We’re Finding Plenty To Criticize in the Harris and Trump Economic Platforms

Polarization aside, some policy proposals of both the left and the right are wrong

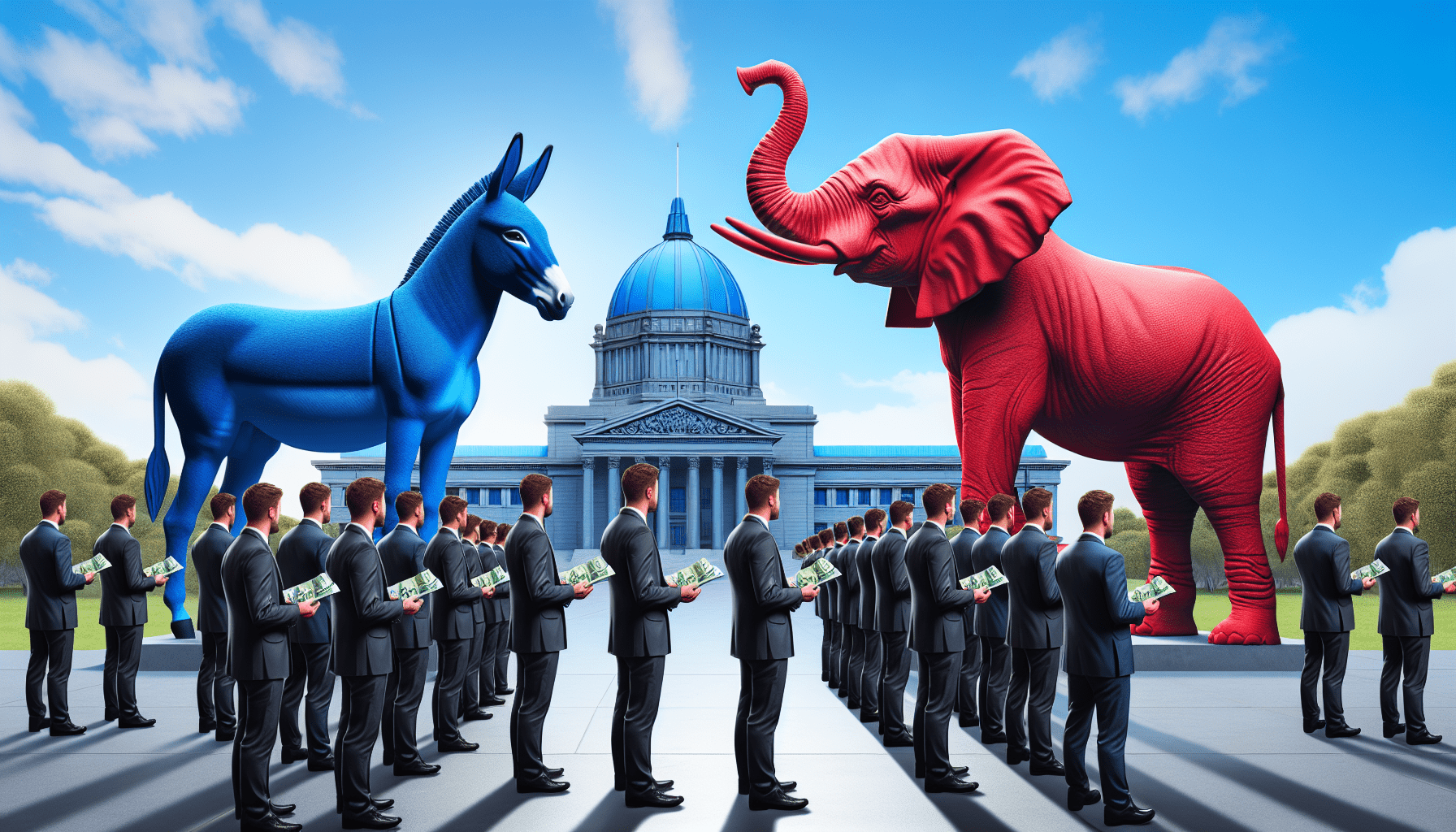

Former President Donald Trump tends to lean right on economic issues, and Vice President Kamala Harris generally hews to the left—no surprises there.

But neither presidential candidate demonstrates a great deal of confidence in free markets, and both are making proposals that leave economists gawking in wide-eyed disbelief.

Examples abound, but let’s focus on two: The Harris position on unrealized capital gains and the Trump stance on tariffs.

Harris on taxing unrealized capital gains

Harris proclaims she’s onboard with President Joe Biden’s plan to tax unrealized capital gains.

Unrealized capital gains occur when the value of an asset increases but you don’t sell it. Say you buy stock for $100 per share and the price increases to $120, but you hold onto it instead of selling. The $20 difference is an unrealized capital gain.

While your net worth has increased by $20, it’s at risk of withering away and could even become a loss unless you sell the equity. It works the same way with real estate and other assets.

The levy on unrealized capital gains, also known as a “wealth tax,” would require households worth more than $100 million to pay an annual minimum tax pegged at 25% of their combined income and unrealized capital gains. Biden proposed it in his 2024 budget.

The goal is to collect revenue from anyone who avoids taxation by living off unsold assets. But how do you calculate any of this? After all, no price has been locked in for assets such as real estate, collectibles and private investments, which makes valuation tricky. Plus, the tax could disincentivize long-term investments.

Indeed, some active investors in equities might even consider this tax proposal a strong rejection of the principle of free markets. But Harris has an opponent whom some would regard as equally skeptical of allowing the markets to go their own way.

Let’s look at the Republican nominee’s thoughts on one of government’s most powerful trade weapons—tariffs.

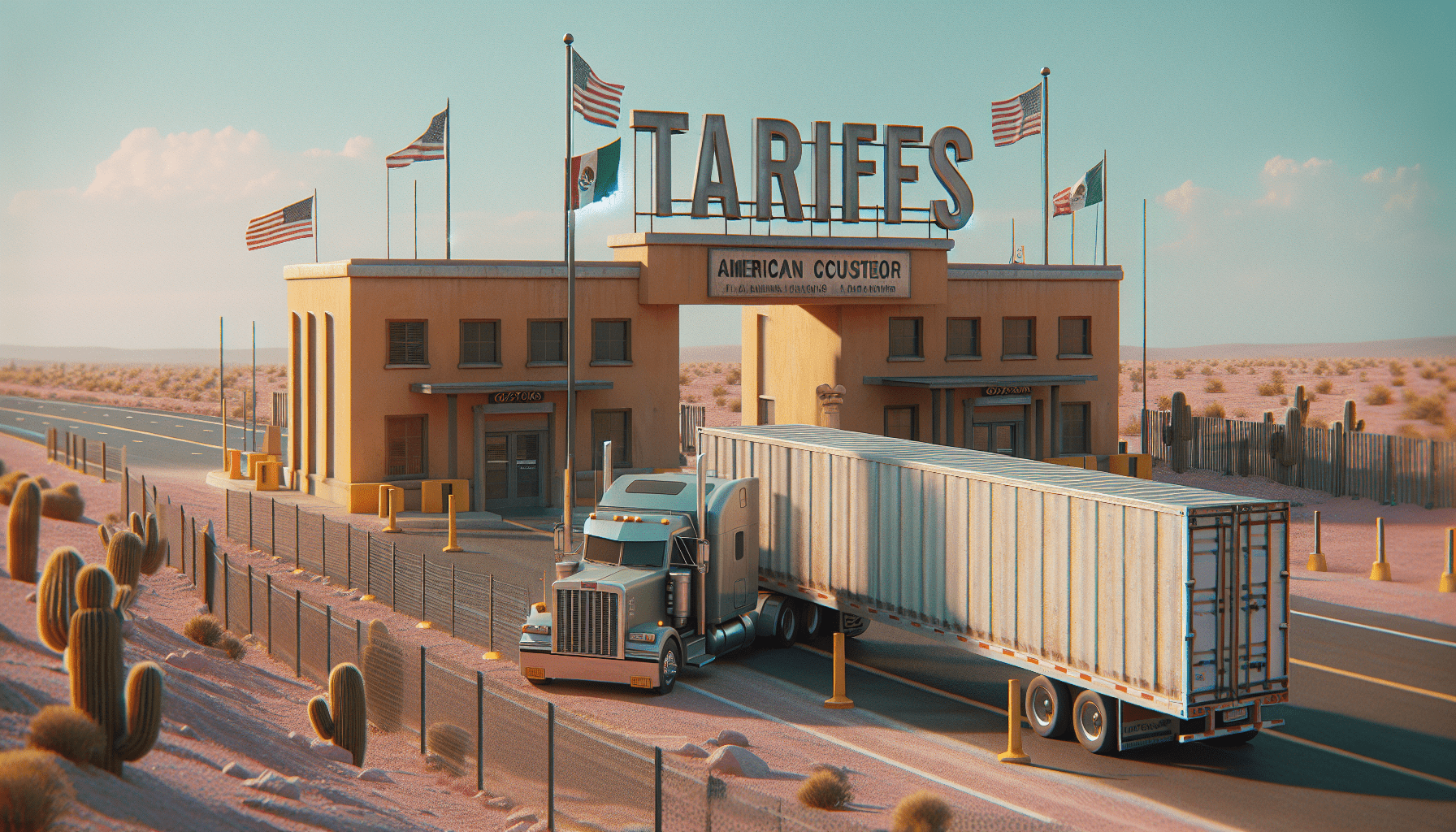

Trump on erecting trade barriers

Import duties, better known as tariffs, are supposed to reduce a nation’s trade deficit by raising the price of merchandise made in other countries. The hope is that this encourages consumers to substitute domestic goods for those made abroad. Or they could simply do without whatever feels too pricey.

But tariffs seldom do much to reduce a trade imbalance, according to numerous sources. The cost of the tariff is passed along to American consumers, simply making them feel poorer.

Meanwhile, American manufacturers pay more for raw materials and intermediate products from abroad, raising their production costs or even causing them to withdraw from the market. That can leave America with less to export, striking another blow to the dream of a tariff-induced improvement in the trade deficit.

Someone should tell Trump about this. He doesn’t seem to have learned the futility of tariffs after being quick to wield them during his term in office.

In January 2018, he imposed tariffs on China—a 30% levy on solar panels and a 50% penalty on washing machines. Two months later, he slapped tariffs on goods from most countries, charging 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum. By summer of that year, he extended tariffs to the European Union and Canada.

If any import-export ledgers were balanced as a result, we missed it at Luckbox.

These days, Trump’s proposals for new tariffs of 10 percent or even up to 20%, are bandied about at rallies and on TV. The tariffs he’s proposing would cost Americans an estimated $300 billion annually, says the Tax Foundation, which describes itself as a nonpartisan educational organization.

Arithmetic tells us that if we divide that figure by the 345.4 million—the number of people in the country— the cost of the tariffs would come to an average of $869.57 for every man, woman and child. That’s $3,478.28 for a family of four. With a median income before taxes for a family that size calculated at $74,580, they’d be paying 4.66% of their annual income to cover the tariffs.

In fairness, however, we’ll note the Biden-Harris administration maintained many of the tariffs Trump imposed. So, a Harris presidency might look much the same. For both camps, tariffs offer a way of trying to shape the world to benefit American workers and American industries.

Trump’s policies have favored the steel and fossil fuel industries, while Biden and Harris have pushed for green energy projects. Those opposing paths share the goal of creating jobs and protecting potentially vulnerable industries and the workers who depend upon them—tasks some would leave to the markets.

Ed McKinley is Luckbox‘s Editor-in-Chief.