

Leveraging a digital-first approach, Shein tracks emerging fashion trends and then uses its extensive marketing savvy to generate demand for products that match those trends. Moreover, Shein has cultivated a tight-knit supply chain, which utilizes a nimble approach to quickly respond to the ever-changing preferences of industry.

Ultimately, nobody can match Shein when it comes to how quickly it can bring a new design to market. Reports suggest that suppliers have three days to provide Shein with samples of new designs, or potentially be cut from the Shein network.

The company’s approach is so effective that many analysts refer to the company’s business model as “real-time retail.” Somewhat like an advanced just-in-time (JIT) inventory management system.

To execute its lightning-fast turnaround, Shein relies on roughly 6,000 suppliers, most of which are located in and around Guangzhou, China. The company also has thousands of its own employees scattered across China, Singapore and the U.S.

Shein’s business model isn’t actually that different from others in the industry. However, much like the inventor who turned bread into sliced bread, Shein has leveraged available technologies to outshine its competitors.

At the front-end of its business model, Shein uses artificial intelligence (AI) to assist in the identification of emerging fashion trends. Once a promising design is identified, it places a small order with a trusted vendor in its vast supply network.

The company then floats the new product through its robust network of digital marketing channels, including a wide array of social media influencers. If there’s interest in a garment, the company quickly ramps up its order sizes.

Shein is effectively a go-between for customers and factories. And its network of small and medium-sized low-cost clothing manufacturers in China allow the company to quickly adjust to rising volumes, and ever-changing demand preferences.

On top of that, most of the company’s orders are shipped directly to the customer. That means Shein has mostly bypassed the expenses associated with brick and mortar retail locations, and still manages to outsell most of its competitors.

The company is so efficient at identifying new trends and bringing them to market that Shein created 20 times the number of unique garments as H&M and Zara (combined) in 2021, according to research conducted by the Harvard Business School.

Shein primarily targets customers in Australia, Europe and the United States. According to Wired, Shein controls an estimated 28% of the fast-fashion market in the U.S.

IPO Outlook and Potential Valuation

Shein has taken the retail world by storm, but that doesn’t mean the company hasn’t faced headwinds.

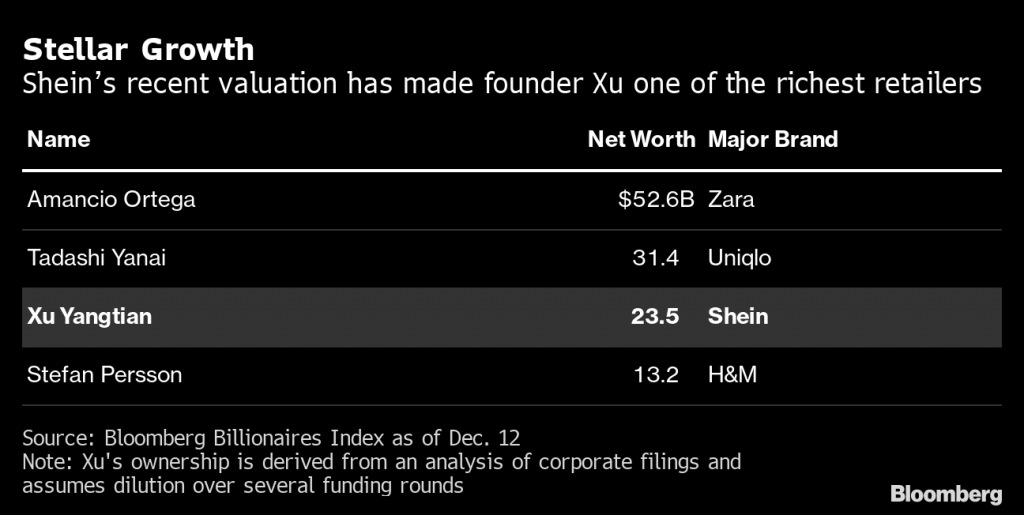

Last year, the company raised $1 billion in capital which implied a $100 billion valuation. However, earlier in 2023, Shein conducted another capital raise which indicated a valuation of only $66 billion.

Shein is a private company, which means it doesn’t publicly disclose detailed financial information. However, Shein has raised capital in recent years, so it’s been forced to release some of its financials to potential investors.

Using available data, analysts have pieced together estimates for Shein’s annual revenues. Last year, Shein garnered around $23 billion in sales. Prior to that, Wired estimates that Shein collected $10 billion in sales in 2020, and roughly $16 billion in 2021.

Assuming $23 billion in sales and a valuation of $66 billion, one can thus compare Shein’s valuation to some of its competitors.

For example, H&M pulled in an estimated $22 billion in sales last year, and has an associated valuation of $24 billion. H&M’s valuation peaked back in 2013 at nearly $75 billion, but has steadily trended lower over the last decade.

In comparison, Zara’s parent company—Inditex (IDEXY)—posted annual sales of about $35 billion in 2022 and currently possesses a market capitalization of roughly $115 billion. But one has to keep in mind that the Inditex umbrella extends beyond just Zara, and includes other brands such as Massimo Dutti, Bershka and Pull & Bear.

If Shein’s 2023 sales growth is on par with recent years, the company could pull in somewhere in the neighborhood of $35 billion in revenues this year, which would put it right in-line with Inditex. That assumes 50% year-over-year growth in sales, which was the company’s average growth rate from 2020 to 2022.

Interestingly, that figure closely mirrors previous guidance from Shein, which suggested it could grow its annual sales to more than $50 billion by 2025. If Shein gets even close to those figures in 2023 and beyond, it’s easy to argue that the company’s valuation should be on par with Inditex, or even higher.

On the other hand, little is known about Shein’s profitability, and when that becomes more clear, the company’s overall valuation estimate will need to be tweaked accordingly.

All told, the above suggests that Shein could represent an attractive investment if the IPO is priced at the company’s target valuation of $90 billion. That’s assuming Shein continues to grow its annual sales at the same rate it has in recent years, and that the company’s profits are also in-line with competitors.

But if the Shein IPO prices at $100 billion or above, investors and traders may need to reassess the Shein value proposition. Under that scenario, the potential risks of investment may outweigh the rewards, as detailed in the next section.

Risk factors: Political and environmental headwinds are significant

Looking beyond Shein’s innovative approach and impressive growth, there are several key risk factors that investors and traders also need to consider as part of any potential investment into the company.

One of the biggest criticisms of the Shein business model is the purported exploitation of workers, particularly at the Chinese textile factories that supply the company.

In 2021, a digital publication known as Sixth Tone investigated the working conditions at some of Shein’s suppliers and found that the situation left “thousands of Chinese workers vulnerable to exploitation.”

Basically, the short turnaround time that makes Shein so successful relies upon an extraordinary effort from its suppliers. And the burden of meeting Shein’s aggressive deadlines usually falls upon the shoulders of the textile workers.

A journalist from Wired traveled to China and interviewed employees from the factories that supply Shein. Through those conversations, it was discovered that many of them are working seven days a week, and often for 10-12 hours a day, with maybe one or two days off a month.

Other separate investigations have revealed similar working conditions at Shein-affiliated textile factories, as detailed in the documentary Untold: Inside the Shein Machine.

Moreover, the nonprofit Remake, which advocates for better labor and environmental practices, rated Shein a 0 out of 150 on its sustainability scale. In its report, Remake indicated that Shein’s suggestion that its factories were “ISO certified” was misleading. And that few of the company’s claims regarding its fair labor practices could be independently verified.

An internal audit conducted by Shein supposedly found many of the same shortcomings. Of the 700 suppliers assessed by Shein, 83% were found to be operating with major social impact risks. And not surprisingly, one of the most common violations was “working hours.”

This issue is so significant that Shein could actually be barred from listing in the U.S. At present, a bipartisan group in Congress is also evaluating whether Shein’s business model relies on forced labor, which could disqualify the company from pursuing an IPO in the U.S.

The aforementioned Congressional group recently sent a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requesting that the watchdog independently verify that Shein does not rely on forced labor before clearing the company to pursue an IPO in the U.S.

On top of those labor-related concerns, the company has also been the subject of criticism for its negative impact on the environment. As a reference point, Oxfam previously estimated that the fashion industry is responsible for about 10% of the world’s annual global carbon emissions.

And as a result of Shein’s soaring popularity, an independent nonprofit named Synthetics Anonymous recently revealed that Shein’s consumption of oil and virgin polyester equates to the same level of annual carbon emissions as 180 coal-fired plants.

Unless changes are made in the near future, fast-fashion’s carbon footprint could increase dramatically by 2030, according to the Ellen Macarthur Foundation.

One of the other major issues facing not only Shein, but the broader fashion industry, stems from garment-related waste. As many are well aware, the price points at H&M, Shein and Zara are often quite low, and not surprisingly, the quality of these garments also tends to be poor.

For this reason, fast-fashion is often seen as a “throwaway” industry, because consumers of fast fashion don’t usually wear these items very often before they are sold or discarded.

Consistently wearing new clothes might be an effective method of attracting new followers on social media, but it’s a lot more problematic when it comes to the environment. In the U.S. alone, it’s been estimated that an astounding 34 billion pounds of used textiles are discarded annually.

Moreover, an estimated 66% of that total ends up in landfills. And the situation is equally dire outside the U.S. In Chile’s Atacama Desert, for example, there’s a mountain of decaying textiles weighing roughly 60,000 tons, which is now visible from space.

Tragically, recent research has revealed that less than 1% of discarded textiles are recycled into new clothes. So with 100 billion new garments being produced annually, this problem is only getting worse.

Obviously, Shein isn’t the lone culprit, but the company is poised to grow at a faster rate than H&M and Zara in the coming years, suggesting that its environmental footprint will soon be the biggest in the industry.

As such, the aforementioned dynamic represents a real risk for Shein’s business model, because at some point in the future, consumers could change their preferences, and attempt to hold the company to a higher environmental standard.

Considering the aforementioned issues, it’s fairly safe to say that socially responsible investors and traders will be steering well clear of a potential Shein listing—if one does in fact materialize.

Final Takeaways

Growing at a blistering rate since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Shein has taken the fashion industry by storm.

Looking purely at the numbers, Shein’s potential IPO at a valuation of $90 billion could represent an attractive entry point into a company that looks poised to build on its already considerable fortunes.

On the other hand, assessing Shein’s value proposition more holistically, the political and environmental risks associated with this company are substantial in nature. And in that regard, socially conscious investors may choose to avoid Shein, no matter the valuation.

For context, one must also consider that H&M peaked in valuation back in 2013 at more than $75 billion, and has since trended lower to roughly $24 billion. Some of that is due to increased competition from Shein and Zara.

This example helps illustrate that Shein’s business model is also susceptible to the emergence of another competitor, or to a shift in consumer preferences. Considering the fickle nature of the fashion industry, these potential headwinds can’t be easily dismissed.

At present, there’s no definitive timeline for Shein’s debut in the U.S. stock market. In fact, a U.S. listing may never materialize, based on the aforementioned Congressional investigation into the company’s potential affiliation with forced labor.

If Shein doesn’t receive approval to list in the United States, the company would likely pursue a listing closer to home—such as Singapore or Hong Kong. In that case, Shein shares might eventually be offered over-the-counter (OTC) in the U.S. That means, for the time being, investors and traders should continue to collect information about this promising—but potentially complicated—future listing.

To follow everything moving the markets, including the latest IPOs, tune into tastylive—weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Andrew Prochnow has more than 15 years of experience trading the global financial markets, including 10 years as a professional options trader. Andrew is a frequent contributor Luckbox magazine.