On the Road Again: A Comeback Case Study

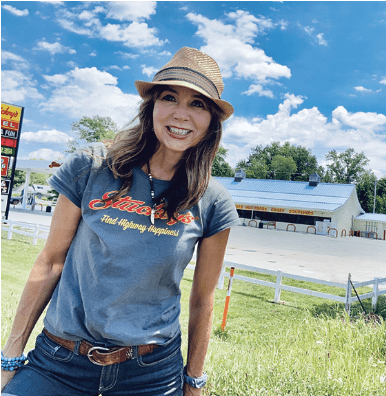

The granddaughter of the founder of Stuckey’s, the roadside oasis stocked with pecans, candy and souvenirs, is reinventing the nostalgic brand in what she calls an 85-year-old startup

Stephanie Stuckey awakens to an LL Cool J song she can relate to: “Don’t call it a comeback, I’ve been here for years.”

Customers of her family’s roadside stores often feel a twinge of nostalgia when they load up on pecan rolls, divinity confections and souvenirs. They remember enjoying the same treats years ago on family vacations. She calls the Stuckey’s brand an 85-year-old startup, and she’s in charge of hitting the reset button. She’s rebuilding the Stuckey’s story one pecan at a time online and in retail stores.

THE BACKSTORY

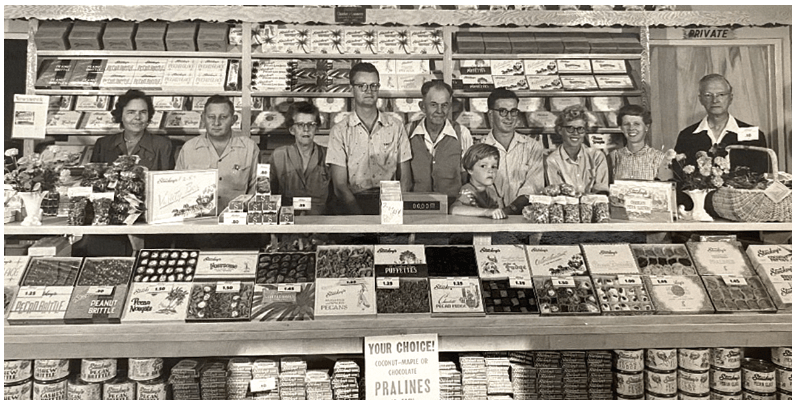

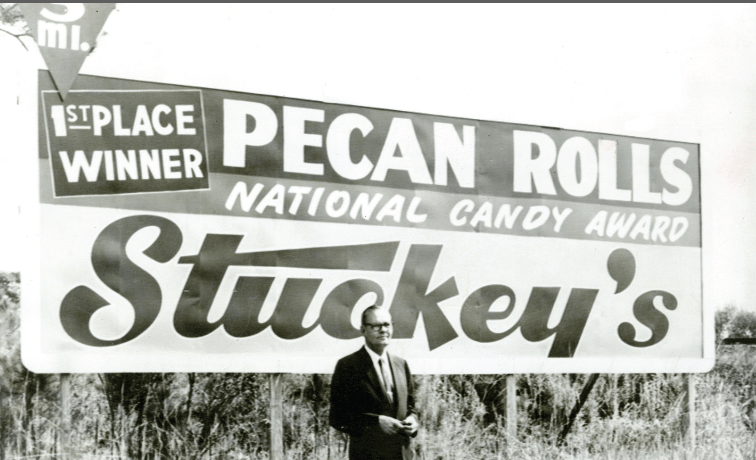

It all started in 1937 when W.S. Stuckey Sr., Stephanie’s grandfather, set up a roadside pecan stand in Eastman, Georgia. It was during the Great Depression, and he needed a job. Pecans sold well, and when his wife, Ethel, added her pecan log rolls and pralines to the mix, the couple soon had enough money to open their first store.

In the next 25 years, Stuckey’s grew to more than 368 stores along the interstate in 40 states “offering kitschy souvenirs, clean restrooms, gas, pecan treats, and the iconic pecan log roll, becoming the country’s first roadside retail chain.” The signature white farmhouse, sometimes with a teal or blue roof, found fans young and old, particularly during its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s when President Dwight D. Eisenhower was creating the U.S. Interstate Highway System.

W.S. “Bill” Stuckey Jr. remembers that time well.

“When the interstate came along, we thought that was the end of business—it split the road,” said the 87-year-old father of Stephanie Stuckey. “Truthfully, it’s the best thing that ever happened to us. That’s when Stuckey’s really took off.”

Stuckey Jr., who was serving as Stuckey’s executive vice president at the time, seized the opportunity.

“My father never wanted to expand west of the Mississippi because of transportation since everything was made in Eastman,” Stuckey remembers. “I got the bright idea to put together a company and add a 15% freight charge on all products. Every store west of the Mississippi was brand new with new designs.”

There was only one way to direct drivers to the new stores.

“Billboards built Stuckey’s,” he said, and drove traffic from that new interstate right to the Texaco gas pumps at every Stuckey’s stop.

A savvy businessman, Stuckey Sr. negotiated a lucrative contract with Texaco, an American oil brand owned and operated by the Chevron Corp. The company distributed gasoline credit cards to many families who used them regularly on road trips. Every time they stopped at a Stuckey’s to fill up, Stuckey would collect a Texaco rebate which eventually reached 3 cents on every gallon of gas sold, he said.

Stuckey’s continued to grow until W.S. Stuckey Sr.’s health declined and he pursued a merger with the Pet Dairy Corp. in 1964. Later, the company was owned by IC Industries, a Chicago-based railroad company, until Bill Stuckey Jr. bought it back in 1984. He and his partners ran the company for another 30 years until he retired. A skeleton staff remained in place to manage operations for the next seven years.

His daughter, Stephanie, bought the company on Nov. 1, 2019, after spending 14 years in the Georgia General Assembly House of Representatives.

FAMILY BUSINESS

“I know I would not have taken this on if it was not my name out there,” Stephanie said. “I have such great memories of my grandfather and I knew how much pride he took in what he’d done.”

Her grandfather remained involved in the company for about a decade after he sold it and often took his granddaughter by the hand when he visited the candy plant where she saw the molten candy being poured onto the marble tables and cracking. She would grab it and gobble it up, much to her grandfather’s delight.

“He just took such pleasure seeing what he built and having us appreciate that,” Stephanie said. “And then after he died, I saw what happened to his vision, and it was heartbreaking. I never thought we’d get a chance to rebuild it.”

Although her father did get the company back, it was not his priority, she said, because he also was running five other businesses which propped up the failing family business.

After her dad retired, the company staggered on.

“They started losing money to the point that they were six figures in debt,” Stephanie said. “I didn’t want our story to end that way.

“I didn’t want to have a legacy of regret where my grandchildren would ask, ‘Why didn’t you save the family business when you had the chance?’”

ANATOMY OF A COMEBACK

“I’ve got the last name Stuckey. I know the story because it’s my story and the brand is so much a part of me that I think I can tell it in a way that’s authentic,” said Stephanie, who was named after her grandmother.

She jokes that she’s the chief executive officer, the chief brand officer, the chief storyteller and the chief sales officer because she believes branding is sales. She said it’s similar to the old adage if you build it, they will come, but if you brand it, they will also come.

“We’re an 85-year-old startup,” Stephanie said. “We’re back to where we were very much in the beginning, as far as trying to rebuild the company. Fortunately, we are no longer six figures in debt. But there’s a lot of market share that we need to reclaim to move us forward.”

She has a multi-tiered strategy to bring the Stuckey’s brand back. The company is starting with what is generating the most profit: consumer products. The company makes in-shell and raw shelled pecans to toasted and flavored snack nuts, as well as a full line of candies and merchandise that account for 80% of the company’s $12 million in revenue. Pecans, she said, are the company’s strongest opportunity, particularly since Stuckey’s is based in Georgia, the No. 1 state for producing pecans.

“We’re uniquely situated to be the brand associated with pecans, and as the trends are going toward more healthy diets, we think there’s a real market opportunity right now to come in and promote pecans and build on the fact that we do have some market value,” she said.

One of Stephanie’s first initiatives was to partner with RG Lamar Jr., a longtime Georgia pecan farmer, family friend and owner of a healthy snack brand called Front Porch Pecans. He’s now co-owner and president of Stuckey’s and works side-by-side with Stephanie, who first identifies channels of product distribution, and he closes the deals with grocery stores and such national chains as TravelCenters of America, Casey’s, Ace Hardware, Bealls and more.

Next, the team revamped the company’s website, increasing product sales from $25,655 in 2019 to $229,250 in 2021—an increase of almost 800%.

Recognizing the need to increase product production in-house, the partners acquired a pecan shelling plant, a candy plant and a fundraising business based in Wrens, Georgia.

Last year, they saw a profit in excess of $2 million—the best bottom line since she took the business over.

She looks to other companies, like Moon Pie, Krispy Kreme and Little Debbie, for strategic inspiration. They’re American-made brands that have stayed in the family and are still produced stateside. Little Debbie is the granddaughter of the founder and sits on the board of the company. All of those brands, she said, have an emotional connection with their consumers.

That nostalgic connection is what Stuckey is reminded of when she visits the 65 licensed Stuckey’s locations, primarily in the southeastern states. Stephanie, also known as “Roadie,” promotes these road trips to her more than 88,000 followers on LinkedIn, where her people are.

“I draw on my background in politics. I was in elected office for 14 years, and you go to your base first,” Stephanie said. “Our base are people who remember our brand—age 45 years and up with the sweet spot being 55 to 65 years old. They have money, they’re still active, they’re still road-tripping, they’re buying gifts for their family, they’re still in business, they’re loyal and they enjoy the nostalgia of our brand.”

She’s making sure this core set of customers and fans know Stuckey’s is back. As the company focuses more marketing on healthy trends and distributing nut products in convenience stores, she anticipates attracting millennials and then zoomers, too.

“We want to be not just on the candy aisle,” she said. “We want to be on the nut aisle, too. That’s where we’re going to pick up more new customers. I am also finding people in their 30s who are connecting with our brand because their parents liked us.”

Once she gains brand value, the company will be in a better position to open stores.

“But it won’t be my grandfather’s stores. It won’t be 368 stores in 40 states,” she said. “I literally mean maybe 10 that we would own and operate that would be very brand forward and almost like incubators for testing product and ideas and really a space where we can elevate the brand.”

She anticipates these Stuckey’s stores will someday be roadside oases in such tourist destinations as Branson, Missouri, or Pigeon Forge, Tennessee.

PECAN PRO

RG Lamar Jr. was handed the reins of his family’s 2,300-acre pecan farm in Hawkinsville, Georgia, 14 years ago. With 30,000 pecan trees and an annual production of about 2 million pounds of pecans, Lamar Pecan Co. is among the largest pecan farms in Georgia and is working with Stuckey’s. Now that he’s focused full-time on Stuckey’s, his stepbrothers are running the farm, planting and maintaining pecan trees that take anywhere from seven to 15 years to reach full production.

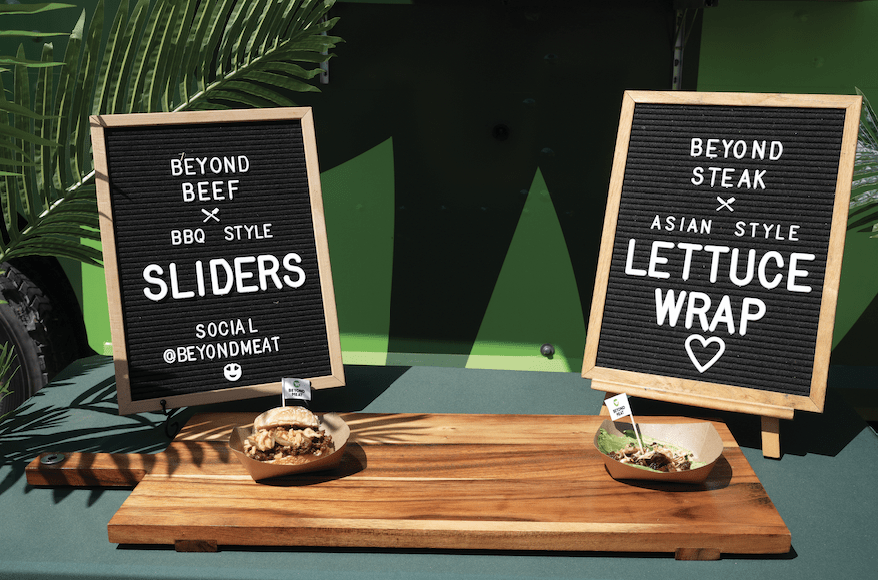

Lamar has a love for the taste of pecans he describes as “sweet, buttery, nutty.”

“Anyone who is involved with pecans loves to snack on them, but really nobody else in the world thinks of them that way,” Lamar said. “I’ve always had a desire to find a way to change that, and one of the great opportunities we have with Stuckey’s is it is the single most recognizable brand name in the world that is associated with pecans. So, that’s really the heart of the opportunity and why Stephanie and I decided to partner.”

The partnership also makes sense because of what happens when someone shells a pecan. Lamar said there are about five sizes of halves—often used in pies—and about five sizes of pecan pieces.

“Any pecan sheller will tell you, the trick is selling the pieces,” he said. “Any idiot can sell pecan halves. That’s easy. What’s hard is selling the pieces, and that’s what will make or break your business.”

But many of the candy products Stuckey’s sells use only pecan pieces, which makes the partnership a really good fit.

The team has expanded the brand and products—which are over 600 SKUs—into three main store channels: convenience, grocery and what Lamar calls alternate stores, which include Bass Pro Shops, Tractor Supply, Bed Bath and Beyond, and Cracker Barrel. Stuckey’s B2B sells to 2,000 gift stores, tourist destinations, hotel gift shops, state parks, gourmet food markets, candy stores, gift basket companies and other smaller retailers.

They’re discovering pecans are a bit of an untapped market. Lamar blames it on the other tree nuts, which have been marketed for nearly a century, leaving the pecan behind in the dirt. The almond was promoted as extremely healthy and made a great snack, and soon, he said, the almond industry took off.

“So, what has happened is the nut industries have spent money on marketing and have persuaded the public to choose their nut as a snack, oftentimes on the basis of health,” Lamar said. “They’ve also provided it in a convenient package, and pecans have not done that. We’ve been content to let folks eat pecans in pie one time a year, and that was an egregious mistake that our forebears made.”

But now the pecan industry does have the marketing dollars and the research, he said, showing that pecans are at least as healthy as these other nuts that consumers often munch on now.

“Many people don’t know that pecans have the most antioxidants of any nut, and almost nobody knows that pecans are the only nut native to this continent,” Lamar said, adding Stuckey’s is producing resealable, 4-ounce snack packs for $5.99. “I am 100% persuaded that over the next five to 10 years, people will begin to eat pecans as a snack in the way they do other nuts.”

Lamar said the company has reached production capacity with the 50 products it makes in-house, and it’s hoping to get the financing for a large building expansion and the equipment necessary to automate key products. He projects that will enable the company to produce 20 times as much product.

Production of the pecan log rolls, he said, is about five logs per minute because they’re still making them by hand, just as Ethel Stuckey did back in the day. With increased production, he expects to make about 100 logs per minute.

Rewriting the story

Bill Stuckey Jr. says the family name is one of the most recognized brands out there—for a certain generation—and the potential for sales on the internet is strong.

“What started Stuckey’s was pecans,” Bill Stuckey Jr. said. “I still think that’s the demand, if nothing else, health-wise, of all the nuts, the pecan is the quality nut.”

Pecan expertise is what he says RG brings to the table. He knows the business, and he’s confident they make the perfect team: candy, pecans and salesmanship.

“Stephanie is an overachiever,” her dad said. “Stephanie has got the ability, but the main thing is, she’s got the enthusiasm. She can sell. She’s smart.”

Stephanie Stuckey is rewriting the Stuckey story.

“I want it to end with us being a $100 million in sales company that is associated with pecans,” Stephanie Stuckey said. “I want us to be the go-to nut on the snack aisle. But we’re still known as a road trip brand, and that’s still at the core of what we do. Selling pecan snacks is a way that we’re able to grow the brand. But I still want us to celebrate the joy of exploring small town America by car.”

She wants customers to have an emotional connection with Stuckey’s products, just like she does.

“They’re not just buying up a pecan log roll. If they’re buying the story of our brand, they’re buying the story of my family’s history, they’re buying the fact that my grandfather started during the Great Depression with a stand on the side of the road with no money. That’s so much more meaningful than some generic candy bar.”

Social Savvy

Stephanie Stuckey wants to be authentic.

Her name is on her product and so is her family legacy. Her social media posts are honest and enduring. Even after a career as an attorney and more than a decade as a state legislator, she looks almost 18 with her long, chestnut-brown hair and curtain bangs, wearing T-shirts, cut-off jean shorts and a toothy grin. Stuckey says it’s all in the lighting, but the truth is she is the fresh, young face behind an 85-year-old brand.

LinkedIn is her choice of social media, where she has more than 88,000 followers. That’s where her people are, she says. Her customers range from 45 to 65 years old. They’re active, savvy and in business.

“We’re looking to the business profession,” Stuckey said. “The way we’re growing the brand is B2B sales, but B2C as a component of it. The bulk of our profit is getting into retail chains and retail stores. So, the more we connect with the CEOs of grocery stores, convenience stores, department stores, any retail chain that sells gifts, we’re a good fit. So, that’s LinkedIn. That’s where you find that audience.”

But it’s also what’s in her posts that matters to Stuckey.

“I think how I’ve been successful is not posting the typical post. I tell the story of the entrepreneurial journey in a very real way. I put it all out there,” Stuckey said, hoping she doesn’t share too much information. “I try to be very upfront about what’s happening with our brand.”

In one post Stuckey admits: “I had no experience running a company, much less a lemonade stand. What made me think I could turn Stuckey’s around when it was six figures in debt with no business plan or marketing budget?”

Stuckey doesn’t post ribbon-cutting or award ceremonies on LinkedIn. Instead, “Roadie”—a nickname she earned by making frequent road trips—likes to be pictured in her blue jeans and T-shirt stocking boxes during the annual inventory count or posed outside one of the 65 Stuckey’s locations. She takes a lot of pictures during her trips and makes sure she posts multiple times a week every week. Her posts tell the real story of her efforts at rebuilding her brand.

“That’s different and people appreciate that,” Stuckey said. “People can relate to that a lot more than they can some of the more businesslike type content.”

That authenticity is the connection Stuckey relies on to move her brand and business forward. But she also knows about 15,000 of her 50- and 60-something-year-old customers also have another social media fav.

Yes, she’s also on Facebook.