$4.4 Billion Has Been Spent on This Election

Everybody follows presidential fundraising, but who knows where all that cash goes?

Whether it’s a billionaire subsidizing a Super PAC or a day laborer chipping in five bucks in response to an email, presidential campaign fundraising attracts plenty of scrutiny. But not as many of us are paying attention to where all the cash winds up.

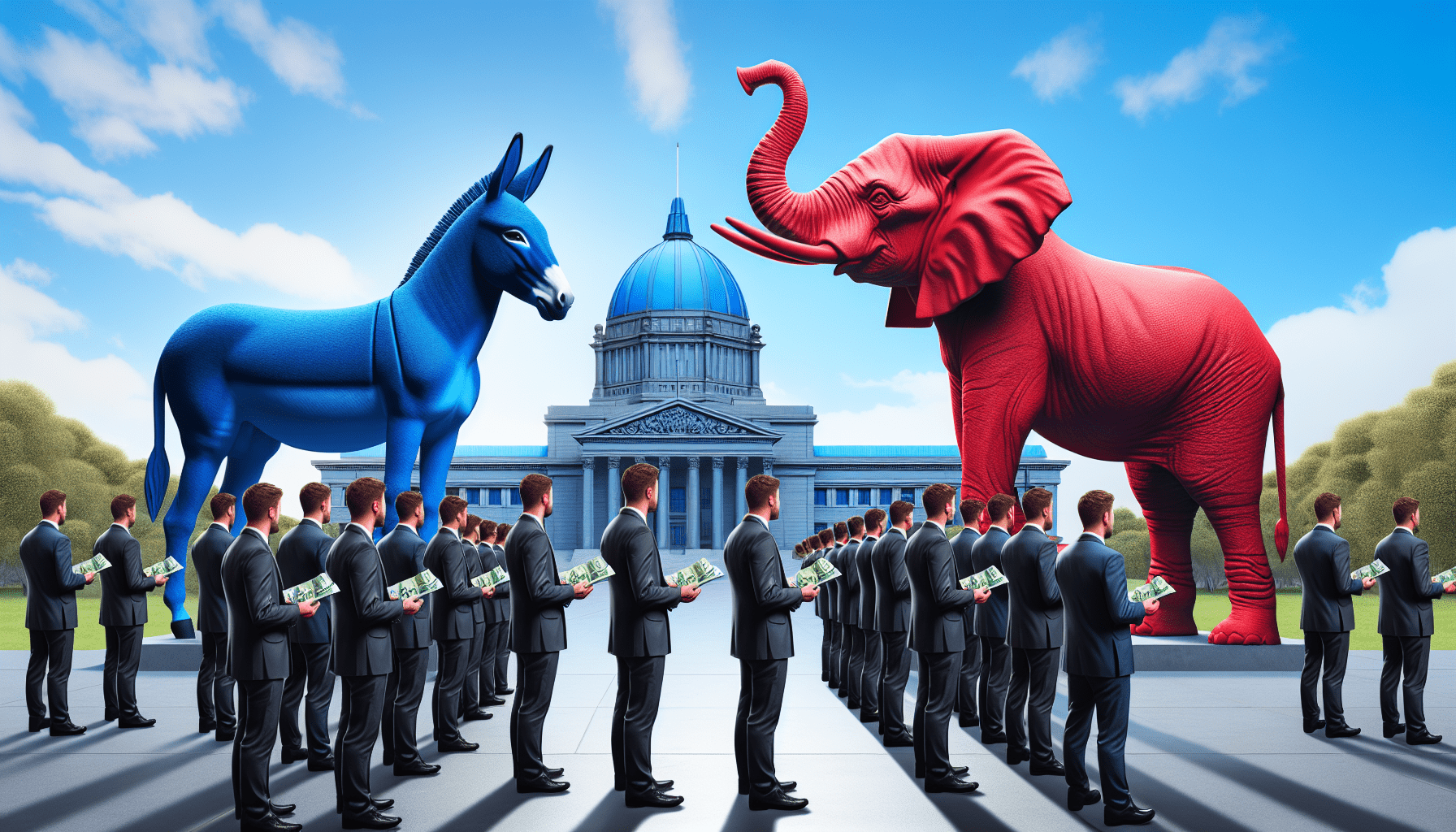

Perhaps we should. By the beginning of October, the campaigns of Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump had spent a combined $2.5 billion, according to data compiled by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and interpreted by the nonprofit OpenSecrets.

Of that total, the Harris campaign and pro-Harris outside groups had shelled out $1.6 billion, while Trump and pro-Trump groups had spent $1.0 billion. Besides those totals, Super PACs that spend on elections but aren’t allowed to work directly with campaigns burned through another $1.8 billion.

Where it all went isn’t easy to pin down, says Brendan Glavin, an OpenSecrets researcher. “Expenditure data can be very hard to parse. Vendors can receive large sums to perform varying tasks, which are broadly described in reports.”

Tracking campaign outlays

Any which way you slice the data, a lot of campaign money goes for paying the costs associated with fundraising, Glavin notes. Presidential campaigns spend at least 30 cents of each dollar they raise to cover the cost of chasing additional contributions, he maintains.

Ad buys add up, too. “TV ads remain a huge line item for campaigns, Glavin says. “It can be hard to quantify this via FEC data.”

But Adimpact, an advertising analytics firm, tries to do exactly that and offers its take on political expenditures for broadcast, cable, radio, satellite, digital and CTV. “Presidential spending is projected to receive $2.7 billion in political ad spending this cycle” the company says.

Google and Meta, the two largest online platforms, have collected at least $248 million for presidential campaign ads this cycle, according to a report from the Wesleyan Media Project, the Brennan Center and OpenSecrets.

Overhead accounts for a lot of the outlays of presidential campaigns, which Glavin characterized as “all the things that make a campaign run—rent, salaries, travel, rallies.”

Combing the FEC campaign spending data, Luckbox also saw expenses that included taxis, fuel, email, meals, hotels, postage, shipping, Google, G-suite, parking, catering, payroll, bank fees, membership dues, food and beverage, internet service, database management, ad production, and compliance consulting. We could continue our list, but you get the idea.

One entry that’s ubiquitous on the data sheets seems particularly puzzling. Repeatedly, the campaigns list “contribution refunds” in varying amounts. We’d like to find out what that’s about, but we’ll save that inquiry for another day.

In the meantime, you may be wondering exactly who collects the billions spent running to run the country. The answer is most of the vendors specialize in politics and aren’t well-known in the world at large. You probably haven’t heard of them unless you’re a veteran high-level campaign official.

The five vendors that have received the most money from Democrats, and the amount they collected by the beginning of October, are MissionWired, $57 million; RWT Product, $44 million; Actblue, $43 million, Gambit Strategies, $34 million; and Canal Partners Media, $32 million.

Top five for Republicans have been Targeted Victory, $75 million; Target Enterprises, $69 million; AxMedia, $46 million, In Pursuit Of, $40 million; and Del Ray Media, $39 million.

But any numbers associated with political campaigning can seem slippery.

The uncertainty of campaign finance

Take the example of internet ad spending. The $248 million for presidential campaigns cited earlier comes with several caveats and the admission that it understates the real total. Wesleyan researchers say they looked into only the entities that spent $5,000 or more and that organizations buying the ads kept the identities of about half their donors secret.

That’s the type of “dark money” that clouds any attempt to trace campaign spending. It hinges on the difference between PACs and Super PACs.

The first variety of funders, PACs or political action committees, fall into two categories: One for groups established and run by corporations, labor unions, membership organizations or trade associations. These committees can solicit contributions only from individuals associated with the organization. The second category is for PACs that can accept contributions from the general public.

PACs are required to disclose the identities of their donors and are subject to limits on contributions. Super PACs, however, don’t have to share the names of contributors and there’s no limit to the size of contributions.

So, Super PACs inject huge sums of money into the political process from unknown sources, earning their funding efforts the nickname “dark money.” That sobriquet also applies because Super PACs aren’t allowed to work directly with campaigns or parties and thus spend their money in ways the public might not know about.

It’s why an inquiry into how presidential campaigns spend their money raises more questions than it answers.

Ed McKinley is Luckbox editor-in-chief.