How Much Does the U.S. Really Spend on NATO and Foreign Aid?

The U.S. is paying less than you might think to defend Europe, and NATO members are stepping up their contributions

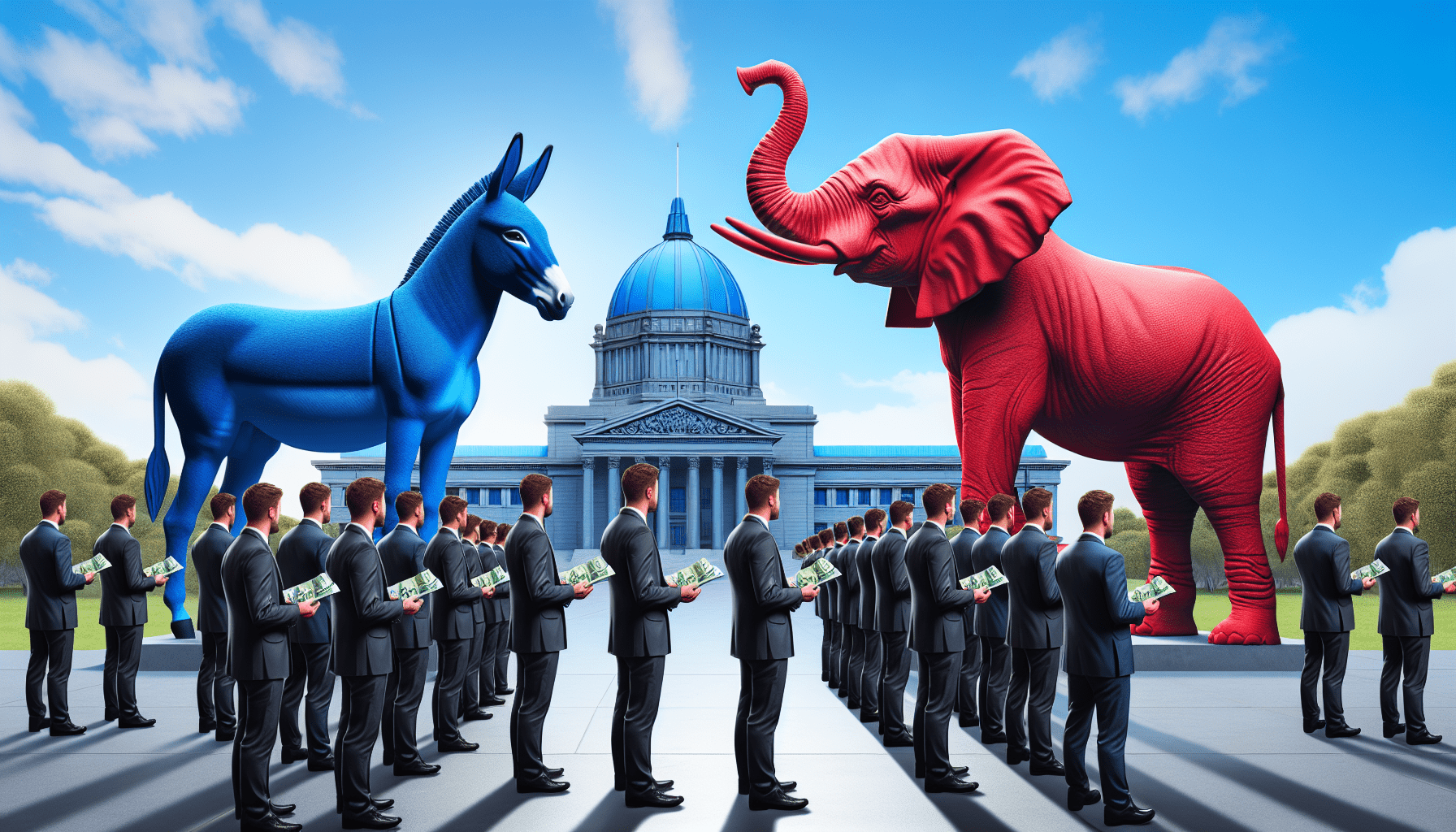

Some Americans denigrate our European allies for supposedly failing to shoulder their fair share of the cost of NATO. Truth be told, the U.S. paid $567 million or 15.8% of NATO’s $3.5 billion budget last year.

But isn’t the U.S. still paying too much? Maybe not. It happens that 23 of the organization’s 32 members are quietly meeting or even exceeding the alliance’s goal for contributions.

NATO set a goal in 2006 of persuading every signatory to the pact to assign at least 2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on its own defense. In 2014, the group declared every country should “aim to move toward the 2% guideline within a decade.”

Ten years ago, only three countries (the U.S., UK and Greece) were spending more than 2% on defense. But that was then. Now, NATO members are spending an average of 2.7% of their domestic GDPs on defense.

Poland leads the pack by earmarking 4.1% of GDP for defense spending, according to a list from Statista, an online platform that gathers and visualizes data. Poland is followed by Estonia in second place at more than 3.4% and none other than the United States is in third with a little less than 3.4%.

Latvia is in for 3.1%, Greece for 3.0% and Lithuania for 2.9%. Finland and Denmark are both at 2.4%; the United Kingdom and Romania, 2.3%; North Macedonia, Norway and Bulgaria, 2.2%; Sweden, Germany, Hungary, Czechia, Turkey, France and the Netherlands, 2.1%; and Albania, Montenegro and Slovakia, 2.0%.

The countries just a bit behind are Croatia, 1.8%; Portugal, 1.5%, Italy, 1.5%, Canada, 1.4%; and Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Spain, 1.3%. So, even the countries trailing the guideline aren’t too far off the mark.

But what ‘s the point of that spending? The 12 original members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization formed the military alliance in 1949 to defend Europe against an attack by Russia, or the Soviet Union as it was called in those days. The agreement was that an attack on one was an attack on all.

The horrors of World War II were still fresh in the minds of the officials who signed up for the organization, and their efforts to keep the peace have paid off. Over the years, more nations joined, and the organization helped prevent the Cold War from turning into a shooting war.

But all this talk about contributing funds to defend allies made us wonder how much the U.S. was spending on other assistance to friends around the world. Let’s take a look at that, too.

U.S. foreign aid

Advocates of an “America First” foreign policy would have you think the nation spends generously on aid to other countries, but our largess is actually quite limited.

The United States allocates about 1% of the national budget to foreign assistance, according to the Brookings Institution a center-left think tank. That came to $58 billion in 2022 and $63 billion last year.

Can we afford even that much? Probably. It’s less than 0.33% of the gross domestic product, Brookings says. The U.S. GDP is expected to surpass $29 trillion this year, as forecasted by the International Monetary Fund.

That’s about a fourth of the world’s $110 trillion production of goods and services and far outstrips China’s second-place GDP of $18 trillion. The U.S. produces more than all the countries of the European Union combined, which is expected to total $19 trillion this year.

So, even 0.33% of something as big as the U.S. GDP means a lot when it’s spread over the planet.

Small slice of a big pie

The aim of that spending is altruistic if you believe the U.S. State Department’s website. It’s claimed there that in 2022 economic aid accounted for 86% of foreign aid and military aid was 14%.

Yet somehow the countries receiving the most money from the United States are at war or preparing for war. Ukraine was by far the biggest recipient with more than $12 billion and Israel came in second with over $3 billion. Those figures are for 2022, so the totals have probably climbed much higher in the face of escalating armed conflicts.

A combination of civil war and drought plague the third-largest recipient of U.S. foreign aid. Ethiopia, the second-most populous country in Africa with 133 million residents, accepted $2.2 billion in help from us in 2022.

However, the U.S. Agency for International Development halted some types of assistance to Ethiopia for a time last year because of what may have been the largest food-aid theft in history.

But back to the ledger of foreign aid recipients. Scrolling down the list of the biggest beneficiaries, we see in Afghanistan occupied fourth place in 2022 with nearly $1.4 billion in aid. It received that funding despite the American withdrawal from the war there in August 2021.

Countries in the next three spots on the list were all Mideast nations vital to U.S. interests. Yeman and Egypt each received nearly $1.4 billion, and Jordan

got well over $1.3 billion. (Yes, you might consider Egypt to be African, but it’s certainly a player in the Middle East.)

And the next batch of countries, those numbering eighth through 13th on the list all occupy spots on the African continent and all received about $1 billion in aid. They were Nigeria, Somalia, Kenya, Congo and Sudan.

The 14th through 16th spots included another Middle East country, namely Syria, and two from Africa—Uganda and Mozambique. Continuing down the list from there, we see South American nations begin to crop up among the countries in the Middle East and Africa.

One of the entries we found a bit surprising was Canada at 105th place with $32 million in U.S. foreign aid. Isn’t Canada faring at least as well as the U.S. these days? Well, not exactly if you measure well-being by “adjusted net national income per capita.”

That’s something calculated by Statista, a Germany-based online platform specializing in data gathering and visualization. It found the United States fourth in per capita income at $59,000 and Canada 17th at $42,000.

As an aside, Luxembourg tops the list at nearly $78,000 in per capita income, followed by Norway in second place with almost $70,000 and Switzerland in third with well over $69,000.

But continuing down the list, we came across outliers, anomalies and perhaps some mistakes.

Germany came as a surprise, occupying 124th place with $7.4 million in assistance. Its per capita income of nearly $43,000 puts it in the 16th spot among nations. Couldn’t we just buy more Audis, BMWs, Mercedes, Porsches and Volkswagens instead of sending aid?

And Japan? It’s questionable whether our help’s needed in the Land of the Rising Sun, the nickname the country got because of how the dawn breaks in China. But just the same it collected $1.5 million in aid, placing it 150th among countries.

Then there’s the matter of aiding the enemy. The U.S. extends at least a little foreign aid to avowed adversaries. The People’s Republic of China, the giant that’s menacing Taiwan and bullying everybody else in the South China Sea, got $2.2 million, placing it 141st. Russia, the aggressor trying to gulp up Ukrainian territory, accepted $1.7 million, putting it 144th.

And how about Cuba? It’s the country that scared the bejesus out of the U.S. in 1962 by allowing Russia to take up positions on its soil and aim missiles at us from 90 miles away. A few of us are old enough to remember the maps showing where the radiation would drift. Well, Cuba came in at 125th with $6.8 million in U.S. aid.

Although Greenland’s a lot friendlier to the U.S., it still seemed like $3.4 million was a lot of aid for a place with a population of 56,000 even if it is the world’s largest island. But I did the math and realized that was only a little over $60 per person. It’s as though we took them all out to dinner.

South Korea, which is winning acclaim in the U.S. for the cars and the movies it’s sending here, got $239,000 and took 169th place. The portion of Korea north of the 38th parallel, which is now aiding Russia in its war on Ukraine, somehow captured $264. Perhaps it was just a clerical error or maybe a package delivered to the wrong address. Anyway, that made South Korea the country that received the smallest amount of aid and placed it 179th on the list.

So, there’s a glance at who got what. Let’s think now about why.

Guns or butter

Broadly speaking, aid falls into two categories: economic and military. Sifting through the data on which countries received which type of assistance often confirms what intuition might suggest.

Estonia, for example, a smallish Eastern European nation menaced by scary neighboring Russia, received close to $142 million in military aid and a scant $1 million in economic assistance.

On the other hand, Burundi, a small, land-locked Sub-Saharan African country with an economy based largely on subsistence agriculture, was granted $141 million in economic help and nothing for military preparedness.

Those patterns tended to remain in place around the world, with countries near Russia receiving military aid and those in Africa getting economic help.

But someone has to sort out which kind of aid makes the most sense for any particular country. So, who decides? Perhaps its people at the U.S. State Department.

Here’s the official word: “The Office of Foreign Assistance is responsible for the supervision and overall strategic direction of foreign assistance programs administered by the U.S. Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).”

The secretary of state, one of the loftiest offices in the president’s cabinet, delegates responsibility for overseeing foreign aid to the deputy secretary for management and resources and the director of foreign assistance.

But those officials and that department can’t distribute funds they don’t have. Clues to how the Trump administration might handle foreign aid may reside in the writings connected with Project 2025, the right-leaning Heritage Foundation’s proposals for a Republican overhaul of the federal government.

Project 2025 characterizes the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund as organization that “espouse economic theories and policies that are inimical to American free market and limited government principles.” Those entities and other international players “regularly advance higher taxes and big centralized government,” Project 2025 says.

The new Trump administration’s relations with Russia and North Korea could also shift how and where the U.S. distributes military aid. Trump has pledged to end the war in Ukraine quickly, and he’s made statements indicating he may not have a strong commitment to the NATO alliance.

But whatever happens, the money the United States spends to assist other countries seems likely to remain a minuscule part of the budget and the GDP.

Ed McKinley is Luckbox editor-in-chief.