The King of SPACs

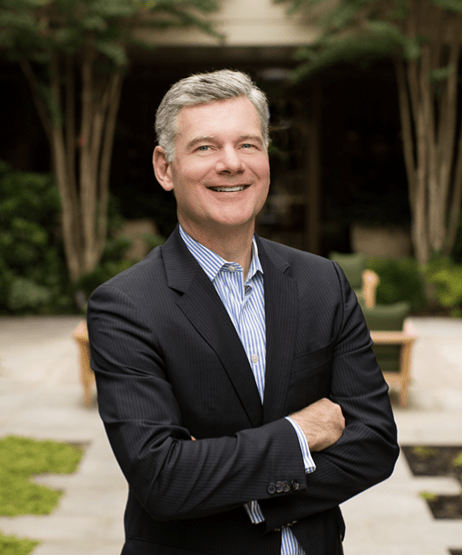

Doug Ellenoff, the founder of one of America’s leading SPAC law firms, explains the wildly popular investment vehicle.

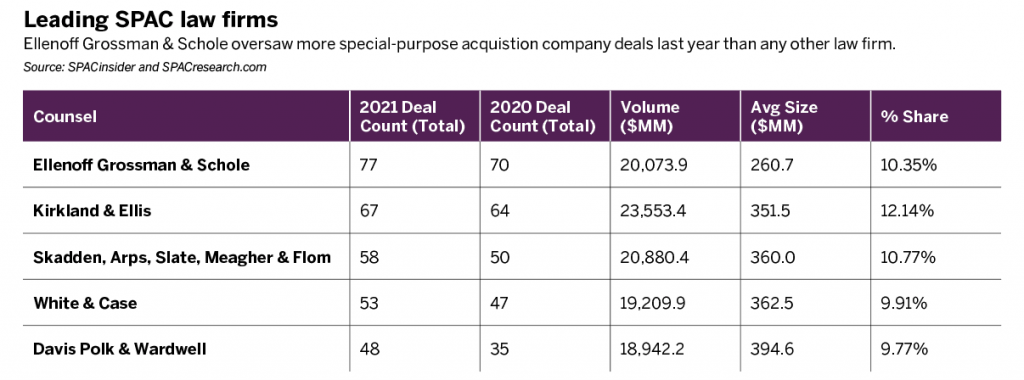

To understand the substantial value of SPACs, or special-purpose acquisition companies, Luckbox ignored the noise and went straight to the source—the law firm of Ellenoff Grossman & Schole. For 25 years, the attorneys there have specialized in SPACs, initial public offerings (IPOs), registered direct/private investment public equity (PIPEs) and reverse mergers.

In the last decade, the firm has engaged in nearly 40% of all new SPACs. It led the SPAC IPO Legal League Tables for 2020 and ranked No. 1 of 17 firms in terms of deal flow. In 2020 alone, the firm worked on 70 SPACs. It has completed at least 325 SPACs over 18 years.

So, they know what they’re talking about.

In this interview, Doug Ellenoff, a founding member of the firm, discusses the misconceptions that cloud the public’s understanding of SPACs, the market incentives that drive investment capital into private vehicles and the factors that make SPACs a favorable strategy for investors.

Let’s start with your business. What’s a law firm’s due diligence process with a SPAC? How do you evaluate prospective clients?

It’s an easy conversation in the SPAC market because you’re attracting established financial players in the private equity or venture world, or executives of significant private or public companies. It doesn’t require a lot of diligence. It’s a bit more complicated when the deals are international and we have to consider the team.

SPACs have become popular even though a stigma was attached to them just 10 or 15 years ago. What’s made SPACs mainstream?

Let me first say I don’t believe the stigma of SPACs is over. We’re certainly in a better place. But if the private companies that went public in the last eight months fall on hard times, I’m confident those who are predisposed to dislike SPACs will point fingers again. It’s a default reflex to find fault in SPACs.

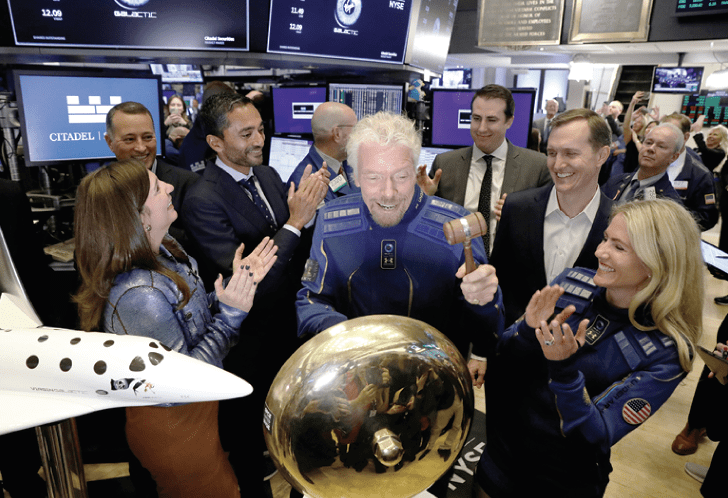

The growth of SPACs didn’t happen overnight with Virgin Galactic or Bill Ackman or DraftKings. It was the hard work of lawyers, accountants, investment bankers and principals who iterated the program coming into 2020. Those successes—with fewer failures in a bull market—admittedly led to a dissipation of the concern and negativity that regulators and law firms had put out in the early years.

When Virgin Galactic and then Bill Ackman had success, those who had been monitoring the program with skepticism started scratching their heads and thinking “I don’t understand why people were saying such negative things about SPACs.”

Is Bill Ackman’s decision to waive the 20% SPAC sponsor fee important to the shift in perception?

Not in the slightest. It makes for an interesting narrative, but nobody’s followed suit. I think that’s telling.

Is there margin pressure on that fee?

It’s not whether or not it’s appropriate to ask for 20% upfront, fully disclosed. What is being debated at the time of the pricing of the

PIPE and the acquisition, legitimately, are the economic realities of SPACs being satisfied to the degree that the sponsor should get to hold onto the entirety of the 20%.

I don’t have a problem with Bill Ackman’s structure. He’s not novel if you go back a decade ago when Goldman first tried to come to the market with a deal and had a unique structure. Before that, we had other structures. People will tinker around the edges to make this statement of greater harmony of interest among the sponsors, targets and investors. That’s a positive objective.

You said it’s a default reflex to find fault with SPACs. Financial media tend to oversimplify everything: SPACs are good, SPACs are bad, it’s a bubble. Does this vehicle get fair treatment?

The media played into the hands of the narrative of the early 2000s. At the time, many people didn’t have an interest in the program. These people weren’t concerned with giving an honest appraisal. The media followed their lead. If you look at every article between 2000 and 2010, most start with negativity and concern.

What’s the top SPAC misconception among investors and the media?

Most people don’t understand how SPAC business combinations get consummated. And I don’t know how people write about SPACs and fail to understand the redemption clause.

Would you walk us through that consummation process?

Sure. If I raised $250 million, I am now on the hunt. I find a private, pre-revenue company. Maybe it’s in biotech or tech. I want to do a deal with that entity. That $250 million that I raised is still subject to redemption.

I say to the target that the $250 million is subject to redemption, but I want to help de-risk the transaction. We both know the deal will get done. We sign a letter of intent with valuation terms and the amount of cash the target company requires. In short order, we market a confidentially marketed PIPE—not to retail investors, but institutional investors—the most sophisticated portfolio managers at the largest U.S. institutions. Then we say to them, “Do you like this deal? Do you like the valuation? Are you willing to put up capital to help de-risk this transaction?” They then provide their opinion. This does not involve an amorphous group of investors.

It involves managers who understand EVs (electric vehicles) or biotech companies and portfolio managers who typically have experience in these companies. Once they say they’re in in enough volume, then the transaction proceeds through the diligence process, which is IPO-like, and whether or not that’s business, legal or financial due diligence. Then we sign all the documentation. And that’s all still confidential. Then we publicly announce it.

Once we publicly announce it, if the stock goes up, investors still have the right of redemption up until closing after the shareholder vote.

They can redeem. They can vote. If the stock goes up, there’s no incentive for them to redeem. They could just sell into the open market and take the profits.

Why do SPACs exist?

When I started practicing law 30-plus years ago, there were 10,000 publicly traded companies in the U.S. That number’s been cut in half. Why? More intentionally designed disincentives to be public. How is that a good societal policy?

Now, the thesis was that we don’t want risky companies in the market. Where’ve they gone? They went to venture capital. Markets don’t stop. They mutate. So, you had more private equity firms, more venture capital firms and thousands of portfolio companies in the private markets.

Today, we have larger IPOs but fewer of them. Our thesis has always been that the SPAC market enables qualified sponsors who understand the public markets and industries, and are equally capable of identifying interesting companies or opportunities to take public.

Are you concerned about SPACs that double or even go to $60 before a deal announcement?

How can I not be? That creates other regulatory concerns. I never want as a professional to feel someone is taking advantage of retail investors. It’s not my DNA, but we have a federal system that says as long as you have access to full and fair disclosure, which they do, they can make an informed investment decision.

It’s also not my client’s responsibility to do a brokerage firm’s work and ensure they’re properly helping clients.

How are celebrities influencing these deals?

My basic feeling is, like all sponsors, you need a range of competencies and expertise. It’s not akin to somebody launching a digital asset and slapping some celebrity’s name on it just to create awareness. There’s substance under the hood here for each of these professional athletes.

We’re trying to incent private companies to do business with us. And the value proposition, when it works, is I’m not just going to go to any SPAC as the lowest-cost way and means to get public. But I want to do business with people who can advance my opportunity in a way that I can’t.

What advice would you give investors who are considering SPACs?

The SPAC market has facilitated the creation of many new investment opportunities that—depending on an investor’s risk profile and appetite—may or may not be appropriate for a portion of their portfolio. That’s recognizing that portfolio theory does not suggest overweighting riskier growth opportunities—whether that’s a SPAC or otherwise—disproportionately as a portion of their portfolio.

As I’ve said, I’m fine with what’s going on now, so long as people who study it recognize that the stock market has proven an appetite for private equity deals and venture deals. And the mechanism itself is agnostic—it’s what investors want. That’s what people should be focusing on. Why is it that there’s such a desperate scramble to find interesting opportunities in the public markets? Investors can’t access the same sort of opportunities they want to support in the private markets.

What question should people ask instead of getting lost in a conversation about the supposed SPAC bubble?

“Why is the stock market useful?” Assuming that there’s a positive answer for that, why isn’t there a conversation around what we do to improve it? If there is a need to improve it, there are always programs that develop slowly over time. Just like the introduction of the PIPE as the permanent capital funding mechanism for the business combination post-2012 is how we got there. And the SPAC market is responding to the ills of other means of finance. It should be embraced and encouraged, as opposed to potentially stigmatized and derided.

The conversation was edited lightly for style and brevity.