The Case for Political Debates

Candidates should confront each other in structured debates—not the formats of recent years

The year is 1960. Presidential hopefuls John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon take to the stage for the first televised presidential debate in American history. As the vice president of the United States, Nixon is well known. Kennedy, a Democratic senator from Massachusetts, is out to prove he’s experienced enough for the job.

But the headlines that followed this historic exchange didn’t focus on the quality of the candidates’ remarks or the efficacy of their policy prescriptions. It was Nixon’s five-o-clock shadow and “gaunt appearance” that dominated the discourse.

Nixon had refused makeup; Kennedy opted for a “light powdering.” Many thought the young senator won the debate against the significantly older-looking and seemingly agitated Nixon. Later, in his memoir, Nixon wrote: “I recognized the basic mistake I had made. I had concentrated too much on substance and not enough on appearance.”

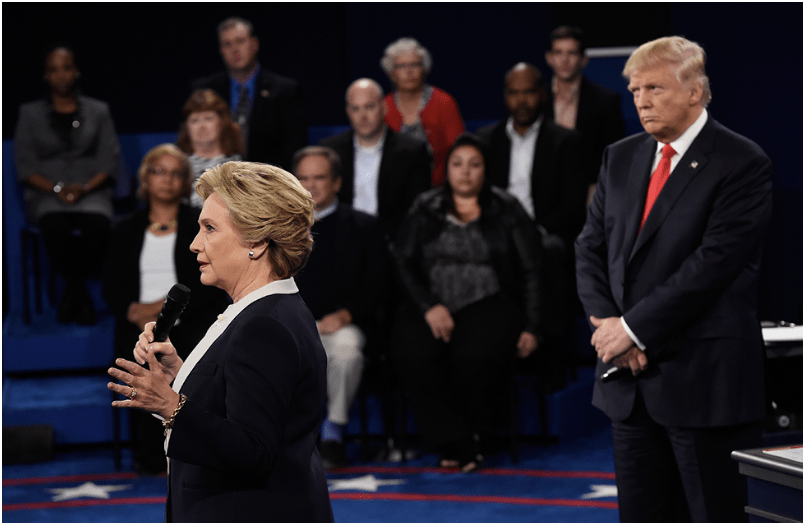

Many Americans would say the same thing about subsequent presidential debates. Today’s debates have been reduced to a string of “gotcha” questions for candidates. They result in personal attacks, repetitive questioning, uninformative soundbites and scripted rebuttals. There is no serious discussion of policy.

They are, by design, joint press conferences with journalists playing the role of jury instead of moderator. After the last round of debates, New York Times journalist Elizabeth Drew’s Op-Ed titled Let’s Scrap the Presidential Debates went viral on social media, sparking a vibrant debate about, well, debates.

The year is now 2022. The Republican National Committee (RNC) has taken a stand against the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD), voting unanimously to withdraw from the CPD entirely.

“The Commission on Presidential Debates is biased and has refused to enact simple and common-sense reforms to help ensure fair debates, including hosting debates before voting begins and selecting moderators who have never worked for candidates on the debate stage,” RNC Chair Ronna McDaniel said in a statement.

Presidential debates have always been political dog and pony shows, but if we want to restore truth and accountability to the public square, we need to fix the formats and elevate the role of the moderator beyond that of an interviewer.

The trouble here is that debates win elections. Millions of Americans watch the presidential debates, and for some undecided citizens, the debates play a pivotal role in influencing their vote.

Debates offer the only opportunity for voters to see candidates face-off directly. We get a sense of how they handle themselves in a disagreement. How ardently they defend their values and beliefs—and formulate convincing arguments—directly informs our perception of their leadership ability.

Personality, character and trustworthiness are key ingredients to leading successful negotiations with other titans on the world stage. For many Americans, their vote is won on the debate stage.

So, if presidential debates win elections, why are they always so bad?

The short answer is this: The debates we see today were born of legal strife and contentious partisan political rivalry, and things haven’t improved much. The long answer is complex and requires a dive into American broadcast history.

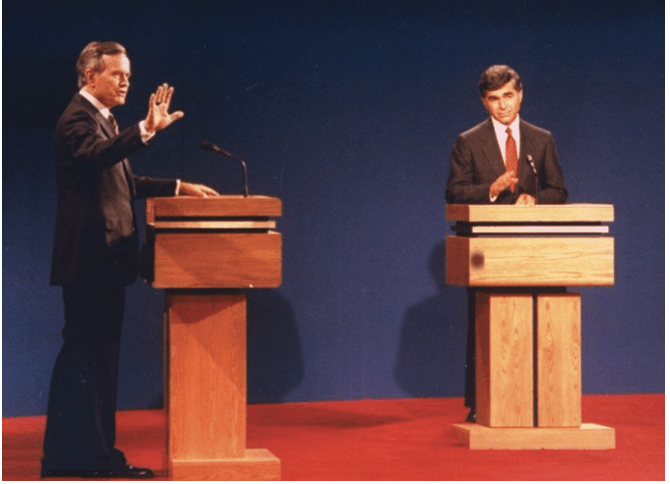

After the Kennedy-Nixon debates, an incumbent candidate with a lead in the polls wouldn’t agree to a debate for the next 16 years. Why would they risk the entire election on one gaffe, a single misstep or bad lighting? They were able to say no, so they did say no.

Then, in 1976, the tides turned. Incumbent President Gerald Ford agreed to debate Jimmy Carter, a newcomer from Georgia. When the debate organizers asked why President Ford would take the risk and break a 16-year hiatus, he responded: “I’m 32 points behind. What the hell else am I going to do?”

Carter wanted to debate because he didn’t think the country really knew him well enough to grant him a win at the ballot box. Even though he was ahead, he believed he needed the visibility.

One minor detail: It was illegal for broadcasters to stage a debate at the time.

Since the New Deal, broadcast networks had been barred from staging political debates. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) intended to guarantee fairness on the airwaves, but broadcasters believed the ban prevented them from presenting candidates and issues to the public.

Exemption from the “equal time law” required that an outside party sponsor the debate and that it be broadcast in its entirety and no later than a day after the debate occurred to ensure it was considered a “bona fide news event.”

Enter Newt Minow, the godfather of America’s presidential debates. The former chair of the FCC, Minow organized the Kennedy-Nixon debates and would later serve as the first co-chair of the Commission on Presidential Debates.

Minow worked with the League of Women Voters, a respected and long-standing, nonpartisan civic organization, to resurrect the debates in

1976 and 1980. But many would argue the presidential matchups weren’t held in the best possible way, largely because of candidates’ demands and conditions.

For starters, they negotiated a debate format that—by any standards—wasn’t even a debate. The League wanted the candidates to debate each other (which seems reasonable given the circumstances), but the candidates refused.

“They were totally averse to the idea of confronting one another in rebuttals or conversation,” recalls Minow. They agreed to take questions from journalists and moderators but not from each other. A panel would ask questions, and the candidates would avoid any sense of confrontation. No reaction shots of the live audience would be shown, a practice which persists to this day.

After hosting two presidential debates, the League dropped out entirely. According to Minow, the group felt the parties were colluding on the terms and dictating how the debates would need to happen. The League stated it had “no intention of becoming an accessory to the hoodwinking of the American public.”

The only way debates could occur, it seemed, was to have the two major parties institutionalize the idea of presidential debates. The FCC began to allow broadcasters to hold political debates, and what evolved is the current Commission on Presidential Debates.

But the role of the CPD isn’t just to mount debates. It also negotiates with the parties so that debates can happen every election cycle. That’s not easy, but the debates have happened for the last 30 years.

Many notable, make-or-break moments have marked debate history. But most post-debate analysis misses the point: It’s not about winning or losing—it’s about informing the electorate.

Now, the debates have become part of an existential problem as Americans struggle to understand what is a fact and what isn’t. It’s hard to believe, but that’s where we are.

if his wife were raped and murdered—haunted him during the rest of

the campaign.

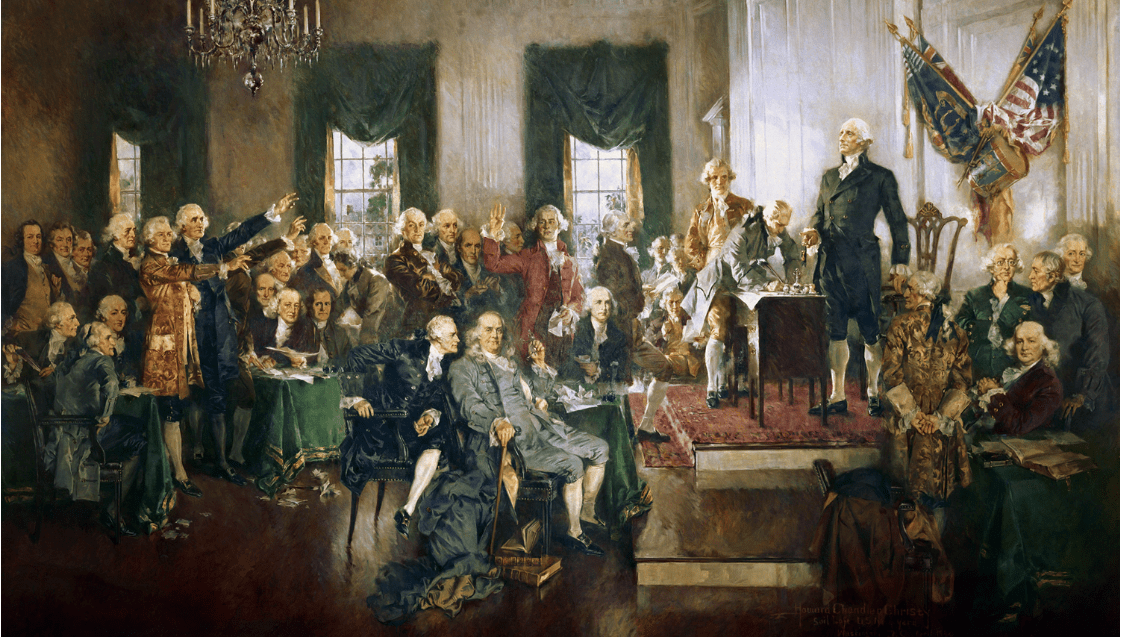

It’s the role of debate to bring both sides together to examine the arguments with reasoned analysis and use evidence to support arguments that drive sound policymaking. Debate is critical to a functioning democracy. That shouldn’t come as a surprise because the first democracies were established through rigorous, intelligent and structured debates.

So, what does all of this mean for 2024? The RNC’s decision to leave the CPD signals a shift toward a better definition of the role of debate in American elections.

“We are going to find newer, better debate platforms to ensure that future nominees are not forced to go through the biased CPD in order to make their case to the American people,” McDaniel announced. “I’m hopeful we can establish a more meaningful and constructive approach to debate for both parties, starting with the format and choice of moderators.”

The stakes are high. Seeing our elected officials engage in substantive debates would serve as a model for how we the people should navigate tough conversations about increasingly complex questions.

Fake news can’t survive the scrutiny of real debate. But, can civil society survive without a vastly improved presidential debate stage? It’s time to clean up America’s five-o’clock shadow of civil discourse and establish a new playbook for the presidential debates, driven by civility, substance and quality.

Clea Conner, CEO of Intelligence Squared U.S., a nonpartisan debate organization, is advocating for a

new take on the debates in 2024.