What Young Voters Want

Ballots cast by voters under age 30 matter, and here’s how they could influence this election cycle.

By the time Luis Aguilar was 7 years old, he was already serving as a translator to help his immigrant parents and grandparents vote in elections in California’s Central Valley.

“With my grandma, we’d walk to the polling place, which was miles away,” Aguilar recalled. “I’d have to tell her, ‘This is who we’re voting for. This is what you have to do.’”

That experience helped prepare him for his current role as a team leader at HeadCount, a nonprofit organization that registers young voters at concerts and music festivals.

It also gave him a keen sense of the importance of casting a ballot.

“I’ve seen that growing up in a space that is so dependent on agriculture and migrant farmers that there was a need for representation in our leaders,” he said.

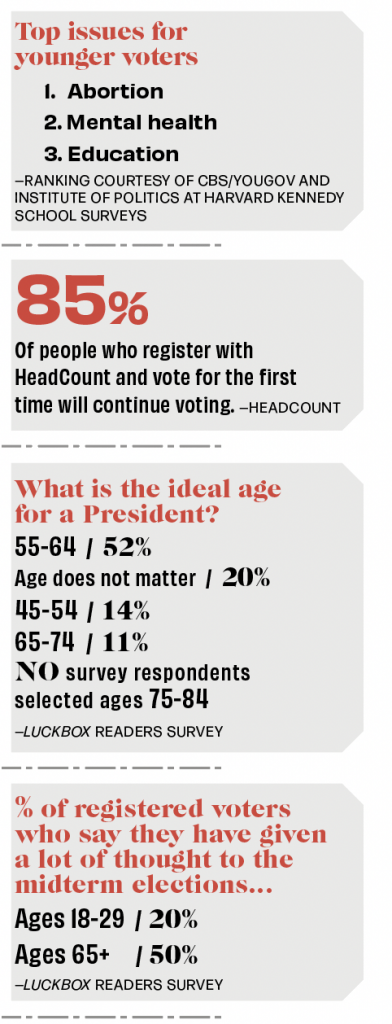

But many young people don’t share Aguilar’s faith in the importance of politics. Polls reveal the No. 1 reason they don’t participate in elections is they feel their vote doesn’t matter.

Still, turnout is increasing among voters ages 18-29. Fifty percent of the age group voted in the 2020 presidential election, an 11-point increase from 39% in 2016, according to The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). The election of 2020 had “one of the highest rates of youth electoral participation since the voting age was lowered to 18,” CIRCLE officials said.

Youth voting in 2022 is on track to match or exceed 2020, with 37% reporting they will “definitely” vote in the midterm elections, according to an April 2022 poll by the Institute of Politics at Harvard Kennedy School.

Young adults appear likely to vote in the midterms because they’re motivated by high-profile Supreme Court rulings, mass shootings and congressional hearings, NBC reported in June.

The history

Young voters have had the lowest turnout of all age groups in past U.S. elections and shouldn’t be viewed as a monolithic group, said CIRCLE’s Communications Team Leader Alberto Medina.

Half of young people don’t have a college degree, for example, so “what’s going to work to engage one young person and help them grow into a voter might be vastly different than what another young person needs—based on the community they come from, or their interests and experiences,” Medina said.

Young people are spread fairly evenly along the political spectrum, too. In a 2018 poll, CIRCLE found 56.4% chose to affiliate with a political party—33.1% are independents, 35.5% are Democrats and 20.9% are Republicans.

Politicians would pay more attention to the concerns of young people if more of them came to vote, said Tappan Vickery, HeadCount senior director of programming and strategy. Typically, youth voter turnout drops off by about 50% in midterm elections, compared with presidential elections, she said.

Aguilar noted that 8 million 18-19 year olds are now eligible to register to vote for the first time, but many feel disconnected from politics. They’re impatient with slow-moving changes in policy because they’ve grown up seeing things happen in real time in the digital world.

“Young voters want to see change,” Vickery said. “There are people who are not happy with the process because they don’t feel like change is happening enough. But they’ve been turning out, and hopefully they’ll turn out again because change is slow.”

Civic action

Young people tend to vote for change, and a desire to close the political generation gap tops their list of issues.

President Biden is 79 years old. Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, is 82 years old. Mitch McConnell, minority leader of the U.S. Senate, is 80 years old. And the list goes on.

The country’s political leadership represents a generation that will not have to live with the long-term effects of their decisions. But they’re shaping the lives of today’s young people.

That’s why investing in young people is the only way democracy will survive, said Maxim Thorne, CEO of the nonpartisan, nonprofit Civic Influencers, a group that works to engage young people in politics.

“From the birth of this nation to current times, young people have led the charge in activism and a belief in democracy,” Thorne said.

Organizations like Civic Influencers and HeadCount meet youth where they are—at colleges and universities, trade schools and even events such as concerts and music festivals.

“It’s a really powerful moment to think about the size of a room or space at a [music event] and the number of people you can connect with and talk to,” Vickery said. “Peer-to-peer voter registration is one of the most effective things you can do.”

Young people engage with politics differently than other age groups, Vickery noted. Social media is a great tool, but it’s impersonal. Meeting them in spaces where they already are makes them feel more comfortable to ask questions and interact.

Thorne agreed. “It’s wonderful when the speaker, the president or the majority leader speak, but young people don’t necessarily listen to these people,” he said.

Where youth votes matter

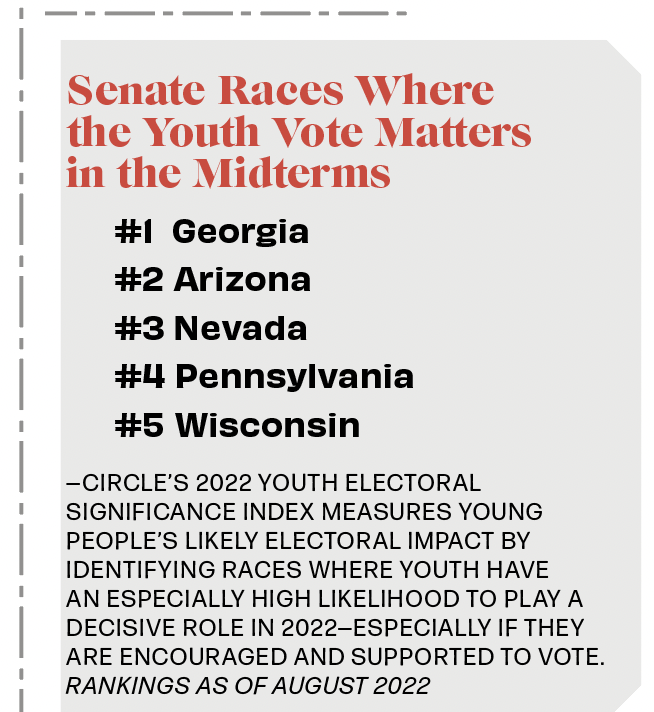

The youth vote could prove decisive in the midterms, research by CIRCLE indicates. The center uses a Youth Electoral Significance Index (YESI) to quantify young people’s likely impact.

“These are database rankings of the races where we believe young people could have a decisive impact on the result, and actually swing the election in many cases,” Medina said.

CIRCLE takes into account election laws, age demographics of a state or district and recent history of youth voter participation.

According to CIRCLE’s findings, the top five Senate races with youth electoral significance are in Georgia, Arizona, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. They can influence gubernatorial races in Wisconsin, Arizona, Kansas, Michigan and Georgia. They could hold the key to House races in districts that include Washington’s 8th, Kansas’s 3rd, Virginia’s 2nd, Colorado’s 8th and Michigan’s 3rd.

“Young people have power—they can decide elections,” Medina said. “Research consistently shows that young people are incredibly passionate about social issues. They care about what’s happening in their communities. They care about what’s happening to their peers.”

In 2020, for example, 12 congressional seats were flipped by 1%, which Thorne credits to campus involvement. The House race in Iowa’s 2nd Congressional District was won by just six votes.

Candidates across the country are winning races by fewer votes with each election cycle. But to have a voice in who wins those increasingly close elections, young voters—and voters in general—should understand the election laws in their states, Vickery said.

“Election laws changed in 2020 because of the pandemic, and 36 states have changed their laws again since 2020,” she noted. “So, I would not make the assumption that voting is exactly the same as it was the last time you turned out. Take the time to make a plan to vote and make sure you understand the process so that you don’t get hung up.”