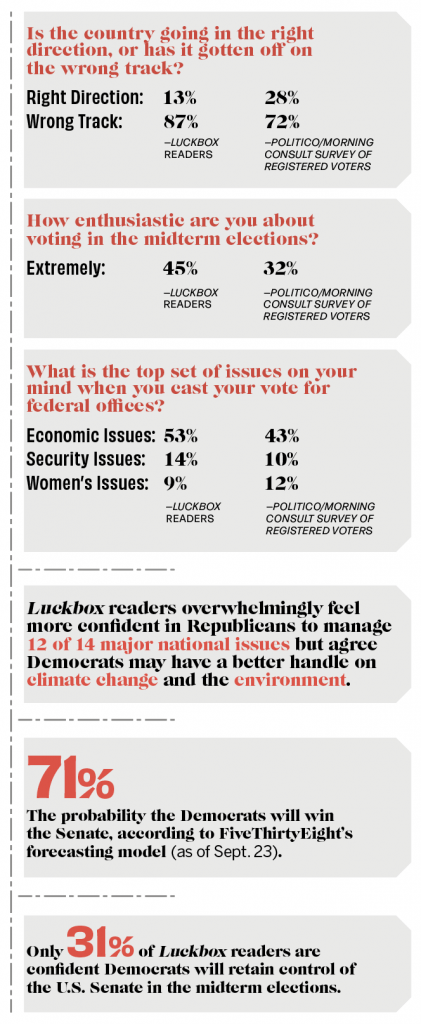

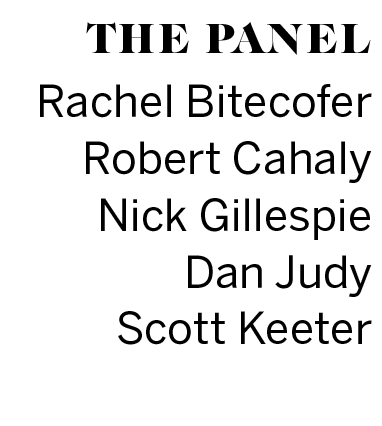

The Midterms Roundtable

Politicos and pollsters are split on a lot of issues, but they’re PREDICTING some surprising results in the upcoming balloting.

What issues are motivating Americans to vote in the midterms?

Dan Judy: What we’re seeing in the polling, and this is something that hasn’t changed, is the economy and inflation are the absolute biggest issues for voters. The Dobb’s decision has energized Democrats. [In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and revoked the constitutional right to abortion]. While the environment is still favorable toward Republicans, it’s gotten slightly less favorable over the last few months. Republicans are the proverbial dog who caught the car on Roe v. Wade—they have had 50 years trying to overturn this, and now that it’s overturned it feels like they haven’t thought very much about where to go next. They’re being defined by a position that very few actual Republican voters—and not that many Republican elected officials hold—which is an abortion policy that allows no abortions in any circumstance ever. The Democrats have worked very hard to define them that way. They haven’t done a great job of laying out a more moderately pro-life policy. But the economy and abortion are the top issues right now. When you pit them against each other, the economy is still most important for most people. But the abortion issue has sort of energized Democratic turnout and enthusiasm.

Rachael Bitecofer: The main issue that will define this cycle is the evisceration of Roe. It changed the fundamentals of the cycle in which the midterm helped the Republican Party as the out-party. It’s a long-standing, empirically robust pattern in American politics. It would have been a pattern that we probably would have seen play out to some degree had it not been for the Roe evisceration that’s upset everything. It has inflamed negative partisanship, which is not just hate of the other party as people like to think about it. It’s a fear and threat response to the other party. The in-party makes the out-party’s voters feel threatened, because they control the levers of power, and they use them to do things. That’s why the midterm effect has always benefited the out-party. This time, though, because of Roe and these trigger laws, there’s this massive threat reaction in the other part of the coalition. What we’re now looking at are two different waves that will run into each other. It’s going to make predicting this outcome very difficult

Robert Cahaly: Inflation, crime, the border, and the general frustration with how the federal government handles things are the driving main issues that are affecting people. Others will be abortion related to some of the state’s reactions to Dobb’s decision. One [issue] I see with the same intensity is student loan forgiveness, which I see creating great intensity on the other side.

Nick Gillespie: I don’t think you can get away from the basic, economic direction of the country. I think everything is an epiphenomenon of that. There’s no question that things like foreign policy and what we saw in the early 2000s in the wake of 911, then the subsequent launching of the War on Terror, really have an impact. I think even questions like abortion are not as important as unemployment, inflation and whether the country is going in a good or a bad direction. Typically, polls before the Dobbs decision, showed that maybe 20% of people really put abortion rights as one of the absolute top issues they would vote on, and they were split evenly between pro- and anti-abortion forces. I don’t know that it will be a particularly strong issue for people. Younger people are split and vexed on the issue, and they don’t show up in large numbers. Because this is a midterm election, there is not a galvanizing candidate like a Barack Obama or in a negative way, a Donald Trump, to really get the youth vote out.

Should pollsters correct their process if they haven’t already done so?

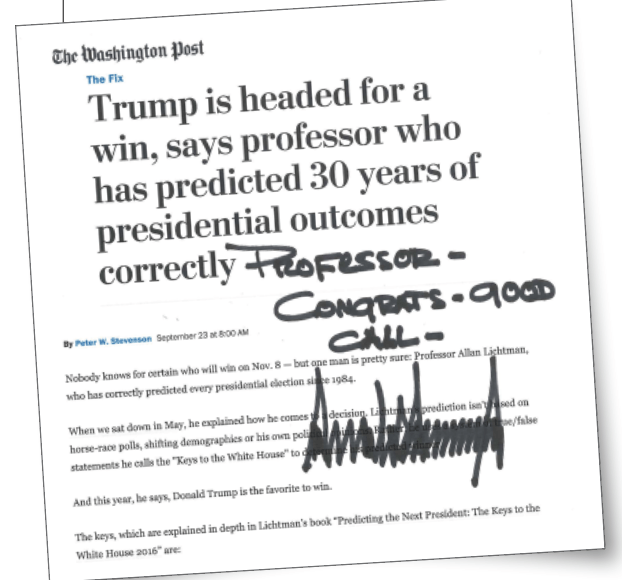

Scott Keeter: We did think after 2016 that we might have found a smoking gun, which was that some pollsters were not adequately accounting for the educational composition of their samples. One of the changes in American politics in the past 10 to 20 years has been that less-educated white, non-Hispanic Americans have become more conservative and more supportive of Republicans. If your samples underrepresent less-educated people, which almost all survey samples will in their raw form, then you have to address that statistically through the process of weighing the data. But it is a very difficult problem if a particular type of person, by their attitudes, is less willing to be interviewed. Because there’s almost no way to adjust for that in a direct fashion other than just putting your thumb on the scale, which maybe pollsters are tempted to do.

Cahaly: Republicans are about five times as hard to get to participate in polls as were Democrats—so you have to go the extra mile. Most [polling] groups don’t acknowledge a simple fact—people are hesitant to take polls, and people lie. If you can’t acknowledge that, then you can’t really get to the truth.

What races are you following in the midterm elections? Why?

Judy: On the Senate side, the Republicans can’t afford to lose any seats they currently hold. That’s one of the reasons they’re in a little bit of a bind because some of the seats they currently hold are leaning Democratic, or many are tossups. You have to look at Pennsylvania, Ohio, North Carolina—the Republicans can’t afford to lose any of those. The Senate races generate more interest, partially because there are fewer races so it’s easier to focus. The candidates, especially on the Republican side, are kind of unorthodox and that makes them a little more interesting to follow. The Republican takeover of the House—I don’t want to say it’s a foregone conclusion, but it would be a major upset even now for the Republicans not to take the House. In the Senate, the control is very much in the air, it could go either way, so I think that’s one of the reasons why the Senate races tend to get a little more attention. Nevada is one of the better opportunities—it hasn’t gotten quite as much opportunity or quite as much attention as Georgia and Arizona, partially because the candidate there, Adam Laxalt, is a little more orthodox and not quite out there like a Herschel Walker [Georgia] or Dr. Oz [Pennsylvania]. Nevada, it’s a pretty swingy state, so that’s probably the Republicans’ best opportunity for a pickup.

Gillespie: Regarding Senate races, I’m interested in the Peter Thiel candidate in Arizona, Blake Masters, and J.D. Vance in Ohio. I’m curious to see how they fare because they’re doing less well than they should be, given those states and their party affiliation. They represent a particularly toxic version of populism. If we see either of them lose, or barely squeak by in victory, it shows that populism of a Trumpian variety is kind of a paper tiger, which I think would be a good outcome. Anti-immigration people and people who are anti-free trade might be able to win by attracting Democratic votes in certain instances and Republican votes, but in the long haul, those are loser positions.

Cahaly: There are races that people don’t think could flip, but we think keep your eye on Patty Murray in Washington state. I think that’s one that needs to be very carefully watched—there’s a lot of frustration up there, and she’s running against a very good candidate [Republican Tiffany Smiley]. We think the Republicans are going to be victorious in Nevada in both the Senate and governor’s races, but watch the Patty Murray [Senate] seat, and possibly the Colorado Senate seat, [where Republican Joe O’Dea is challenging Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet]. But we see Murray a little more on the bubble. We also see Republicans in most trouble with Ron Johnson [of Wisconsin] because I think this is an anti-incumbent year and so I think for incumbents to win, they have to be particularly well-liked and particularly well attentive to the needs of their state. We think Herschel Walker [of Georgia] will win and we don’t think that’s a surprise—better than 50% that Herschel Walker wins. Same thing in Arizona—even money. We don’t think J.D. Vance has any trouble. We think North Carolina is not really hotly contested— it’s a tight margin but it’s the same kind of tight margin Republicans will continue to win by in North Carolina. We think [Republican Blake] Masters has even money chances of winning in Arizona [against Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly] and probably the same thing in New Hampshire with [Republican Don] Bolduc [facing Sen. Maggie Hassan]. They’re even—not a surprise if they win and not a surprise if they lose. Washington state would be a surprise and Colorado would be a surprise.

What voting blocks are you watching and what shifts are you anticipating?

Judy: We’re looking at college-educated voters in the suburbs, especially suburban women. Those were the voters in the 2018 midterms, and also in 2016, and 2020 presidential elections who really sort of swung from being traditionally Republican to voting for Democrats, and that was all driven by Donald Trump. With Trump not on the ballot, the question is how many voters return to Republicans. Ideologically and culturally, they might be a little more center-left. A few months ago, those voters would be swinging back pretty strongly toward Republicans. In the wake of Dobb’s, that’s been muted a little bit.

Hispanic voters have started to take more steps toward Republican candidates over the last couple of election cycles. Republicans still have a long way to go among many Hispanic voters. Still, they seem to be gaining in strength there, especially with many big races in Texas and in Florida, where you have a big concentration, and on the Senate side in Nevada and Arizona. If the Republicans could improve their standing among the Hispanic blocks in those states, it would give them a much bigger chance to swing those Senate seats.

Cahaly: We’re watching parents with school-aged children because some of them seem to be the most frustrated after what they have witnessed, whether it was mask mandates or vaccine mandates or some of the things they think their children were taught outside of their belief system. They got very, very engaged in Virginia. Frankly, many of that crowd is engaged now, and they’ve been pouring into school board races and paying attention. It’s just a whole bunch of average moms and dads who used to be a little too busy for politics to realize that it’s more important than maybe it had been to them in the past. We’re watching to see how close that turnout mimics what we saw of Virginia, as a percentage, because it usually is not a huge percentage of a midterm turnout.

Gillespie: It’s particularly tough to know because I think turnout will be lower than people expect. We’ve had a couple of recent midterm elections that have drawn pretty big crowds. I suspect that’s not going to be as big as we’ve seen in recent midterms. I think in 2024, the biggest shifts you’re going to see are in minority groups, particularly Blacks and Latinos that have been routinely just kind of ceded to the Democratic Party. We’ve seen this over the past few national elections where that is starting to break down in a way that maybe 50 or 60 years ago, the Catholic vote started breaking down or the union vote started breaking down. I think that is arguably the most important shift that is coming. But in these midterms, what we’re going to see is a reversion to older people and wealthier people coming out in large numbers to vote, I don’t think the youth vote is going to be particularly strong or particularly impactful.

What’s the No. 1 misconception about polling?

Judy: Polling is not predictive. It’s a snapshot in time. If you’re polling a race that shows a candidate up by 7 or 8 points, that’s good for that candidate but it does not precede a 7- or 8-point win in November. It’s a snapshot of how the electorate feels at a certain time. One of my friends, a good Democratic pollster Mark Mellman, says that we’re not very good at predicting the future; we’re pretty good at predicting the present and good at predicting the past. I always warn people—the close races are harder to poll. Mathematically, the margin of error in a race that’s 48-48 is higher than in a race that’s 55-40. The closer the race gets, the harder it is to get right. That’s not necessarily a misconception, but it’s more of a warning to folks—as they look at polling, take it with a grain of salt because it’s a snapshot in time.

Keeter: People place way too much faith in polling—they assign to it much greater specificity in its accuracy than it really can sustain, given the fact that it’s based upon a methodology that depends on random sampling.

Cahaly: The misperception is that pollsters know what they’re doing. When average people look at polls and give them any credibility, without knowing a little bit about which poll and who did the poll, that’s a mistake.

Polling is an industry that has not adjusted to where modern people live because they’re still using a lot of old techniques and old methods and, frankly, a lot of old science to do it. That’s why the results are problematic. There is a significant amount of the vote that is going to be very hard to poll. It was one thing when they broke out dirty Walmart shoppers in 2016. In 2020, people were getting canceled, and people were getting called God-knows-what-kind-of-names just for expressing conservative opinions that are out of mainstream media acceptance. So, they chose not to participate in polls. Voters who didn’t want to participate in 2020, [were turned] into submerged voters in 2022. They’re not talking to anybody and not putting signs in the yard. They’re not putting stickers on the car, not posting on social media, and not answering polls—because they don’t want to be labeled.

I believe that there’s going to be a Republican turnout in most states that is higher than anyone is going to predict, including us.

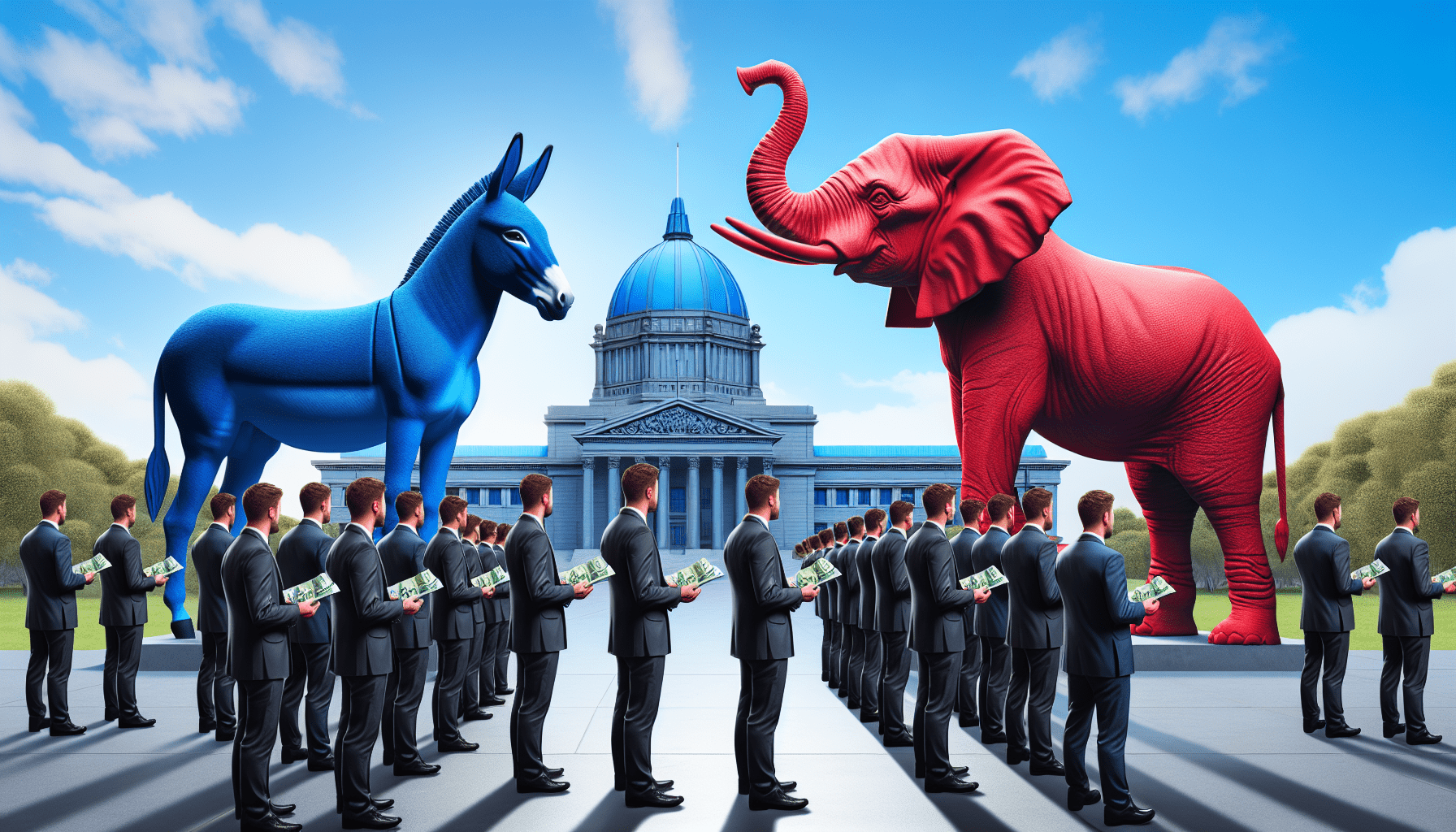

Are midterms determined by the “base”of each party?

Gillespie: President Joe Biden has been going on the attack lately to make the midterms into a national election. Weirdly, in many ways, it’s a referendum on Donald Trump, who’s been out of office and who has very low odds of becoming the Republican candidate in 2024. It’s an understandable strategy, but I don’t think it’s going to work and it’s not going to overpower Biden’s performance so far. He has delivered many of his campaigns promises to spend a boatload of money, but that is not particularly popular. He’s below 50% in terms of approval ratings and, historically, when a first-term president goes into the midterms, and when his party goes into the midterms, they’re losing three dozen seats or more. There’s every reason to believe the Democrats will get wiped out in the House. They may hold onto the Senate. Even Mitch McConnell has commented on the low quality of Republican Senate candidates. It’s just the Republican Party’s penchant, both in presidential races as well as elsewhere, for running candidates who have no political experience, or even any experience in administrative positions. It’s kind of staggering. I think that will come back to bite them in the ass.

Judy: If you cannot turn out your base in the midterms, you have no chance. This cycle with the Senate races, there will be a chunk of swing voters. If you look at what college-educated suburban, ex-urban white voters have done over the last three, or four election cycles, those voters still matter, and there are a lot of them that are still in play. Then again, the Hispanic community is going to be in play in a lot of races, so you can’t just count on turning your base out.