The Shape of Things to Come

The journey of a noted designer-architect shows what may lie ahead for all of us

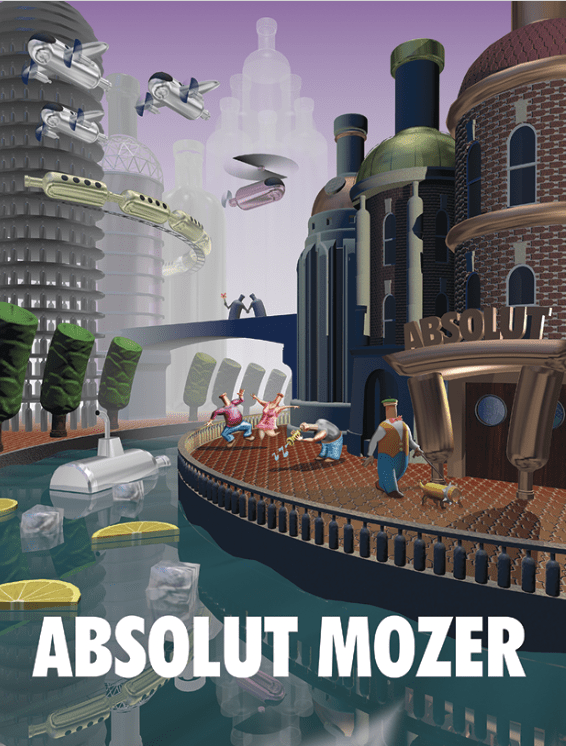

CHICAGO-BASED JORDAN MOZER + ASSOCIATES LTD. BEGAN OFFERING AN UNUSUALLY BROAD RANGE OF INTEGRATED SERVICES IN 1984.

With acclaimed designer and architect Jordan Mozer at the helm, the firm creates buildings and everything that goes into them.

So, it’s not just the often curvilinear exterior walls. It’s also the tables, chairs, sofas, rugs and artwork—most of them seemingly arising from a mind-bending free-form dream.

Then Mozer and his company make the dream real by managing construction and manufacturing.

Beyond Chicago

In his earlier days, Mozer converted lofts into offices, stores and residences. He worked on multi-family residential projects until that market went soft in the recession of 1989, prompting him to concentrate on designing spaces for businesses.

But not just any businesses. One client was Rich Melman, whose Chicago-based Lettuce Entertain You restaurants were among the first to offer upscale casual dining—great food in informal settings.

Melman’s restaurant chains had taken Chicago by storm, partly because each bore its own unique, whimsical, theatrical theme.

Each required a look that embodied its persona.

But Mozer’s work wasn’t limited to a single restaurant operator, or even a single continent. His designs for restauranteurs soon began appearing in Germany and Japan.

Then there were the boutique hotels. He worked with Bill Kimpton, an early proponent of that hospitality niche, and later joined forces with Claus Sendlinger, Christoph Strenger and Bill Marriott.

In Las Vegas, Mozer collaborated with Steve Wynn on Bellagio, Bobby Baldwin on Beau Rivage and Treasure Island, and Sheldon Adelson on the Venetian.

In the world of entertainment, he designed stage sets for The Rolling Stones and worked with Universal Studios and Disney.

He plotted with movie producer and director George Lucas to convert shopping malls into entertainment destinations, a plan derailed by recession.

Telling a story

With all of Mozer’s projects, he endeavors to breathe life into a theme. He calls it turning a narrative into a business plan.

In other words, he says a building and its contents should tell the story of a family, neighborhood or business while giving form to aspirations.

Examples include a Cheesecake Factory in Chicago where the international cuisine suggested a psychedelic Alice in Wonderland look. The curves in the facade of a Minnesota restaurant reflect the rolling prairie that surrounds it.

In another example, the finishes and decor of The East Hotel in Hamburg, Germany, pay homage to the building’s origin as a foundry. But the design also reflects the establishment’s Asian cuisine through design that invokes the wonder of a Westerner’s first visit to Asia.

In a world that rushes to throw up too many modernist structures—destroying the soul of cities in the process—Mozer strives for idiosyncrasy that he says brings meaning to everyday life.

new urbanism.

Design thinking

Mozer came up with an approach to architecture that he now calls “design thinking.” But he began practicing the discipline before he thought to give it a name.

Design thinking begins with defining goals and documenting existing conditions. It proceeds to preparing alternative designs based upon those goals. Along the way, it makes allowance for limitations that can include budget, schedule, law, functionality and marketing. It continues with testing and refining the designs and concludes with execution and analysis.

Mozer uses design-thinking as a catalyst for innovation. It helps set goals based on theories. It can encourage playfulness and engineering focused on culture.

Besides preparing new projects for the future, design thinking can help Mozer reimagine stale older buildings and repurpose them for the future.

“Business operators become very accomplished at managing their business but remain linear as the world around them changes,” he observes. “Design thinking can help break existing patterns to create new solutions.”

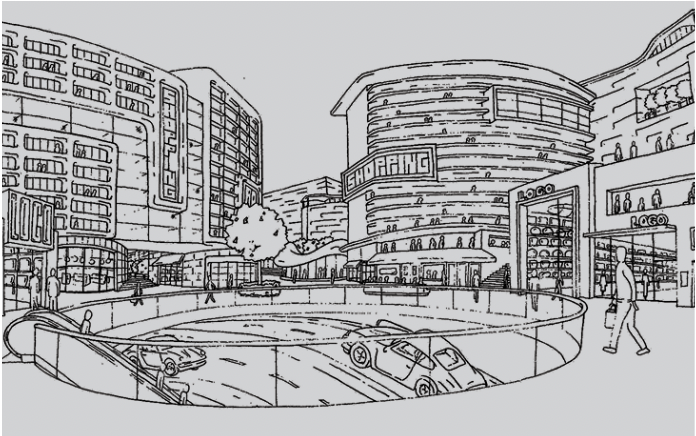

It can help transform the entire urban landscape. “We have applied design thinking methods to creating a new city concept, converting defunct shopping centers, rethinking outdated department store and grocery store models,” Mozer says.

The new urbanism

Much of Mozer’s work centers on the new urbanism, an approach to living that would return city centers to a human scale that’s been lost with the rise of the automobile. It calls for walkable cities with homes, businesses and public spaces in proximity.

visit to Asia.

The new urbanism began attracting adherents in the early ’80s, so it’s not really that new. But it continues to hold promise in the quest to create a sense of place instead of a series of buildings created as “machines” serving limited functions.

Often, creating a future predicated on the new urbanism requires finding a new role for a building that no longer serves its original purpose. Offices are reinvented as play labs, department stores are transformed into hotels, factories become restaurants, malls become entertainment destinations.

Post-pandemic

COVID-19 is forever altering the way people live, and their buildings and furnishings reflect that. For Mozer, the changes don’t come as a surprise.

“I’ve been re-reading [F. Scott] Fitzgerald’s portraits of the roaring ’20s—The Great Gatsby and Babylon Revisited—which describe a cultural revolution in response to the Spanish flu pandemic 100 years ago,” he says. “It seems we have already begun a contemporary cultural shift.”

He provides the example of COVID-induced changes in boutique hotel design. Before the pandemic, hoteliers had begun combining lobbies with upscale destination restaurants that attract diners who aren’t staying the night. The idea was to give travelers an authentic local experience as they mingled with natives over a meal prepared by a noted chef. The trend de-emphasized the hotel’s guest rooms.

But COVID will bring the focus back to the hotel rooms, Mozer says. Quarantines, lockdowns and social distancing have made people leery of crowds, and that trepidation will linger after the pandemic eases. Hence, they’ll spend more time in their rooms instead of venturing into the hotel’s public spaces. They’ll want rooms with more space for room-service meals and in-room exercise equipment. Guests will appreciate the option of reaching their rooms without passing through lobbies.

In another example of the plague altering lifestyles, the shift to online shopping is becoming even bigger and more ingrained, Mozer notes. Changes in store design seem certain to follow, including an acceleration of the fairly recent trend for supermarket designers to group food into areas that resemble small, European-style storefront shops.

Meanwhile, supply-chain disruptions are pushing more businesses to source materials locally, a trend already underway for some time among restaurants. Mozer has availed himself of local manufacturers for years and welcomes others to the practice because he believes it’s environmentally and socially sustainable.

For him, the change the pandemic is bringing is reflected in a quote from writer William Gibson, who puts it this way: “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed.”

Finding the Path

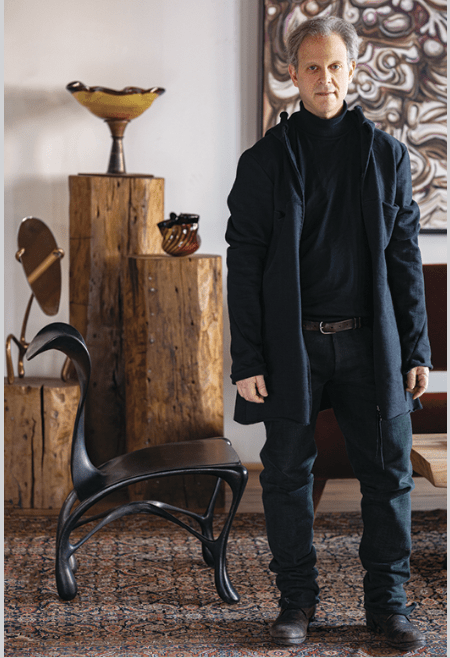

After graduating early from high school, Chicago native Jordan Mozer stood at a metaphorical crossroads.

He could become a doctor like his late father—or he could mix art and commerce the way his mother did in advertising and retailing.

He also thought about a career in architecture and design but felt alienated from what he viewed as the cold and sterile contemporary buildings that surrounded him.

So, he studied painting and sculpture for a couple of semesters at the Art Institute of Chicago. After that he transferred to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he took classes in writing and pre-med while working for two years in a psychiatric ward. Summers, he split his time between carpentry and art class.

Finally, he juxtaposed two profound experiences and brought his future into focus.

Mozer had the first experience when his class was touring the exhibits at the Art Institute. His professor paused in front of a Van Gogh and noted that the artist had hurried to finish the painting before the sun went down.

In his haste, Van Gogh put aside his brush and scraped pigment onto the canvas with his palette knife. The patterns slashed onto the surface brought a new dimension to the painting.

“Next time you see a cypress tree, you’ll recall that pattern of strokes and see the tree as Van Gogh did,” Mozer recalls his instructor saying.

The second experience arose from some lines in a play. It happened when Mozer saw Equus during a trip to

New York. One of the characters reminds the protagonist, a hesitant psychiatrist, of his professional obligation to help a disturbed boy see the world as

others do.

It dawned on Mozer that the artist and the psychiatrist were walking the same path in opposite directions. Psychiatrists help people see things normally. Artists helped them see things differently.

He realized he preferred the latter. Thus, he turned away from psychiatry and the practice of medicine to complete his first degree in industrial product design and his second in architecture.