Amazon Primed

Public enemy No. 1, or Wall Street hero? Either way, odds say Amazon will dominate competitors for a long time to come.

Consider the great accomplishments of humankind—harnessing fire, inventing the wheel, discovering electricity, achieving flight. Let’s add Amazon to that list. Amazon (AMZN) didn’t invent the internet, or even online shopping, but it used the power of technology to reshape human habits and created $1.7 trillion in market value in the process. Amazon became a refuge during COVID-19. It saves consumers time and money. It introduces products no one knew existed. After all, necessity is the mother of invention.

Amazon’s runaway success invited the world to hang a “kick me” sign on its back. It’s not the biggest company in the world, but it’s near the top. And it’s the biggest company that’s so well known to the public. Americans don’t see Apple trucks driving down the street or keep an eye on the driveway to see if Google delivered a package. So, Amazon becomes a convenient, personalized target for anyone with a gripe against capitalism.

On the other hand, Amazon can bring scorn down upon itself simply by implementing a business model. It angers conservatives by booting Parler off of Amazon Web Services. It enrages liberals by quashing attempts at unionization. It offends small businesses by stealing customers and big businesses by investing big dollars to compete in their industries. In that way, Amazon seems like a Bizarro Santa Claus, delivering something for everyone to hate—despite bringing jobs to the unemployed and next-day delivery to insatiable consumers. It takes products to a global marketplace for sellers willing to play by its rules.

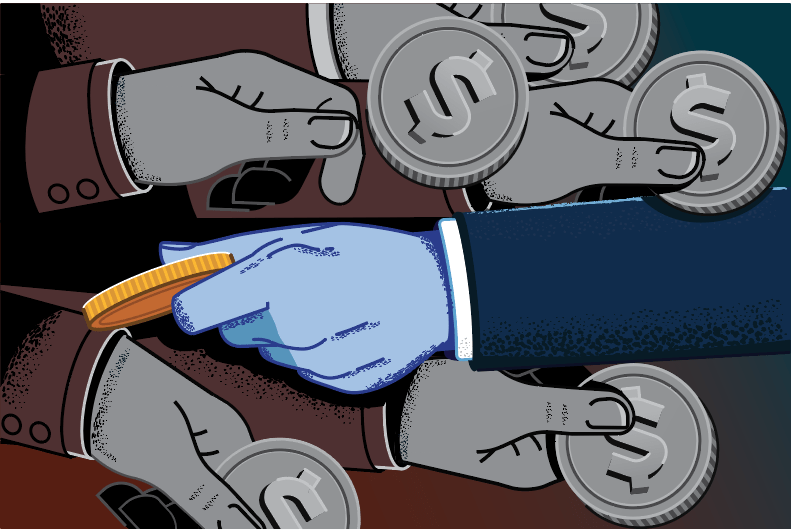

Wall Street loves Amazon, giving it a valuation that far exceeds its direct retail competitors like Alibaba (BABA), Walmart (WMT), Costco (COST) and Target (TGT). Amazon’s price-to-earnings ratio is 81, while Alibaba’s is 26, Walmart’s is 29, Costco’s is 37 and Target’s is 23. That, in turn, makes Amazon’s market cap much higher than those of the other companies, too. Wall Street might respond by citing Amazon’s lobbying power in Washington, praising its superior website, and noting its diversification into strong performers like the cloud and streaming video. But the Normal Deviate isn’t about fundamental analysis and doesn’t give a damn about what Wall Street thinks. It’s about probabilities and different ways to think about them.

Amazon is dominant now—no question. And it’s a very valuable company. But what if those other companies begin to outperform? Could they someday have a market cap equal to Amazon’s?

To answer that question, let’s break into the probability formula and look at the part that models the random walk, or Brownian motion.

(r—2/2)t

The “ ” is the volatility of the stock, “t” stands for how long into the future the probability is being evaluated and “r” is an interest rate, usually a current benchmark risk-free rate. That rate is the expected return of the stock or asset that is equal to at least the rate on a Treasury bill, for example. If there were no possibility of earning at least that risk-free return on a risky asset, then there would be no need to invest in it instead of a T-bill. Those variables combine in the formula to describe a stock behavior that rises by “r” but gets knocked down by “ .” That’s the random up and down price action investors see most of the time.

But mathematically, that “r” can be set to any expected growth rate in the stock. It simply makes the theoretical stock price increase by that rate over time. Think the stock will grow 10%? Stick .10 in the formula for “r.” Keep in mind that it’s just a guess. A trader might not want to do this for trading purposes because it will make all options prices and probabilities far off from current market values. But it’s fine to use it to see a theoretical probability of a stock reaching a higher price if it grows by a certain rate.

The test is to see if the market capitalizations (the number of shares outstanding times the stock price) of Amazon’s competitors might reach its market cap in the future. There are three big assumptions. First, volatility stays at its current level. Second, the number of shares outstanding doesn’t change. Third, the growth rates are constant. Let’s also assume that Amazon grows by 10% and Alibaba, Walmart, Costco and Target grow by 20%—twice as much as Amazon—every year for five years.

Now, let’s see the probabilities for Amazon’s competitors to catch up.

Alibaba has the best chance, with a 16% probability of having a price high enough to make its market cap equal to Amazon’s. Walmart is next, with 2%. And the probabilities of both Costco and Target reaching Amazon’s market cap are less than 1%.

OK, let’s take it out 10 years, with Amazon growing at 10% a year and the other stocks growing at 20%. Alibaba has a 29% probability of reaching Amazon’s value, Walmart has a 17% probability, and both Costco and Target have a 1% probability. Looks like Amazon doesn’t have much to worry about for quite some time.

Now, what happens in the future is anybody’s guess. But regardless of whether one loves or hates Amazon, it’s likely to continue to dominate market cap vis-à-vis its competitors. That’s not to say its competitors’ stock prices won’t rally, but they probably won’t rally enough to make them a threat.

Tom Preston, Luckbox features editor, is the purveyor of all things probability-based and the poster boy for a standard normal deviate. @fittypercent