Yes, This is Stagflation

But it STILL MIGHT BE transitory

Something new happened in the 1970s and it’s apparently coming back to haunt the nation again. It goes by the name “stagflation.”

The word, a portmanteau of “stagnant” and “inflation,” stands for slow growth (stagnation) combined with high prices (inflation).

It creates a host of problems for central banks: Do they hike rates to stem inflation and risk even slower growth? Or do they cut rates to spur the economy and risk fueling inflation?

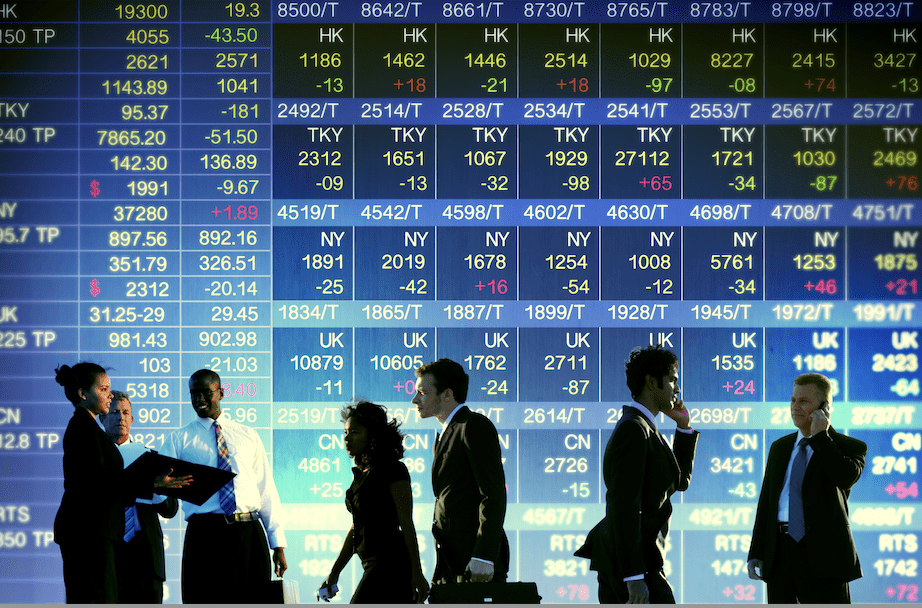

There’s no right answer. What’s more, stagflation hasn’t happened very often, so there’s no playbook to go by. But the decisions central bankers make about stagflation produce market winners and losers.

The “Me Decade”

Some remember the 1970s as the “Me Decade”—a time when Americans cast aside the social movements of the ‘60s and refocused their attention on their own personal well-being. Some prefer to forget the ‘70s altogether because of the decade’s economic tribulations.

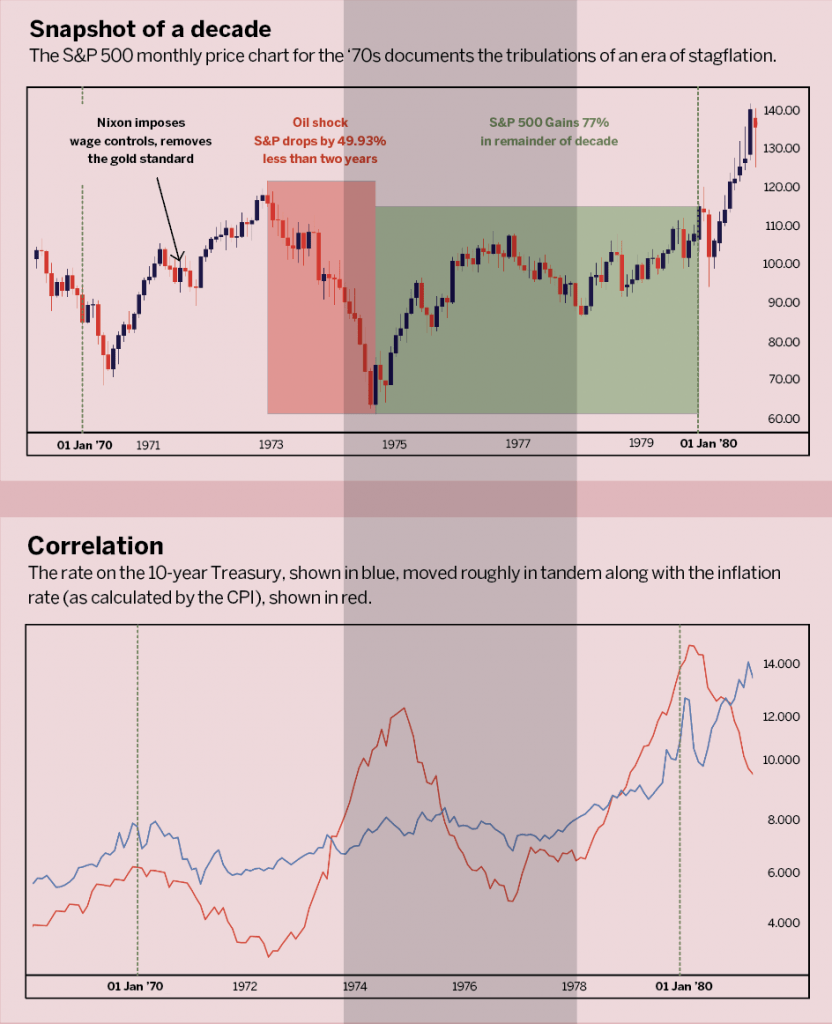

Inflation was already high when the decade began, running 6% for 1970 and 4% for 1971. To stem those price increases, President Richard Nixon instituted wage and price controls and suspended the gold standard in August 1971.

But inflation climbed higher when OAPEC—the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries—embargoed shipments of petroleum and thus created the 1973 oil crisis. The price of gasoline skyrocketed and motorists lined up to fill their tanks. Stations posted signs when they ran out of gas.

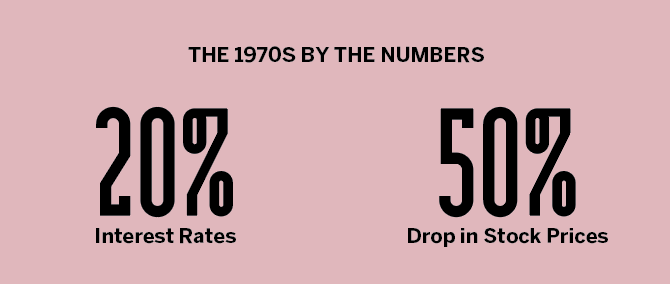

Stock prices plunged, losing nearly 50% of their value in 20 months. Interest rates rose to nearly 20%. Listlessness prevailed.

Enter, Paul Volcker

President Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank in the summer of 1979. Home mortgages were carrying double-digit interest rates as inflation grew by about 1% per month. The dollar was considered nearly worthless.

The prevailing wisdom was that paper assets—currency, stocks and bonds—were terrible stores of value. Instead, many viewed commodities as optimal investments because they wouldn’t be as badly debased by a weakening currency.

Stocks underperformed, largely because they were denominated in dollars, a currency that didn’t inspire confidence among investors at the time. Metals and commodities did well because inflation didn’t erode their value.

Before Volcker, the Fed was run by Arthur Burns, whom Nixon appointed in 1969 with one directive: No recession. Nixon even made a remark to Burns about “the myth of the autonomous Fed.” So the central bank kept interest rates low, and that helped Nixon win re-election in 1972.

Burns followed Nixon’s directive and ran expansionary monetary policy for much of the decade despite lackluster results. After he left office, Burns said it was “illusory” to expect central banks to curb inflation, implying that the political pressure behind low rates and expansionary policy was too much for a central banker to resist.

Six days after Burns cast doubt on the idea of the Fed’s independence, Paul Volcker made a radical announcement: The bank would target the volume of bank reserves in the system, as opposed to interest rates, allowing rates to go as high as needed to reduce reserves. The move was designed to shield Volcker from political pressure because he was instituting a formula to fix the problem of stagflation instead of making a subjective decision on how to adjust interest rates.

Volcker expected interest rates to spike because the system was awash in excess credit. The Fed Funds rate jumped from 11% in 1979 to 19% in 1981, causing a recession. Volcker knew what had to be done and devised a way to gain enough political cover to do it. Along the way, Jimmy Carter lost his bid for re-election to Ronald Reagan in 1980.

By 1983, inflation had moved back below 4%. In 1986, it fell to 1.9%. Volcker’s plan had worked. It induced a mild recession to temper the excess credit, which enabled Americans to focus on consuming rather than hoarding or guarding their investments against runaway inflation.

Stagflation today

The greatest similarity between today’s economy and that of the ‘70s is artificially low interest rates. The Fed holds rates down to prevent recession and drive economic growth. That isn’t really the Fed’s job, as the bank has two mandates: price stability and employment.

Congress should be responsible for economic growth, but after the global financial collapse of 2008, the Fed had to step in with multiple rounds of quantitative easing (QE)—the policy of buying longer-term securities on the open market to increase the money supply and encourage lending and investing. That put the responsibility on the central bank, and it’s stayed there.

Some feared QE could bring the return of runaway inflation because the bank was looking to flood the system with excess credit. When that didn’t happen, the Fed continued to indulge in QE, covering for politicians who were unable or unwilling to risk assuming responsibility for the economy.

When COVID-19 struck, the Fed went back to the emergency playbook to institute carte blanche lending that, like in the ‘70s, left the financial system awash with excess credit. As in the ’70s—but unlike the period after the global financial collapse—inflation has started to pick up.

With inflation rates moving over 6% throughout 2021, the inflationary aspect of stagflation is already in place. While growth for 2021 has been relatively strong, the question remains: How much of that growth is pandemic-related bounce-back and how much is legitimate and organic?

Real rates have been negative for more than a year, and the Fed wouldn’t dream of hiking them anytime soon. The Fed has warned that it may raise rates one time in 2022, but if history is any guide, it will back down unless the economic backdrop is absolutely perfect for a “lift-off” in the second half of next year.

So, yes, the nation has a form of stagflation today, although it may last for only a few years.

The stagflation investor

The S&P 500 produced a return of 19.85% in the ‘70s, with investors valuing precious metals and commodities much more than paper assets. Much of the pain in stocks was relegated to the bear market that ran from 1973-1974 and accounted for a 50% loss to the index. But that’s when the oil shocks were happening as OAPEC constrained supply—clearly an extenuating factor.

The rest of the decade was more stable, with the S&P 500 returning 77% from

the 1974 low into the end of the 1980 open. Inflation ran rampant, so there’s not a strong correlation between

weak stock prices and strong inflation, although precious metals did easily outperform stocks.

Stocks aren’t necessarily a no-fly zone during stagflation, but sector and style of equity become important considerations given the macroeconomic backdrop.

Bonds in the ‘70s

Interest rates were elevated and continued to climb as the Federal Open Market Committee led by Burns failed to temper rising prices. But, real rates were negative much of the time, so holding a bond to clip the coupons was a losing proposition.

With the prospect of higher rates, bondholders faced deeper depreciation of principal (rates and prices move inversely)—a confounding scenario for anyone looking for returns through Treasuries or other fixed-income investments.

Precious metals in the ‘70s

The prevailing economic wisdom during the stagflation of the 1970s was that investors should avoid paper assets and seek commodities, and it was a very good decade to be long gold. After starting January 1970 at approximately $35 per ounce, gold prices pushed up to $533.60 by the end of the ’70s. That amounts to a return of 1,426.75%.

A wild January 1980 saw prices top out at just under $900 per ounce before reversing and falling by 66.29% into the summer of 1982. It was no coincidence that the gold trend reversed as Volcker started to hike rates. This pivot may offer lessons for market participants now.

Silver outpaced gold in the ’70s, albeit by a minimal margin with silver putting up 1,446.96%, versus gold’s 1,426.75%. Like gold, silver spiked and burned shortly after the 1980 open as Volcker kicked rates higher.

Bitcoin’s rampage

The creation of bitcoin was still far in the future when the ’70s ended, but given its impact in markets today, the original cryptocurrency bears mention. Many speculate that bitcoin is the world’s new inflation hedge. Given the near-term performance of gold and silver, with both largely underperforming over the past 12 months, that idea seems to be gaining traction.

Cryptocurrencies in general are interesting, but let’s focus on bitcoin because the limited supply of 21 million coins can have a monumental impact as an inflation hedge. Bitcoin can never surpass that number. As inflation erodes purchasing power, the value of one bitcoin will always be one bitcoin, and a depreciating dollar can make that an even stronger equation for holders of the cryptocurrency.

Notably, gold prices have remained relatively weak since topping out last August when bitcoin was trading below $12,000. As inflation has ramped up recently, gold has continued to show weakness while bitcoin has jumped by 80% from the June low and a whopping 880% from last year’s low. Perhaps there is a new inflation hedge in the equation.

Today’s takeaways

Would Volcker be able to pull off his strategy today? That’s worth pondering as a social media-connected world with financial markets on watch 24 hours a day is unlikely to let someone like Volcker implement a strategy that would cause a recession. The public scrutiny would be too much, and as with the relationship between Fed chair Jerome Powell and former President Donald Trump, politicians continue to influence central bankers who are supposed to operate with independence.

Volcker’s strategy saved the Fed’s independence, and he probably saved the dollar, too. But the cavalcade of central bankers that have come in his wake has seemed prone to honoring public sentiment and carrying out the directives of elected officials. That makes the prospect of another Volcker-like central banker doing what needs to be done a distant prospect.

So, position accordingly.

James Stanley, a senior strategist for DailyFX, helps direct educational content and produces articles and web seminars. @jstanleyfx