SPACs Have Their Moment

Wall Street is spitting out special-purpose acquisition companies at a frenzied pace—but let the buyer beware

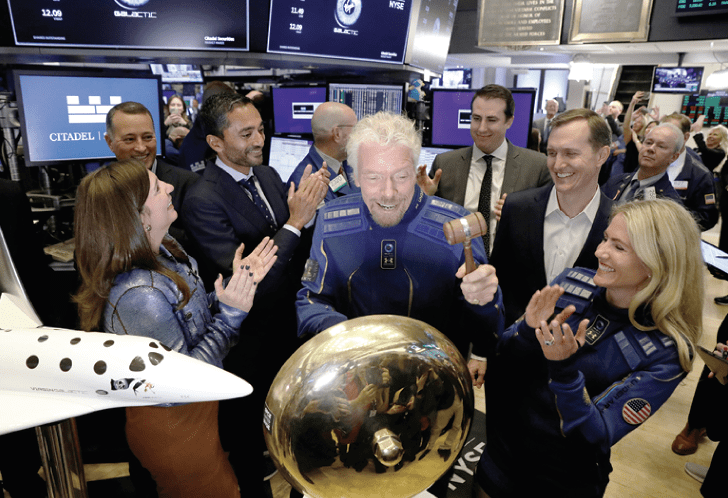

By now, nearly everyone who’s interested in finance has heard of SPACs. They’re the special-purpose acquisition companies typically led by someone with a familiar name—perhaps a well-known fund manager or even a famous athlete.

Those famous or nearly famous people fund their SPACs with initial public offerings (IPOs). But the companies they’re launching don’t have any fixed assets or products to sell. Think of them as publicly traded piles of cash. They’re blank-check companies created to buy something else.

Investors contribute money to a SPAC, which puts the funds into a trust to acquire one or more businesses. But here’s the catch: If a specified period of time passes without an acquisition, or the acquired company doesn’t meet an investor’s standards, then the investor can get the funds back.

Think of SPACs as synthetic convertible bonds. They’re an investment vehicle that offers the upside convexity of equities and the downside protection of a bond backed by the credit of the issuing company.

SPAC frenzy

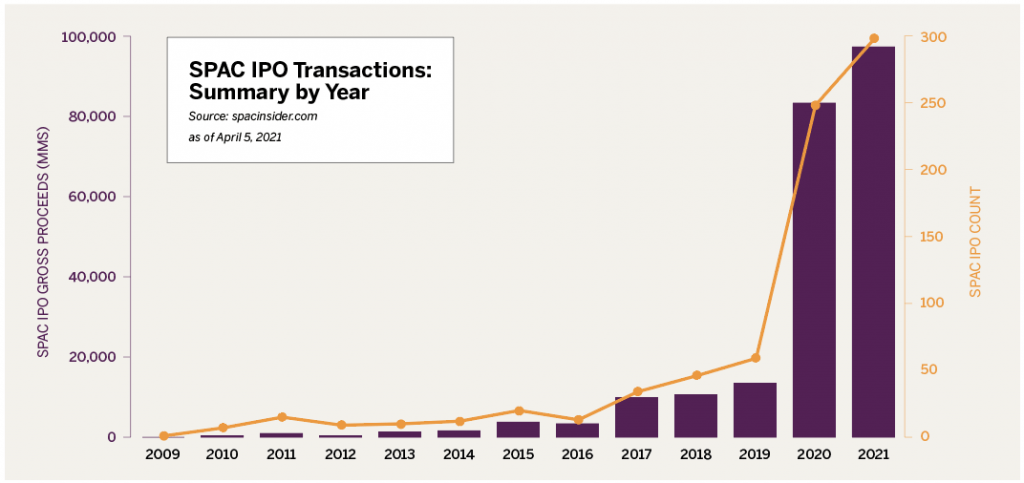

SPAC formation reached an all-time high last year, and it’s continuing at a breakneck pace. Some consider them the ideal investment vehicle in an era of zero interest rates.

In 2009, just one SPAC was navigating the deal process, and it was worth $36 million. By 2018, that number stood at 46. At the end of 2020, 254 SPACs worth $82 billion were operating. Thus far in 2021, 213 aspiring SPACs have filed for an IPO while another 269 are searching for acquisitions, bringing the total to 483 as of March 18.

Why not an IPO?

SPACs serve as reverse-IPOs. Instead of an established private company raising funds by going public, a SPAC operates as a shell entity that’s already raised funds and is looking to bring a private company public.

The IPO process requires a roadshow that lasts several months and includes scrutiny of financial information, but the SPAC process does not. On the day of listing, SPACs are being filled, on average, within an hour of the open, but the average IPO is not seeing fill day-of until at least noon prior to trading.

Meanwhile, investors have shifted away from public markets because of better returns in private equity. After a decade of intense private-equity activity, SPACs are a quick way for private equity to exit monetize assets.

The influx of cheap capital and unforeseen levels of fiscal stimulus have curated ample conditions to bring companies public. And after the WeWork IPO debacle, it’s easy to see why Silicon Valley unicorns prefer to go public through SPACs instead of IPOs. In just one month, the value of WeWork plunged from $47 billion to $10 billion, and the IPO was delayed indefinitely.

Recent changes

With the Securities and Exchange Commission bringing greater scrutiny to SPACs these days, regulators have, in a sense, legitimized them as an investment vehicle. After all, as recently as 2015, Goldman Sachs prohibited investments in SPACs. Now, it has two SPACs of its own.

As private equity investors have exited their positions, the SPAC process is proving more efficient over time. From 2003 to 2015, at least 20% of SPACs were liquidated as a result of the principal failing to find a company to acquire. In 2020, less than 10% of SPACs were liquidated.

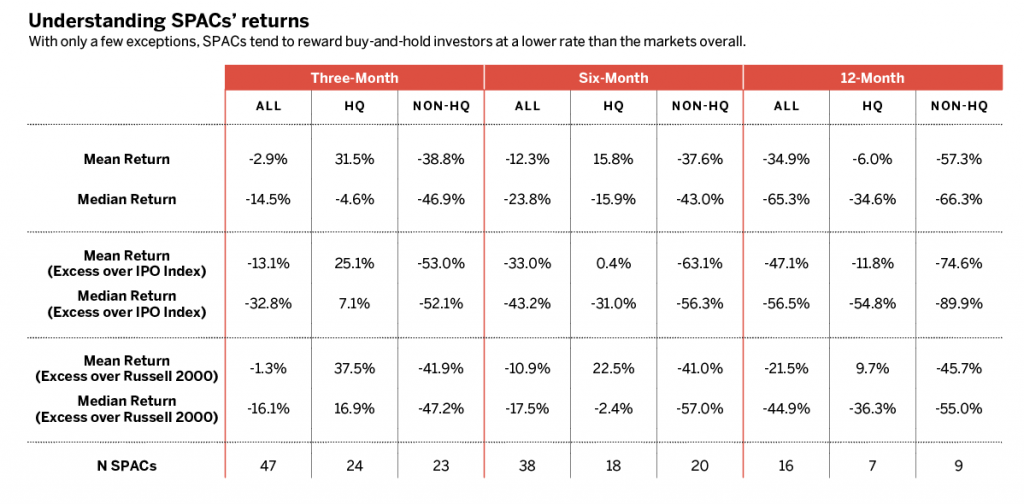

But just because SPACs are popular doesn’t mean they’re the most efficient place to put capital. The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance published a study, A Sober Look at SPACs, in November 2020. The authors dissected the return profiles of SPACs, and the results weren’t friendly:

Although SPACs issue shares for roughly $10 and value their shares at $10 when they merge, by the time of the merger the median SPAC holds cash of just $6.67 per share.

The dilution embedded in SPACs constitutes a cost roughly twice as high as the cost generally attributed to SPACs, even by SPAC skeptics.

When commentators say SPACs are a cheap way to go public, they’re right, but only because SPAC investors are bearing the cost, which makes for an unsustainable situation.

Although some SPACs with high-quality sponsors do better than others, SPAC investors who hold shares at the time of a SPAC’s merger see post-merger share prices drop on average by a third or more.

In fact, three-month, six-month and 12-month returns for both “high quality” and “non-high quality” SPACs are disappointing nearly everywhere one looks. Some observers even call SPACs a bubble, and perhaps that’s true.

It’s the inherent irrationality of investor behavior that gives the bubble characterization some credence. After all, 2021 has been a banner year for SPACs, even though, historically speaking, SPACs underperform the market. As always, buyer beware.

Christopher Vecchio, CFA, is a senior currency strategist for IG Group’s DailyFX, a commodities, equities and forex research firm. @cvecchiofx