The March of Hype

As technology advances, each generation gets its own version of hyperbolic advertising, promotion and manipulation. That’s both good and bad.

Hype resides in the eye of the beholder. while some consider it exaggeration or even deception, others define it as anything that attracts the public’s attention.

Viewed as the latter, hype can promote a product, personality or idea. But at the extremes, it can work as a powerful force for good or for evil.

Hype can seem like something new, but it’s been at work since time immemorial. Even in the Stone Age, news could spread by word of mouth faster than a person could walk.

Each step along the technology trail has increased the speed and power of hype. Early on, drums carried coded messages more quickly and accurately than the chain of gossip could deliver the news.

By the ninth century, woodblock printing was feeding the hype machine in China. Koreans were using movable type to print books in the 13th century.

In Germany, Johannes Gutenberg cranked out his first Bible in 1436 on a screw-type wine press that applied pressure evenly on inked metal type. In three years, he produced 200 copies of the Bible.

Compared with hand copying, the speed and accuracy of the printing press was unprecedented. But no one really knew what to do with so many Bibles, so most sat unused and Gutenberg died penniless.

But not before he helped end the Middle Ages, played a vital role in ushering in the modern era and prepared the world for an unprecedented rush of hype.

Less than a century later, Martin Luther became the world’s first best-selling author. Some 5,000 copies of his translation of the New Testament into German sold between 1518 and 1525.

From there, technology created a whirlwind of hype. The telegraph, developed in the 1830s and 1840s by Samuel F.B. Morse and other inventors, transmitted dots and dashes over electrical wires.

Guglielmo Marconi invented the radio when he sent a wireless Morse Code message through thin air in 1895. By the 1920s, Lee de Forest was turning radio into a purveyor of entertainment and hype, and Hollywood attached sound to movies.

A still image transmitted over wires in 1862 marked an important milestone on the long road to television, the medium that would eventually do so much to advance the cause of hype. World War II slowed the TV’s progress, but it exploded in popularity in the postwar world from the late ’40s to the mid-’50s.

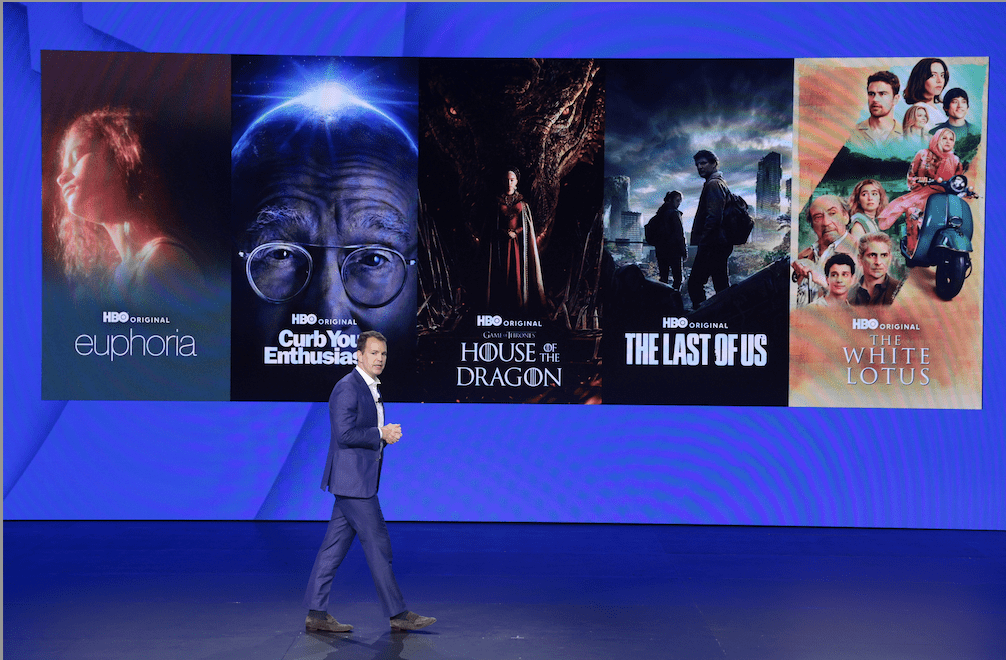

For a few years, it may have seemed to many that television had brought hype to its pinnacle. But in 1983, an even more powerful engine of hype was born: the internet.

And the internet gave rise to the Golden Age of Social Media, a period often thought to have ended in about 2012, which brings the discussion more or less to the present day—an era marked by social media’s slide into commercialism and a longing for the as yet unrealized metaverse, an alternative digitally unreality.

Pushing products

The public has always been willing to accept—if not necessarily embrace—a certain amount of promotional hype.

In one example, polling during the Golden Age of Radio in the 1930s and 1940s indicated a majority of Americans agreed that listening to ads in exchange for news and entertainment constituted a “fair deal.”

But advertisers don’t just provide information on products. In print, on the airwaves and through the internet they manipulate audiences by portraying their wares as the ticket to self-esteem, social acceptance and the good life. Ads create a “need.”

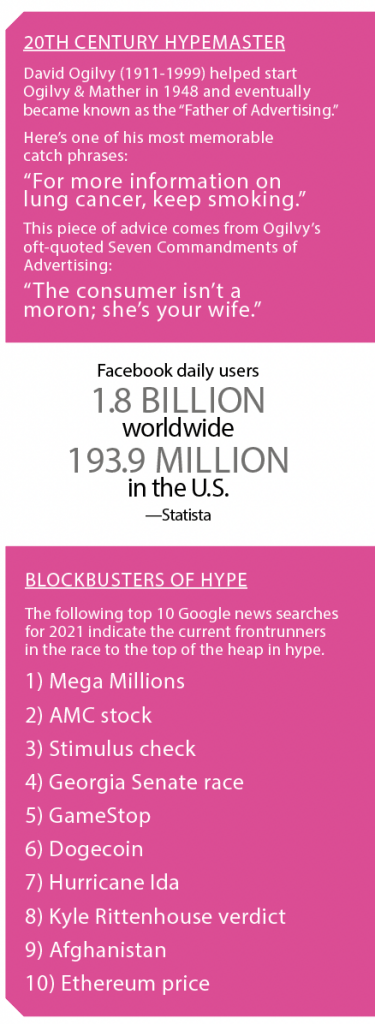

That process gave rise to so many 20th century icons. Think of the hucksters for processed foods that have ranged from Tony the Tiger to the Jolly Green Giant, or fictional but dedicated public servants like Smokey the Bear.

In the 21st century, the task of moving consumers to buy their way to happiness is beginning to shift to social media influencers. They’re the people who have established themselves as experts on a particular topic and go online to post their thoughts to large audiences of followers.

Mega influencers with more than a million followers on a single social medium have begun to employ agents who negotiate deals that can net them a fee of a million dollars for a single post.

Rankings of the most popular or most effective influencers list names that often come from the ranks of fashion mavens and entertainers. Some have amassed tens of millions of followers.

Micro influencers, whose followers number only in the thousands, promote brands for free if they fit the theme.

Nano influencers have only a small number of followers, but their product endorsements can prove powerful because of the devotion of their fan bases.

Mega, nano or something in between, today’s influencers have plenty of places to ply their trade. A list of the top social media would have to include Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Pinterest, Reddit, Twitter and Quora.

Legions of consumers are responding. In fact, the number of people using social media has reached 3.4 billion, or nearly half the inhabitants of the planet.

But “influencer marketing” on social media takes its place among five strategies that MIT professor Sinan Aral has identified in his book The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health—And How We Must Adapt. The machine in the title is what he also calls the “social media industrial complex.”

The Hype Machine

Aral’s five strategies for marketing the “hypersocialized” world in and around social media are:

Network Targeting—It works well to aim social media messages at an individual, but it’s even more accurate to include information from the subject’s associates because people seek friends with similar interests.

Referral Marketing—Network connections don’t just predict preferences. They also influence preferences, so companies like Uber, Tesla and Airbnb have used personalized word-of-mouth referral programs and incentives to grow their businesses.

Social Advertising—Seeing a friend’s preferences influences one’s own preferences. Facebook exploited that tendency in a get-out-the-vote campaign by showing the faces of friends who had voted.

Viral Design—The first three strategies apply to products or ideas that already exist. Viral design creates something new that’s calculated to make people share it with friends.

Influencer Marketing—Influencers can convince their social media followers to follow a trend or buy a product. They can use their leadership to pursue commercial ends or to push the public toward good or evil pursuits.

Personal hype

While Aral writes about social media as a machine for creating hype, another author, Michael F. Schein, addresses hype on a more personal level in The Hype Handbook.

Schein was working as a freelance copywriter and found he had to learn to promote himself to get assignments. Eventually, he became so good at hype that he abandoned the writing life to become a hype consultant to business executives.

In his book, Schein provides 12 “secrets” to successful hype, but he notes that three of them carry the most weight:

Make War, Not Love—People like to oppose something. Thus, they’ll pay attention to a hype seeker who attacks an idea or competitor.

Piggy Backing—Successful hypesters make whatever they’re doing seem like a grassroots movement. And they nurture strong circles of well-placed connections.

Protect Your Packaging—To get the public to buy a product, follow a person or consider an idea, would-be hype masters should block out the noise by cleansing their presentation of everything extraneous.

For good or ill

However one approaches hype, the result can work for the benefit or detriment of society and the individual.

Schein offers an example of how murky the intersection between good and evil can become when hype comes into play. He said Warren Buffett and the late Charles Manson have both cited the importance of the same tenet from Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People.

The famed investor and the cult leader accomplished their goals by employing Carnegie’s 16th principle of knowing how to “let the other person feel that the idea is his or hers.”

Meanwhile, Aral takes the macro view. He told Luckbox he views hype and its newest medium, social media, as offering society two paths: “promise and peril.”

“Social media could deliver an incredible wave of productivity, innovation, social welfare, democratization, equality, health, positivity, unity, and progress,” he said in his book.

But it’s up to society to realize that potential. “If left unchecked, it will deliver death blows to our democracies, our economies, and our public health,” he maintained. “Today we are at a crossroads of these realities.”

Victim of His Own Hype?

Mark Zuckerbergmay be committing the ultimate marketing sin of believing his own hype. At least that’s the theory of someone who should know—Michael F. Schein, the author of The Hype Handbook.

“He may be thinking of himself as a godlike creator of worlds,” Schein says of Zuckerberg. “He thinks he’s creating a science fiction utopia.”

Zuckerberg’s faith in that utopia runs so deep that he’s renamed his company Meta, short for the metaverse, an alternative unreality that techies are creating on the internet.

“Wall Street isn’t buying it,” Schein says of Meta’s devotion to the metaverse. That’s partly because no one’s exactly sure what the metaverse will be or when it will arrive.

To make matters worse, Facebook meanwhile lost 500,000 daily users in the last three months of 2021, and the company projected earnings of $27 billion to $29 billion in the first quarter of this year, short of the $30 billion analysts had expected.

Add up the shortcomings, and Meta Platforms (FB) has lost $251 billion in value, the biggest stock market downturn in history. It was trading at $207.60 at press time, down 85% from its highest-ever closing price of $382.18 on Sept. 7, 2021.

A big part of the problem lies in Zuckerberg’s risky headlong plunge into the metaverse, Schein maintains. That transformational approach differs greatly from the wildly successful incremental history of Zuckerberg’s Facebook.

Facebook began in 2003 as Face Mash, and access was limited to students at Harvard. It became TheFacebook in 2004 as it was spreading to other Ivy League schools. It wasn’t until 2006 that it grew into something resembling today’s Facebook and became available to the general public.