Big Crypto’s Campaign Cash

Two companies have opened up their crypto wallets to lead the corporate sector in 2024 election campaign contributions

Cryptocurrency companies account for nearly half of the corporate money contributed to the 2024 election campaigns—dwarfing spending by big oil, healthcare or any other sector, according to a report from Public Citizen, a nonprofit progressive advocacy group and think tank.

Of the $119 million the crypto industry has poured into the election, 80% has come from just two companies. One of them, Coinbase Global (COIN), is a publicly traded exchange offering more than 260 cryptocurrencies. The other, Ripple, is a privately held gross settlement system, remittance network and currency exchange using a cryptocurrency known as XRP.

Coinbase has kicked in $54.3 million this election cycle, placing it sixth on a list of the biggest organization donors compiled by OpenSecrets, a nonprofit that tracks campaign finance and lobbying and has roots going back to 1983. Ripple’s $52.5 million in contributions puts it seventh on the list, right behind Coinbase.

Although spending by those two companies leads the corporate sector, their generosity is eclipsed by contributions from individuals. Timothy Mellon, grandson of Andrew Mellon and heir to the Mellon banking fortune, has chipped in $165 million this cycle, some it to former President Trump and some to Robert Kennedy Jr. Mellon’s contributions rank first on the OpenSecrets roster.

Privately held companies have also committed large sums to the election, like the $79.7 million from Susquehanna International Group, a trading and technology firm. Ken Griffen and his hedge fund, Citadel, are in for $75.4 million. They place second and third on that list.

But the cryptocurrency contributions don’t pale in comparison to the donations from those largest contributors.

Crypto goes hyper

Rick Claypool, research director at Public Citizen and author its report, put it this way: “Corporations can’t vote. But the sole reason crypto is a hot-button topic in this election cycle is that crypto businesses are spending eye-popping sums to make themselves impossible to ignore.”

Unsurprisingly, most of the crypto cash has gone to public action committees (PACs) working to elect candidates who support the industry. Crypto has faced intense scrutiny during the Biden administration.

Meanwhile, former president and Republican nominee Donald Trump, once a crypto critic who called it a “scam,” has reversed his position and looks upon it favorably, says Anthony Scaramucci, founder of SkyBridge Capital and former White House communications director.

That’s perhaps an understatement. Trump and his sons are launching a cryptocurrency venture called World Liberty Financial that the former president says will help turn the United States into “the crypto capital of the world.”

Moreover, Trump has attempted to exploit the rift between the crypto industry and the Democrats by pitching himself as the pro-crypto choice for the White House and delivering a keynote speech at a recent bitcoin conference, says CNBC.

Just the same, crypto industry money is flowing into both parties, as the House, Senate and presidency could all go either way in this tightly contested election.

And the same goes for many of the contributions from other corporate entities. But funding candidates can have drawbacks, too, as some companies are finding out the hard way.

Cancel my account!

When Netflix reports third-quarter earnings a week from today, we should get a clearer view of how co-founder Reed Hastings’ $7 million contribution to the Harris presidential campaign has affected the business.

But we already know his bequest prompted MAGA Republicans to launch a crusade on X to convince customers to cancel their Netflix streaming subscriptions. That resulted in an account closure average of 2.8% in July, an even steeper rate of defection than in July 2023 when the company stopped offering its most basic, least expensive subscription service.

It’s an episode that could give pause to management and board members at publicly traded companies who find themselves tempted to reach into corporate treasuries and make political contributions.

Besides, doing so would violate the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), which President Richard Nixon signed into law in 1971 to prevent companies from contributing directly to candidates for nationwide office or to national political parties. Still, there are plenty of legal ways to circumvent restrictive campaign finance laws, not to mention that the law has lost its teeth.

Sidestepping prohibitions

The FECA legislation doesn’t stop companies from funding candidates, parties and committees at the state and local levels. Twenty-nine states and countless municipalities have deemed that acceptable.

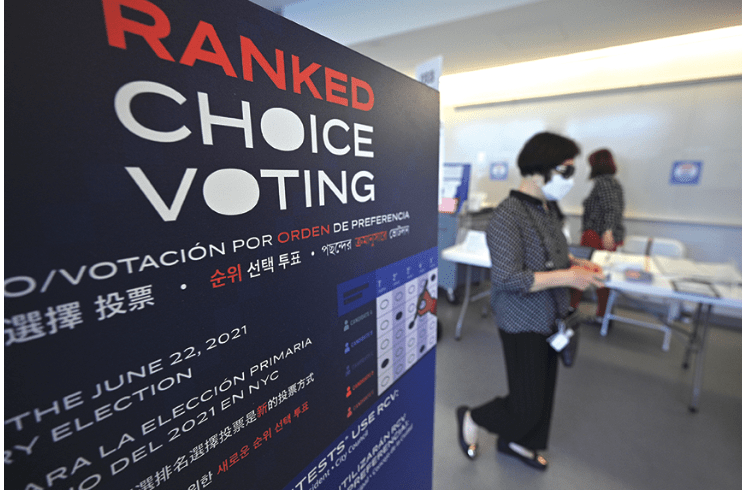

Also, nobody has told corporations they can’t fund national politics indirectly. They can do it through political action committees (PACs), trade associations, 501(c)(4) organizations, ballot measures and something called “direct independent expenditures.”

Some definitions may be in order, and we can begin with independent expenditures. In 2010, the Supreme court ruled 5-4 in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that the First Amendment prohibits restricting independent expenditures for political campaigns by corporations, nonprofit organizations, labor unions and other associations.

The Code of Federal Regulations defines independent expenditures as contributions for communications that advocate for the election or defeat of a candidate—so long as the money is spent without the request, suggestion, cooperation, consultation or in concert with a candidate, a candidate’s authorized committee or a political party.

Carrying on with our definitions, let’s go next to 501(c)(4) organizations, which the Federal Revenue Code characterizes as social welfare organizations. They’re allowed to participate in politics as long as they spend less than 50% of their revenue that way.

Another kind of group, political action committees, or PACs as they’re so often called, can provide cover for companies determined to spend on politics. They’re also known as 527 groups because of their tax-exempt status under Section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code.

It’s illegal for corporations or labor unions to contribute directly to PACs, but they can organize and sponsor a PAC and also provide financial support for the PAC’s administration and fundraising.

The Walmart Inc. PAC, for example, provided $975,000 to federal candidates in 2021-2022. Of that total, $495,500, or 46%, went to Democrats and $525,500, or 54%, went to Republicans.

That may seem paltry for Walmart (WMT), the world’s biggest company by revenue, but it’s only one of many ways the company makes it presence known in American politics.

Walmart affiliates and their 2024 contributions this election cycle include Sam’s Club $65,000, VUDU $46, Walmart Labs $9500, Walmart Pharmacy $3,500, Walmart Vision Centers $300, Walmart Transportation $3,000, and Walmart.com $1,000, according to OpenSecrets.

And that’s not to mention 2023-2024 contributions by two of Sam Walton’s offspring— $16 million by Rob Walton and $10 million by Alice Walton. Plus, Sam Walton’s daughter-in-law Lynne Walton contributed $12 million.

That’s interesting but what do we know about contributions by other publicly traded companies?

Public companies’ donations

Blackstone (BX) occupies the No. 17 spot on the OpenSecrets list of the biggest organization donors with 2023-2024 contributions of $24 million. But they’re among few publicly traded companies ranking high on a roster dominated by PACs, hedge funds, privately held manufacturing companies, trade associations and trade unions.

The plain fact is most of the companies in the S&P 500 stay tight-lipped about political contributions, as evidenced by Center for Political Accountability research. Just the same, the center has tracked down how much cash those companies have kicked into politics, broken down by categories.

In the 2020 elections, S&P 500 companies funneled $214 million through trade associations, $60.4 million through PACs and $30.7 million through 501(c)(4) organizations. They managed to contribute $32 million to candidates, parties and committees, while spending $16 million in support of ballot measures, according to the center’s website.

To a great extent, the companies managed to spend that much without disclosing their involvement in politics to the public, as documented by the center’s research.

Most companies in the S&P 500 have no publicly announced policy or simply made no disclosers in 2020—let’s consider that one bucket. The number of companies in that category ranged from 276 that don’t disclose contributions to candidates, parties and committees to 347 that decline to tell how much they channel through 501(c)(4) organizations.

A second bucket would hold companies that share some information about their largesse. That ranges from 81 that reveal some details of their involvement with PACs to 178 that make public some information about their contributions through trade associations.

The third bucket would be for companies with policies restricting or prohibiting certain contributions. They range from 29 that restrict contributing through trade associations to 120 that prohibit disclosures about independent expenditures.

Buckets aside, the ways companies choose to divvy up their contributions can aggravate the polarization cleaving the nation into two opposing camps.

Take what’s happening in formerly liberal Silicon Valley.

The big split

On the left, Reid Hoffman, billionaire co-founder of LinkedIn, has donated millions to elect Harris and persuade her to drop Lina Khan as chair of the Federal Trade Commission.

On the right, Elon Musk, who runs SpaceX, Tesla and X, is funding Trump, appearing with the former president at rallies and talking about leading a commission to reduce the scope of the federal government.

It’s reasonable to think Hoffman and Musk help lead the two factions forming in the Tech world.

But regardless of how they address the great partisan divide, public companies have found plenty of ways to contribute to the candidates of their choice.

Certainly some seek lower taxes and fewer restrictions by investing in conservative candidates, while others put their money behind candidates who promise to back progressive social causes. But a surprising number of corporate donors split their contributions almost equally between Democrats and Republicans. That way, the board room will have influence no matter who wins the election.

We’ll see how their candidates fare when Americans go to the polls less than a month from now.

Ed McKinley is Luckbox editor-in-chief.