An Election Up for Grabs?

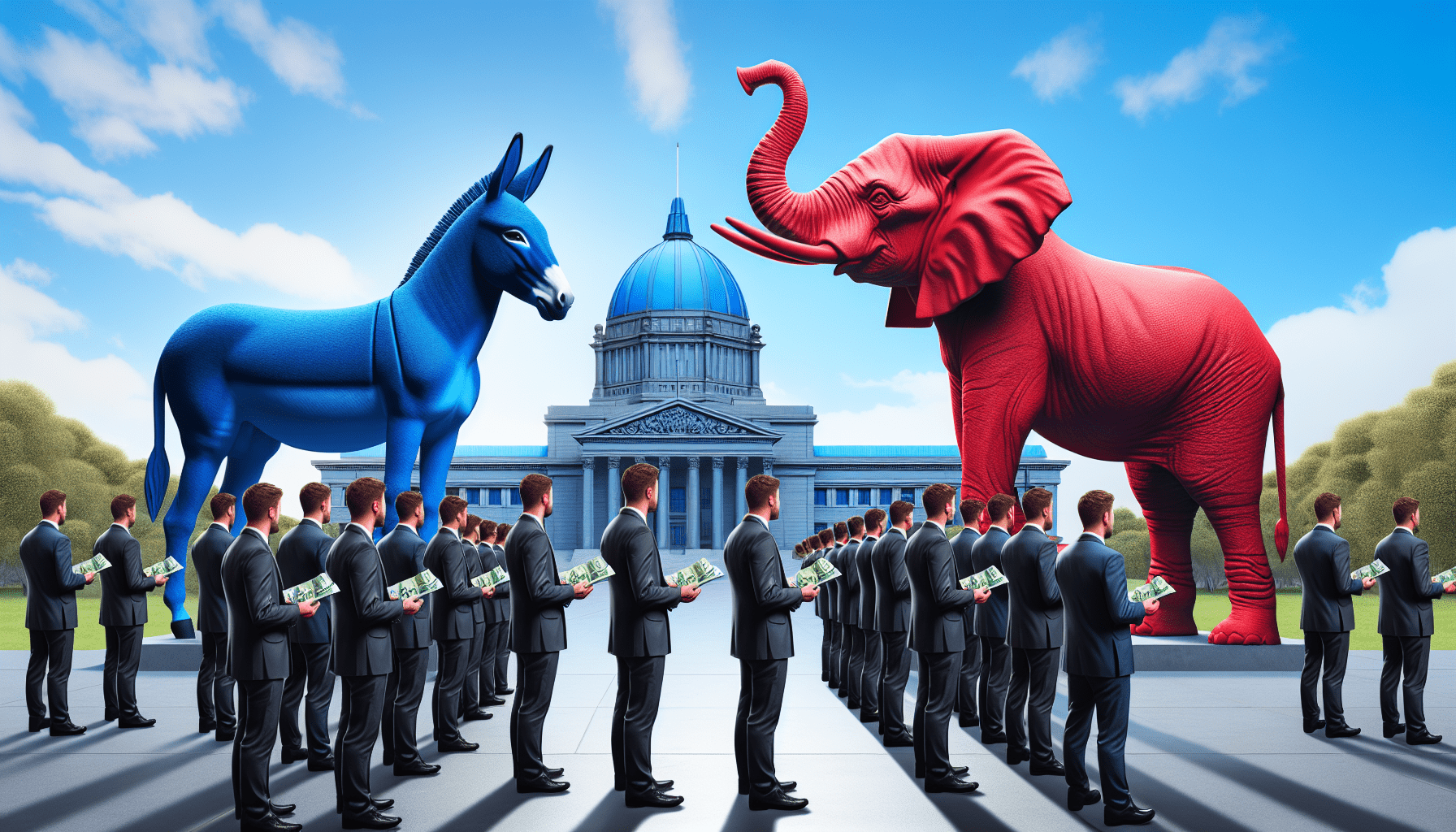

Two methods of foretelling the outcome of presidential elections—both of them long-established and well-regarded—are coming up with different predictions this cycle. One favors Trump and the other picks Biden.

Two scholars noted for their prowess at predicting the winners of presidential elections—including Donald Trump’s generally unanticipated Electoral College victory in 2016—are parting ways this year. One’s betting on a win by former Vice President Joe Biden, and the other’s picking President Donald Trump for another term. Let’s parse the details.w

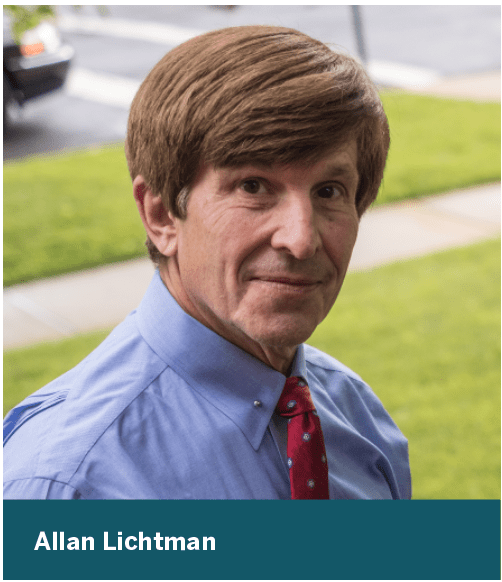

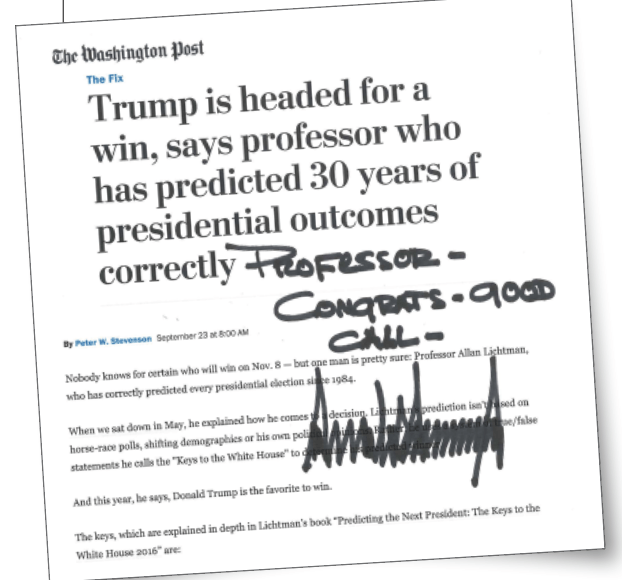

Allan Lichtman, a professor of history at The American University in Washington, D.C., says he’s accurately foretold the outcome of every presidential contest since 1984, even though some dispute the veracity of a couple of his prognostications. This time, he’s counting on a win for Biden but hasn’t estimated the margin of victory.

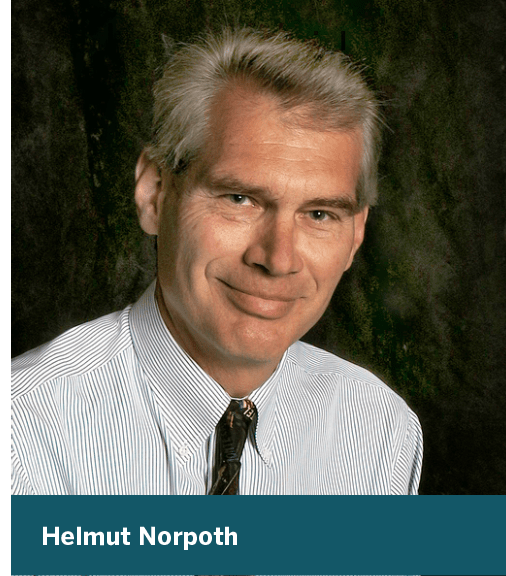

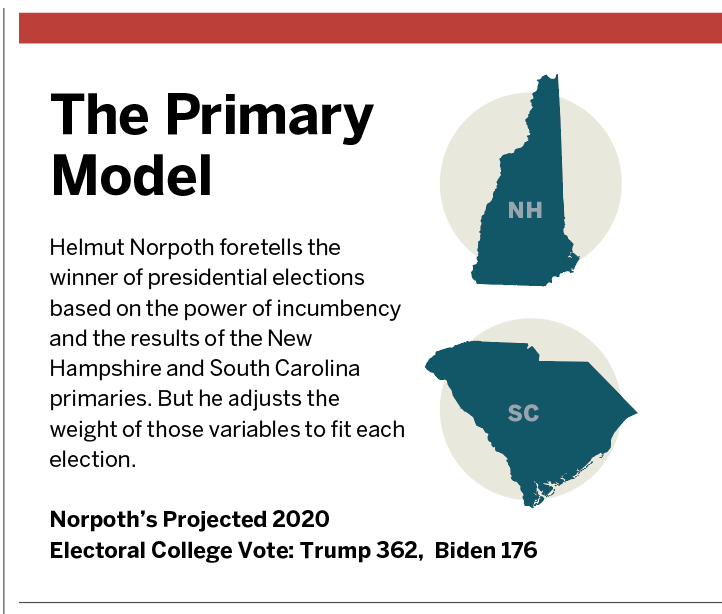

Helmut Norpoth, a professor of political science at Stony Brook University on New York’s Long Island, contends that he’s been right about the results of five of the last six presidential contests. He’s calling this one for Trump, giving him a 91% chance of winning with 362 Electoral College votes to Biden’s 176.

Neither soothsayer waits around to see how the candidates will fare in the debates or in polls. Lichtman declared on Aug. 5 that Biden would prevail, and Norpoth announced March 2 that Trump would win re-election.

Despite the split decision, both scholars seemed adamant about the reliability of their predictions when they discussed the upcoming election in interviews with Luckbox.

“In late 2019, Trump was looking pretty good,” Lichtman maintains. “Then we got hit with the pandemic, the recession and the cries for social and racial justice. It’s a strong prediction for Biden.”

“It looks like a landslide,” for Trump in the Electoral College vote, even if he loses the popular vote again, according to Norpoth. “These predictions are written in stone,” he asserted. “I’m stuck. I can’t get out of it.”

Method to their madness

Both academicians have developed models for predicting the outcome of presidential contests. Lichtman worked with Russian seismologist Vladimir Keilis-Bork, an expert on earthquake prediction, to develop the Keys to the White House Model in 1981. Norpoth came up with the Primary Model in the early-to-mid ‘90s, in time to forecast the winner of the 1996 election.

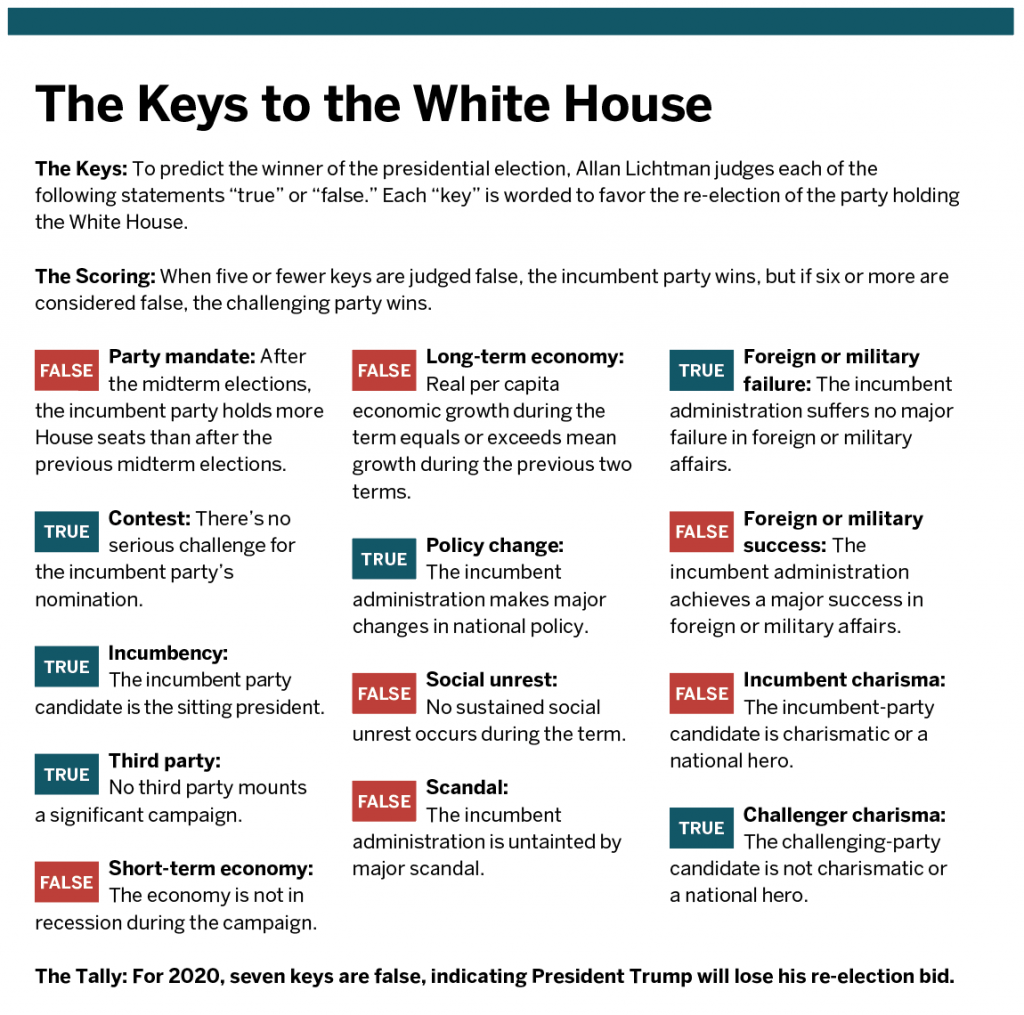

Lichtman’s model hinges on true-false answers to 13 “keys” that measure the power of factors that include incumbency, policy, scandal, charisma, social unrest, foreign affairs and the economy in the near and short terms. The incumbent party is expected to win re-election if five or fewer keys are false. Lichtman believes seven are false this cycle, meaning that Biden will ascend to the highest office in the land.

There’s a good reason why Trump will fall short, according to Lichtman. “He didn’t recognize the fundamental insight behind the keys, which is that governing, not campaigning, counts,” the professor says. “And instead of dealing substantively with the challenges, he reverted to his challenger playbook of 2016 and tried to talk his way out of them. It didn’t work.”

Norpoth says most prognosticators base models on the performance of the economy or the approval ratings of candidates based on polling. He wanted to find another niche and thus predicates his model on two factors—whether the party in power seems primed to lose control and which candidate did better in the primaries.

So Norpoth used time-series analysis to analyze election results and discovered that the numbers back up the conventional wisdom that the political pendulum swings back and forth between left and right. That research showed Bill Clinton would be re-elected despite the fact that many considered him “toast” after the beating the Democrats sustained in the ’94 midterm elections.

That prediction came true, but the methodology provided only a 60% level of certainty. Norpoth wanted to strengthen his model and came up with the idea of tracking primaries, an approach none of his colleagues seemed to use. He began by using all of the primaries to establish patterns but found that beginning in 1952 the New Hampshire primary has been a nearly perfect predictor. For example, sitting presidents Harry S. Truman, Lyndon Johnson and Jimmy Carter turned in weak performances in New Hampshire and didn’t go on to second terms. So Norpoth uses the New Hampshire results to shape his predictions but has also added the South Carolina primary for better racial balance.

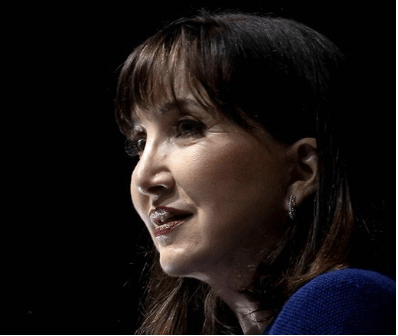

“Trump is a great showman, but he’s not one of those once-in-a-generation, broadly appealing candidates like Ronald Reagan.”

Historical reach

Lichtman’s Keys Model applies pattern-recognition methodology used in geophysics to data for American presidential elections as far back as 1860, the first contest with a four-year record of competition between Republicans and Democrats.

Defining the keys narrowly prevents undue subjectivity from creeping into the process of judging a key true or false. For example, Lichtman defines an incumbent party nominating process as contested if the losing candidates secure a combined total of at least one-third of the delegates.

History also guides judgments in the Keys Model. To qualify as charismatic, for instance, a candidate has to measure up to Ronald Reagan, John F. Kennedy and Theodore Roosevelt, Lichtman says.

Norpoth likewise relies on history to make his projections. When he studied the 1912 election he saw that former President Teddy Roosevelt had badly beaten sitting president William Howard Taft in the primaries. Imagine, Northpoth thought to himself, a sitting president losing in the primaries! But the delegates to the Republican convention decided to run Taft anyway. Meanwhile, Democrat Woodrow Wilson won the primaries on the other side and captured the nomination. So a primary loser and a primary winner faced off with Wilson emerging victorious. Roosevelt cast a shadow on the model by running as a third-party candidate, but in Norpoth’s view, the election verified the Primary Model.

The Primary Model generates numbers that coincide with the actual results of 25 of the 27 elections conducted since 1912. The first exception occurred in 1960, an election some believe Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley stole for Democratic Sen. John F. Kennedy by stuffing the city’s ballot boxes. The second was in 2000, an election some insist Republican operatives stole for George W. Bush by tainting the Florida recount and contesting the outcome all the way to the predominantly conservative U.S. Supreme Court.

Where models fall short

Some would dispute Lichtman’s claim that he’s compiled a perfect string of predictions because he erroneously projected that Trump would win the popular vote in 2016. The professor says he now disregards the popular vote because the Democrats will win it anytime the totals are close and neither party can carry off a landslide.

In 2000, Lichtman and Norpoth both bet on Gore, who won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College vote. Although the professors made the same predictions, Lichtman counts his as correct while Norpoth concedes his was wrong.

The question of subjectivity arises with the keys, too. The key that critics find most subjective has been the charisma key, but Lichtman has awarded it to neither Trump nor Biden. “Joe Biden’s a good guy who can make a great speech, but he’s still not a John F. Kennedy or Barack Obama,” he opines. “Trump is not one of those once-in-a-generation, broadly appealing candidates like Ronald Reagan. Trump’s a great showman, but he appeals only to a narrow slice of the electorate.”

Although the 13 Keys Model isn’t perfect, it’s very good, Lichtman maintains. It’s produced consistent results when applied to elections dating back to “the horse and buggy days,” he contends. What’s more, professional forecasters have concluded that the best predictions result from combining judgments with quantifiable factors, he notes.