Grain: The Next GameStop?

Even corn and soybeans are not immune to the perils of social media. According to online chatter, grain prices in 2022 will hit $18 to $19 per bushel of corn, $30 for soybeans and $42 to $45 for wheat. While those price forecasts may seem far-fetched, anything is possible and the 2020 price action on crude oil is proof of that.

The odds of $18 corn are about the same as the odds that the world will ever see crude oil trade to -$40. Wait a minute. That did happen back in April. So, anything can happen in this environment. But is it likely? Probably not.

Old crop—new crop

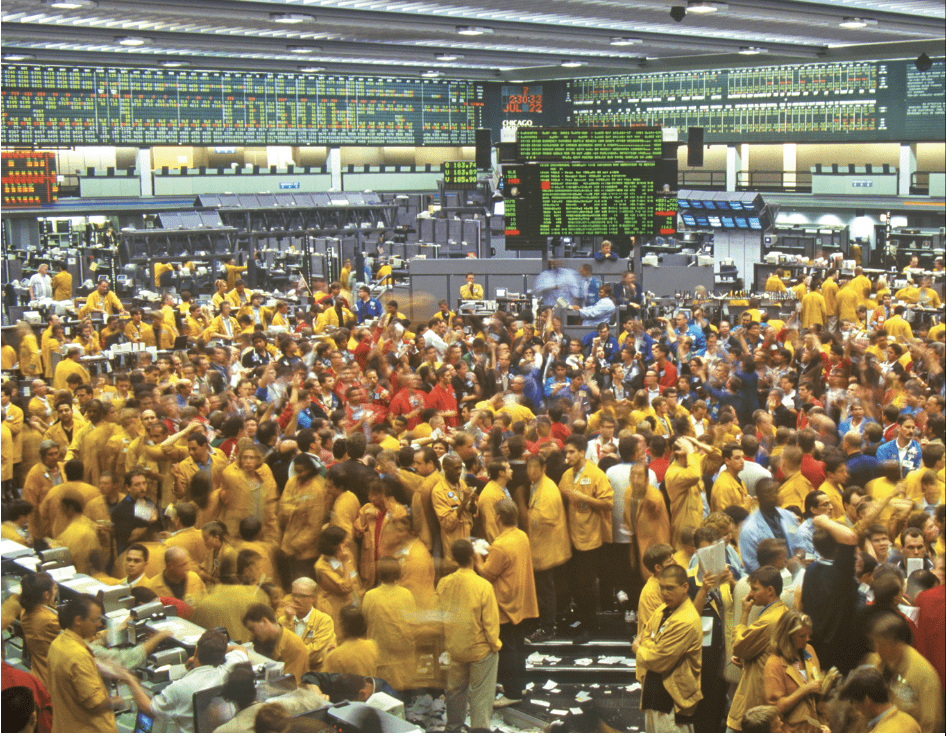

Spread trading in the grains seems to be gaining popularity these days and for good reason. With high volatility in grain markets, spread trading may be one way to take on less risk and lower margin requirements.

However, when spread trading grains it’s important to understand the difference between crop years and their relationships to each other. While new crop and old crop contracts certainly are related, they do have different factors influencing prices—and sometimes very different fundamentals. So, what does the relationship between the new crop and old crop mean?

In grains, traders refer to last year’s crop as old crop. This is the grain supply that farmers grew last year and the nation is currently using. New crop is the grain that will be harvested in the fall. The marketing season for corn and soybeans begins when crops are harvested, starting in September, and ends when the new crop harvest begins. There’s a lot of overlap in fundamentals between any grain’s old crop and new crop.

The biggest unknown factor for the next year is supply. Grain production can vary—sometimes dramatically—from one year to the next depending on how many acres are planted and how good or bad the weather is during the growing season.

Under normal market conditions, new crop contracts usually are at a premium because no one knows how the next growing season will go. This production uncertainty keeps new crop prices higher.

That can be exaggerated in a bear market, as old crop prices can go lower to try to spur demand while at the same time keeping a premium in new crop because farmers still have to grow it.

In a bull market, the relationship can flip. A bull market generally means that demand is strong relative to supply. In that scenario, many times old crop prices will be higher than new crop prices. The idea is that the balance sheet is tight now but could be better next year if production is good. When old crop prices are higher than new crop prices, this is generally a good indication of a bull market. Because of this relationship, old crop and new crop prices do tend to go in the same direction, but that direction is usually led by old crop.

So, in a bull market the old crop usually moves higher, faster and farther than the new crop, and in bear markets old crop usually moves lower, faster and farther than the new crop.

This year?

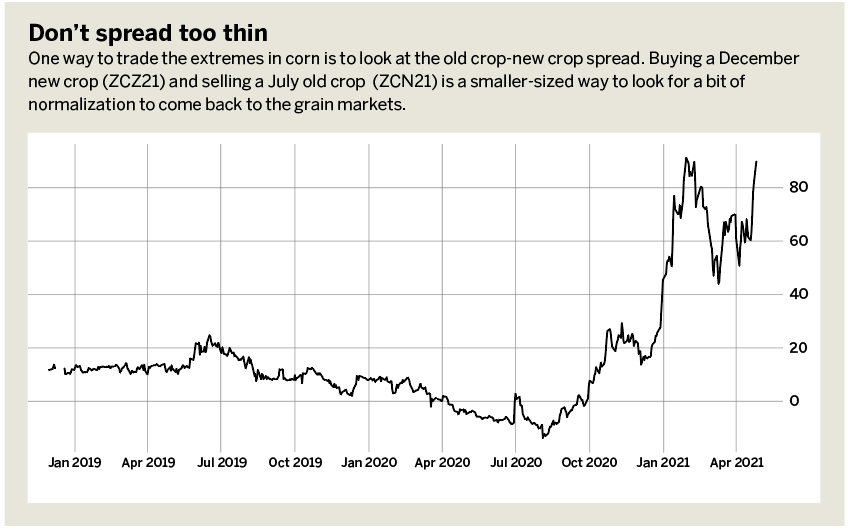

As of April 26, there was a 90¢ premium to the July (old crop) over the December (new crop) corn futures contract. This is a large premium to the old crop contract, even during a bull market. This is a rather interesting relationship, considering that corn has now rallied over $3 off its lows of April last year. Back in April 2020, when corn was at its lows, the new crop December contract held a 14¢ premium over July. This was a good indication of a bear market at that time.

With July now holding a 90¢ premium over December, it means that the July contract has rallied 76¢ more than the December contract during this rally off of lows. This is what traders would expect from a bull market, and this spread can indicate possible exhaustion on this upside move. It’s the biggest difference between old crop and new crop since 2013.

One interesting way to play the “extremes” in corn is to look at the old crop-new crop spread. Buying a ZCZ21 (December new crop) and selling a ZCN21 (July old crop) is a smaller-sized way to look for a bit of normalization to come back into the grain markets.

With the tight old-crop stock situation, the markets will be highly attuned to even small weather problems and arguably are already building in some risk premium because of dry conditions in the United States. This will likely spur some gut-wrenching volatility later this summer as the market reacts to every change in the weather forecast.

Remember, volatility doesn’t mean that prices just go up. It can also mean the opposite. Eventually, traders will want to take profits, and if that’s combined with ideal growing conditions or some outside market or geopolitical event, the market could see large moves lower.

Pete Mulmat, tastytrade chief futures strategist, serves as host for Splash Into Futures on the tastytrade network. @traderpetem