SPAC Bubble Babble

Don’t worry about the market’s supposedly overheated penchant for SPACs. Worry about the armchair SPAC experts. And consider the risk-free WeWork trade.

In August 2019, the news broke that one of the world’s hottest startups was planning its initial public offering.

At first, hungry investors salivated at the prospect of biting into one of the most succulent new commercial real estate trends. But they soon lost their appetite.

The company’s S-1 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission revealed structural problems, spiraling debt and ill-advised loans to its CEO.

Many questioned whether the company would ever turn a profit.

The IPO collapsed. The CEO exited with a multi-billion-dollar payout. And the company’s lofty $49 billion valuation turned into a punchline.

But less than two years later, WeWork was looking to go public again.

This time, however, nobody was talking about a traditional IPO, and the shared-workspace company’s valuation had been cut by 80%.

But the company shared documents with potential investors that said it would seek $1 billion through a deal with a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC—a company formed to acquire a private company and take it public.

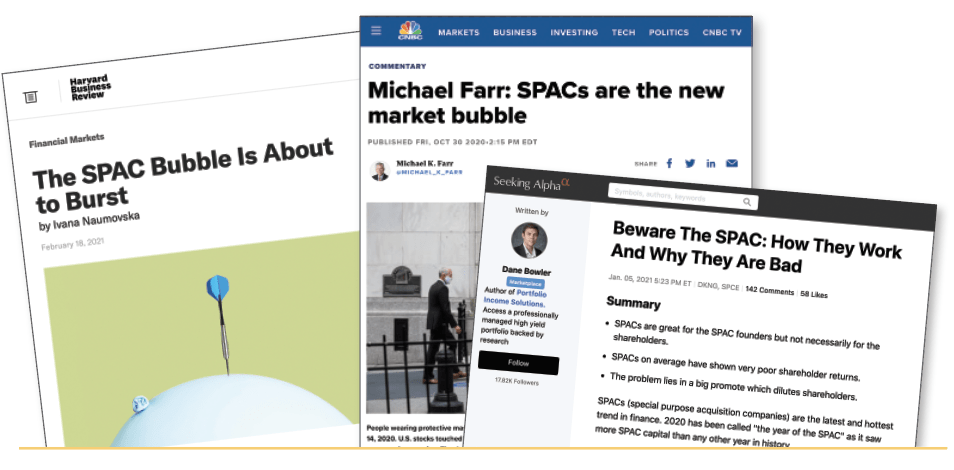

The media and academia responded with a frenzy of criticism.

Reporters and talking heads gnashed their teeth as they slapped their keyboards. Tying WeWork to SPACs was a dream come true for headline writers and for reporters who’ve been pumping the word “bubble” into the first paragraph of any story about SPACs.

Meanwhile, academics, whose tweed jackets had grown tighter after a year of pandemic-dictated confinement to their armchairs, screamed to the financial gods about the alleged foibles of SPACs.

The press and academe were united in their insistence that any WeWork deal would expand the “SPAC bubble.” Their musings became the newest chapter in the media’s long-running critique of SPACs.

Three considerations

First, criticism of SPACs often centers on a profound misunderstanding of venture-forward vehicles, and it’s nothing new.

Second, savvy traders aren’t daunted by the volatility implied by a perceived bubble.

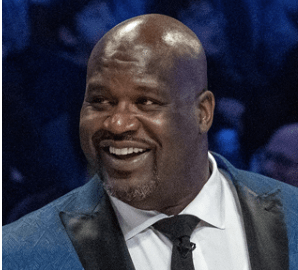

Third, virtually no one was discussing the possibility that WeWork might align with Bowx Acquisition Corp., the SPAC aligned with former NBA star Shaquille O’Neal.

Still, the speculation alone created something beautiful for anyone with money to put to work—a risk-free trade one could leverage to the hilt.

And everyone who was stuck in the conversation about a supposed bubble was failing to grasp the meaning of the opportunity.

But for some, that trade has been at the heart of two moves that have generated incredible returns.

Best of all, regardless of all the bubble talk, traders have a chance to exploit this type of deal immediately.

But first, let’s delve into the care and feeding of SPACs.

All the world’s a bubble

Are SPACs in a bubble? Every day, another flurry of headlines suggests wild deal-making and rampant speculation in the land of SPACs. But everyone should know better.

In the world of behavioral finance, SPACs are a source of anomalies. In some cases, they create risk-free trades as clean as a pile of cash just off the government presses.

In other cases, they create head-scratching speculation that might rival the cryptocurrency craze of 2017 or the non-fungible token bonanza of 2021—at least on the surface.

Either way, two factors fuel speculation at the formation of a SPAC.

First, there’s the degree of confidence investors have in the SPAC management team’s business history. Investors scrutinize the individuals who will lead the SPAC, raise the capital and acquire a profitable private company.

For example, investors view the reverse mergers of DraftKings and Skillz as success stories. Those achievements have triggered significant interest in the next SPAC announced by Hollywood executive Jeff Sagansky and his longtime business partners Harry Sloan and Eli Baker at Soaring Eagle Acquisition Corp.

Even before Soaring Eagle announced a deal, shares in the SPAC have traded as much as a 12.9% premium to the trust value (or $11.29 per share).

The fact that the investment community values shares in a SPAC at more than their trust value of $10 isn’t based on the expectation that the cash itself will somehow gain in value. Before a deal, the added value is tied solely to confidence in the team leading the SPAC.

The second and more important factor in evaluating a SPAC’s potential is the size of the pile of cash it has amassed. It has to raise enough funds to buy a promising company.

Safety in SPACS

Early investors have to evaluate SPACs that haven’t acquired a targeted company. That’s why some analysts find fault with SPACs or believe that the proliferation of SPACS indicates they’re in a bubble.

But two elements are driving the bubble sentiment.

First, retail investors typically aren’t familiar with alternative investments. While it’s true that SPACs are speculative and volatile, most venture capital deals are speculative, volatile and—a key distinction—highly illiquid. SPACs offer the safety of guardrails that prevent excessive losses.

Industry experts know those guardrails well, but the media fail to explain the benefits and the possibilities of taking part in the pre-deal flow.

A traditional unit includes one common share and typically a warrant, which is a call option issued by the company. These derivatives allow the buyer to purchase a fractional share later at an exercise price of $11.50. Warrants usually last for five years after the merger.

Also, funds raised in the SPAC’s IPO are allocated to an escrow account of liquid treasury notes that generate interest. Once a deal occurs, the units unbundle and allow the buyer to trade the warrants and shares differently.

But the most enticing pre-deal opportunity for investors is the “approve or redeem” clause that comes with being a unitholder.

After a SPAC announces what company it has acquired, unitholders either approve the deal or simply reject it and redeem for the original $10, plus the chance to keep the warrants.

Investors who keep their speculation at bay can significantly reduce risk. But unit prices sometimes surge just on the announcement of the SPAC’s formation.

The reason people are speculating on piles of cash and SPAC teams might have less to do with the nature of venture capital and more to do with broader market conditions.

In a world where illiquidity is the enemy of significant economic downturns (ask Ben Bernanke), the Federal Reserve has just infused the economy with an incredible amount of capital, and the U.S. government is unleashing multiple rounds of stimulus.

Inflation might not show up in the Consumer Price Index, but it has surged in all asset classes. People are paying more for less, especially in the S&P 500.

Money has to go somewhere. And in a world of non-fungible tokens, record asset prices for alternative investments and sky-high housing costs, what makes SPACs worthy of criticism?

Let’s return to the fact that while everything else feels frothy—meaning overpriced—SPAC arbitrage is alive and well.

A recent headline in The Financial Times might set Bloomberg terminals on fire. “WeWork tells investors it lost $3.2 billion last year as it woos them for SPAC deal,” it said.

The accompanying article displayed all the voyeuristic elements of reality television. The writer described “Project Windmill,” a treasure trove of documents outlining a plan to locate a SPAC.

Someday, investors may look back at the risk-free WeWork SPAC and wish they had seized the opportunity.

The risk-free SPAC trade

On its books, WeWork had slashed capital expenditures from $2.2 billion in 2019 to $49 million in 2020. COVID-19 had caused its occupancy rates to tumble 72% year-over-year. And the company sought a valuation of roughly $9 billion with debt.

That gave anyone with a financial blog the opportunity to rekindle the love of bashing the ill-fated WeWork deal and play a redemptive game of Where Are They Now with SoftBank financiers who’d found hope in a string of recent positive IPOs.

The market quickly panned any potential WeWork deal despite the lack of details and without a deeper understanding of what type of negotiation or valuation BowX, the SPAC supposedly connected with the deal, might seek.

The trust value is $10 per unit with warrants. Yet, the value of the units fell below $10 to as low as $9.77. Shares had previously retreated to as low as $9.53. Because the WeWork deal hadn’t been consummated, the shares were up for grabs for anyone who might want to redeem them should a deal be announced.

Once the SPAC announces an acquisition target, shareholders have 24 to 48 hours to vote on the deal. Sometimes the markets like the deal, and other times they do not. But shareholders can redeem their shares for that $10 price.

If buyers redeem shares purchased for $9.50, they’ve locked in a guaranteed 5.2% return with interest and no downside. Also, the buyer is allowed to keep the warrants, which have distinct value, more than five years.

A no-brainer opportunity

Mark Yusko, CEO of Morgan Creek Capital Management, considers the SPAC structure one of Wall Street’s best alignments and a no-brainer arbitrage opportunity for his investors.

“I can buy the IPO, or I can buy it below the IPO price even better,” he said. “I hold it to the deal. And now I get to choose, right? Thumbs up or thumbs down. If I’m thumbs down, I get my cash plus interest.”

Yusko’s praise doesn’t end there. “If I can buy $10 for $9.50, I will do that all day,” he said. “I’ll do that with leverage because there is no outcome where I can lose money. It’s risk-free arbitrage.”

The only cost is losing the opportunity to use the capital elsewhere for two years if the SPAC doesn’t acquire a company within that mandated time period, he noted.

By definition, shares shouldn’t fall under $10. Yet, they do. In the last 52 weeks, SPACs headed by Sam Zell (Equity Distribution Acquisition Corp.) and Michael Dell (E.Merge Technology Acquisition Corp.) had prices of $9.32 and $9.53, respectively.

But Yusko and other experts aren’t just taking advantage of the risk-free opportunity to buy pre-deal SPAC shares for less than $10.

News of a deal

Another strategy that institutional investors have adopted centers on embracing the guardrails SPACs offer and capitalizing on the behavior that comes with news of a deal.

Tim Melvin, an analyst at Thunderclap Research, an independent publisher of financial information [Editor’s Note: This author has a similar role at Thunderclap and is related to Melvin], has covered the SPAC business for more than a decade.

One of the few people who read quarterly 13F SEC filings and annual private-equity 10-K SEC filings cover to cover, Melvin has noticed a trend among institutional investors.

According to Melvin’s analysis, Apollo Global snapped up stock in as many SPAC IPOs as possible. Following the IPOs, it either sold after the announcement of a deal or rumors of a deal.

Meanwhile, Saba Capital launched a SPAC fund and promised it would never pay more than 105% of a SPAC’s trust value. The strategy has been to buy a SPAC for no more than $10.50 and then sell it if a pop comes after a deal announcement or news of a rumor. Organizations that have followed suit include the hedge funds Bulldog Investors, Tudor Investment Corp. and Yusko’s exchange-traded fund at Morgan Creek Capital.

“We run a separate fund that does SPAC arbitrage,” Yusko said. “It buys the IPO. It holds the cash, and the trust sells on the deal.”

SPACs have arisen because markets have provided fewer incentives to bring companies public over the last 20 years, according to SPAC attorney Douglas Ellenoff (see p. 22).

This fact is commonly lost in the analysis of the framework of the broader market. The ongoing public narrative also displays an incredible lack of awareness about SPAC redemptions and other guardrails.

Ellenoff noted that SPAC deal-making is a time-consuming process that requires extensive diligence to bring the management team together with the right target.

Leading SPAC dealmakers Neil Shah, at Evercore, or Bennett Schachter, a managing director at Morgan Stanley, reportedly spend significant time evaluating every potential deal’s pros and cons. They also put in a considerable amount of time to match SPAC sponsors with the right private deals.

The value of all that homework seems lost on anyone who believes that companies indulge in mergers and acquisitions solely for the purpose of speculation.

In the case of WeWork, it was a deal that clearly worked out. The valuation appears to have been appropriate. The management team is strong. Investors could have made that risk-free purchase under $10 and watched their units pop above $13 by April 1.

It turns out the market decided it liked the deal, despite the fear of reaching “peak bubble.”

As NYU market professor Scott Galloway noted in March, WeWork has possibilities. “Remote work is an interesting trend, one backed by venture capital dollars,” he said. “And even if there isn’t a significant move in office real estate in cities like New York, new flexibilities will emerge.”

Already, real estate is rebounding, Galloway continued, noting that San Francisco has recovered from its lowest office vacancy rate in 2020.

He also had this to say about WeWork in particular: “At $47 billion, WeWork was overvalued; going public via SPAC at $9 billion, it might be a buy. Prediction: look for WeWork to rise from the ashes of COVID.”

Someday, more than a few investors may look back at the time when the WeWork SPAC presented a risk-free opportunity and wish they had seized the moment and climbed aboard this investment vehicle.

Garrett Baldwin, economist, author and Luckbox editor-at-large, serves as co-host of Lunch Money on the tastytrade network.