How China “Controls” Inflation

The Middle Kingdom’s command-style economy is keeping consumer prices artificially low. It can’t last.

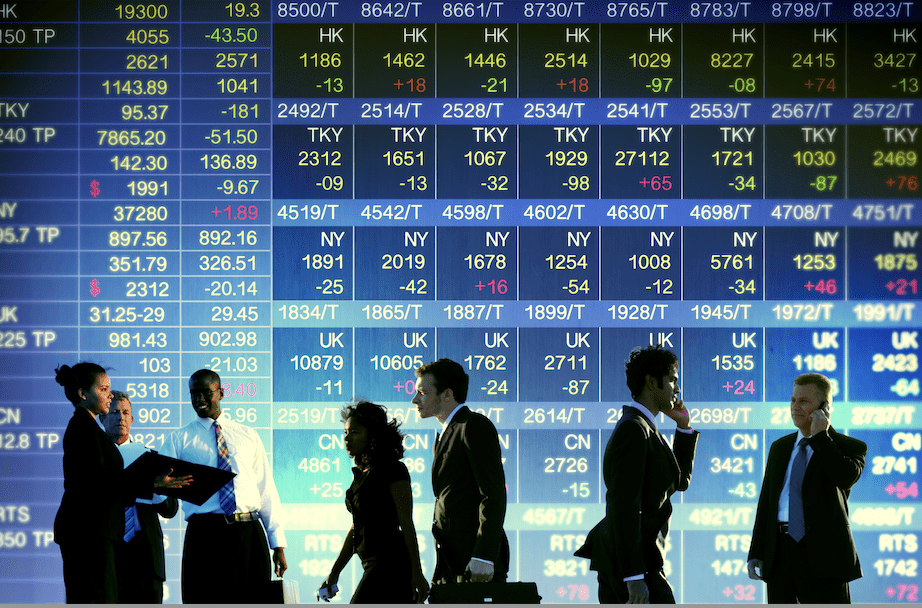

As most of humanity grapples with inflation, China finds itself in an unusual position. Consumer prices have barely inched up there, while the cost of doing business has increased substantially.

The divergence, rooted in the nature of the Chinese economy and the country’s system of governance, demands a closer look.

The price of household goods in China—as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—came in at 0.7% in September and is expected to average about 1.4% for all of 2021. That’s remarkable compared with the 6.2% CPI for the year in the United States.

But that doesn’t tell the whole story.

In China, the Producer Price Index (PPI) has skyrocketed this year to nearly record highs. The PPI records prices of industrial goods produced for the domestic market, a key metric in an industrial country like China.

By August, the PPI in China rose 9.5% compared with a year earlier. That’s the third highest reading since the Chinese PPI was first published in 1996. It was higher only in July and August of 2008, when it reached 10% and 10.1%, respectively.

Taken together, the CPI and PPI suggest inflation has taken hold in China but indicate that businesses, not consumers, are shouldering the burden.

China’s command-ish economy

In the United States, the difference between the CPI (5.4%) and PPI (8.6%) seems a lot less extreme.

That balance suggests U.S. businesses are absorbing some of the shocks of rising prices but passing along part of the problem to consumers. Chinese businesses are apparently bearing a much bigger load.

That disparity arises because China doesn’t operate as a free-market economy. Instead, it mixes free-market principles with characteristics of command economies. Ultimately, China leans toward the latter, which means the government exercises heavy control over how the nation uses land, capital and resources—in other words, just about everything. In the United States, the private sector holds sway to a great degree.

So in China, the government decides—to some degree—who pays more when prices are rising. Moreover, it has been cracking down this year on what some see as the excesses of free enterprise, calling upon domestic businesses to embrace “common prosperity,” as opposed to pure profits.

And because of the country’s totalitarian system of governance, Chinese leaders can order factories and businesses not to raise consumer prices, which is undoubtedly what transpired this year.

This arrangement causes problems because most Chinese businesses are competing in global markets for raw materials and other commodities. After all, the Chinese government can’t order foreign suppliers to charge lower prices—especially in highly efficient markets where demand outweighs supply.

Hence, the current inflationary environment is forcing Chinese businesses to operate on

thinner profit margins—if not at a loss—and that’s not sustainable.

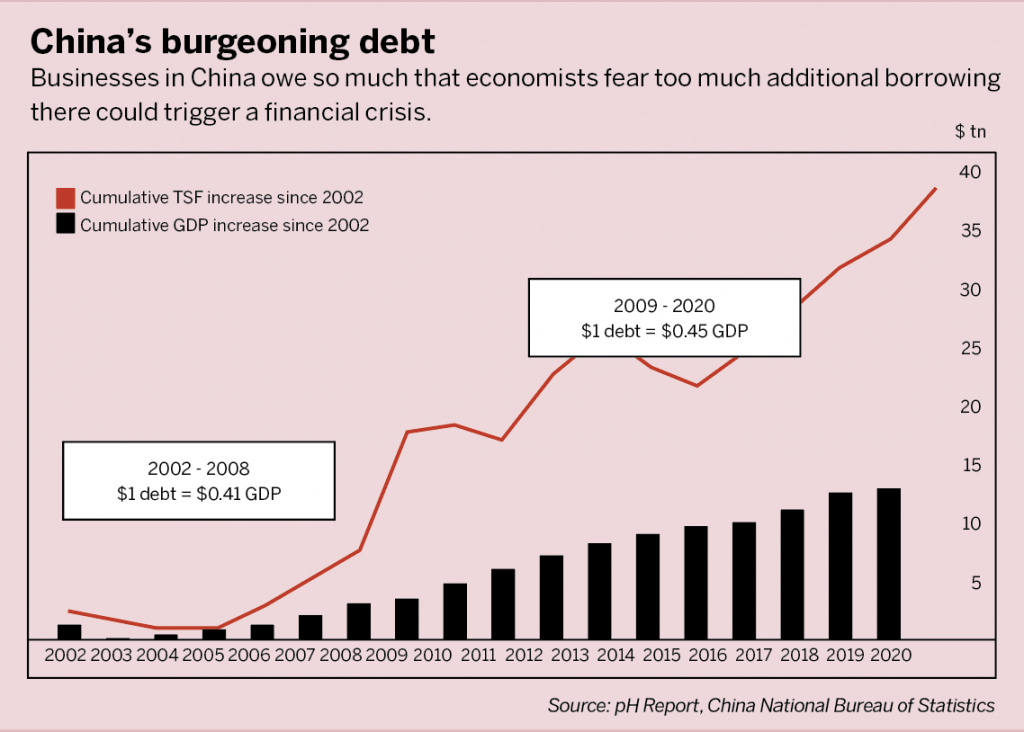

Chinese corporate debt is already extremely high, which means increased lending would aggravate an already tenuous situation. The challenge of rising costs, combined with a slowdown in corporate lending, might explain why some parts of the Chinese economy are starting to exhibit signs of distress.

Chinese property developers have been under pressure in recent months as they struggle to service mounting piles of debt. The China Evergrande Group, one of the most often cited examples of a company circling the drain, reportedly has liabilities in excess of $300 billion.

Economists warn that onerous debt in China could trigger a financial crisis. That fear is based on red-lining levels in the Chinese ratio of debt-to-gross domestic product.

The debt-to-GDP ratio measures a country’s total debt (government, corporate and consumer) relative to what’s produced in the country. That metric is commonly used to evaluate a country’s financial health and ability to make good on its debts.

In the last quarter of 2019, the Institute of International Finance estimated the public debt-to-GDP ratio in China at 302%. And by May of 2020, it had risen to an estimated 318%—the largest quarterly increase on record for the Middle Kingdom.

For context, the World Bank has characterized debt-to-GDP ratios above 77% as suboptimal and warned that the resulting debt service could threaten a country’s economic potential. By comparison, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is roughly 98%, based on estimated net public debt of $20.3 trillion divided by estimated GDP of $20.6 trillion.

With Chinese corporate debt already high, the government probably wouldn’t want to combat rising inflationary pressures with additional lending.

Those hard realities may help explain why the Chinese stock market has been under pressure in recent months. For reference, the KraneShares CSI China Internet Exchange-Traded Fund (KWEB) is down more than 50% from its 52-week high, currently trading at about $50 per share.

With the system straining under these pressures, it seems likely the Chinese government will soon be forced to capitulate and allow manufacturers to pass along a higher portion of rising costs to consumers. In fact, those changes may already be in motion.

The price of soy sauce

One sign of a shift in the Chinese inflation story can be tied back to one of the country’s most iconic inventions: soy sauce.

Soy sauce, a staple in every Chinese household, might be compared to table salt in the United States—it’s ubiquitous. Soy sauce, brewed by fermenting soybeans, grains, mold cultures and yeast, is believed to have been created in China 2,200 years ago.

In October, one of the best-known soy sauce manufacturers in China, the Foshan Haitian Flavouring and Food Company, announced it was raising prices by about 7% across the board. Besides soy sauce, Foshan Haitian also produces and distributes vinegar, chicken stock and cooking oils.

The price of household goods in China is expected to rise about 1.4% for all of 2021, compared with 6.2% in the United States.

The company cited the rising cost of raw materials, transportation and energy in the announcement.

With soy sauce such a staple in China, it appears that the government has finally agreed to pass on some portion of inflation to consumers. Foshan Haitian could not have made such a move without the government’s tacit approval.

So cracks are now forming in the protective shield for consumers, who will apparently be shouldering a larger share of the inflationary burden.

That shift should help alleviate some of the pressure building in the Chinese business sector. But the government will still need to resolve the country’s long-ignored problem of corporate debt or else international equity and debt markets might do it for them.

Andrew Prochnow, an avid, longtime options trader, has written extensively about professional tennisand contributed articlesto the Bleacher Report and Yahoo! Sports.