Long Call Speculation

Paying a fee to lock in a price

Buying a long call option is like saving a coupon for a rainy day.

Let’s say a clothing store sells rain jackets. Shoppers aren’t certain if the upcoming season will be rainy or not, so they don’t want to risk buying a $100 jacket and not using it. If the store offers a $5 coupon that guarantees the $100 purchase price, they can wait for a month to decide if they’ll buy the jacket.

Now, suppose that two weeks pass and it rains nonstop. People are flocking to the store to buy rain jackets, so the manager raises the price to $120. Customers with coupons can still buy the rain jacket for $100 instead of the inflated price of $120.

In the opposite scenario—it doesn’t rain for weeks and no one needs a rain jacket—coupon holders can let them expire and just lose $5 instead of the $100 they would have lost if they had bought the jacket and not used it.

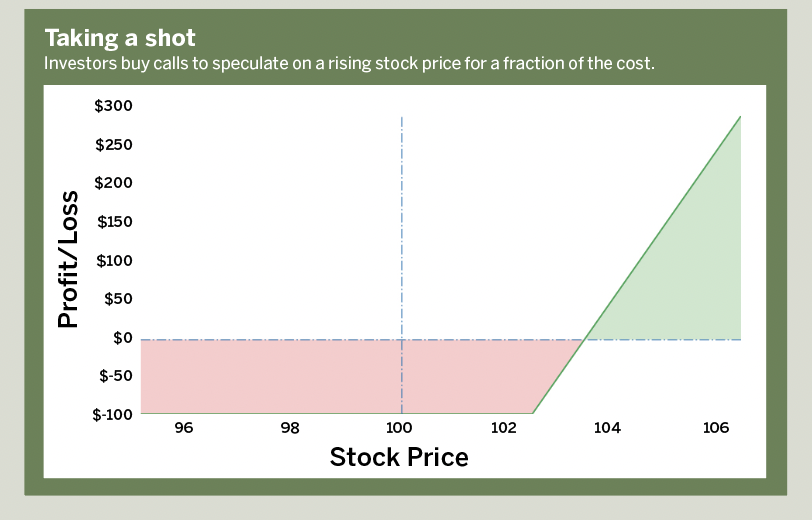

In finance, a long call works in a similar fashion. This options strategy of buying a single call option gives the owner the right to buy 100 shares of a stock at a designated price on or before a future date. The designated price is the option’s strike price and that future date is the expiration date.

To buy a long call, the owner pays a premium to the seller. Traders use long calls because they believe the stock will increase before the expiration date but don’t want to buy the shares initially. If the stock increases in price, the value of the long call has a similar increase. When investors are satisfied with their gain, they can sell the call to lock in the profit.

Eddie Rajcevic, a member of the tastytrade research team, serves as co-host of the network’s Crypto Corner and Crypto Concepts programs. @erajcevic11