Fix the CPI or Bust

A new century dawned a long time ago. When will the Consumer Price Index catch up to the way we actually live?

I have a framed print that I found at a local art fair. (No, it’s not Live, Laugh, Love. I’m not a psychopath.) It’s a picture of a Chihuahua with the caption, “I work hard so my Chihuahua can have a good life.” I don’t often think about inflation and the Consumer Price Index (CPI), but I do think a lot about what it’s going to take to keep my Chihuahua in the lifestyle to which she’s accustomed. I’m sure the same thought runs through the heads of sugar daddies as they log onto seekingsugarbaby.com: What’s it going to take to keep Kandiss in the lifestyle to which she is accustomed?

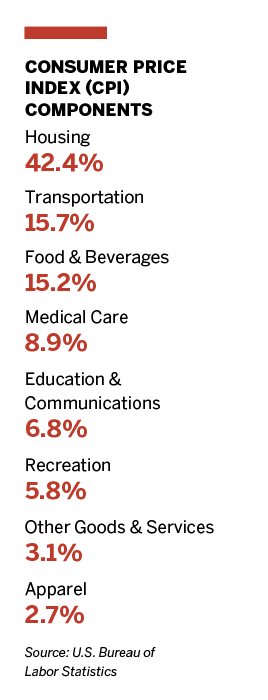

In terms of plum writing assignments, “ramifications on consumer discretionary spending during sustained periods of inflationary pressure” ranks just above “first-person account of a root canal.” But we’re going to make it work. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) produces the CPI, the most widely used measure of inflation in the United States, and by some accounts, it’s the highest it’s been in 30 years. But if you Google “What’s wrong with CPI?” a litany of issues arises. Man, who knew economists could be so ornery? Their calculations vary wildly, and they don’t agree on whether the CPI is overstating or understating inflation.

When it was created, the CPI simply compared the cost of a fixed basket of goods between two time periods. OK, if my little basket of groceries last month cost $100 and then this month cost $125, that’s inflation, baby! But that doesn’t tell the whole story, so now CPI has evolved into a cost of living index. This method “takes into account changes in the quality of goods and substitution. Substitution [is] the change in purchases by consumers in response to price changes,” writes Investopedia.

There’s a lot of nuance to consumer spending. The price of one good may not go up by a measurable amount because people stop buying the most expensive item and instead buy a cheaper one, thus substitutingit. Or, consumers might spend a lot of money on a product or service at the onset, but that product or service is of much higher quality than was previously available so they don’t need to buy it as often.

In an age when everyone knows everything about you because your data is in the cloud, the U.S. economy is still using a rotary phone.

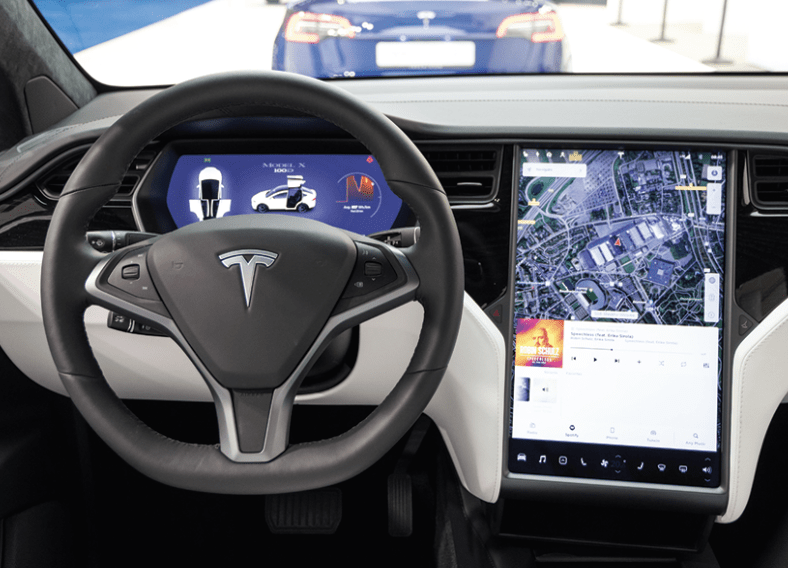

In his book The Inflation Myth, Mark Mobius writes that “it’s hard to define exactly what is meant by the cost of living when new goods are introduced on a daily basis. One example of that would be the automobile. ‘Today’s automobiles are … much improved than in the past … offering all kinds of conveniences that did not exist before.” Last year, I bought a new hybrid SUV. So, some pencil-pushing economist would put the price of my car into a spreadsheet, but other factors, like the 50% monthly reduction in what I pay for gas and the 30% reduction in my insurance premium (it has a lot of safety features) wouldn’t be counted. The result is a CPI that doesn’t actually account for what’s happening. It’s not just that CPI measures only what’s happening in brick-and-mortar stores. Investopedia notes that it fails to consider “the spending habits of those living in rural areas, including farm families.” It also neglects members of the armed forces and leaves out nearly everyone in prisons or mental hospitals. Yes, the CPI covers approximately 93% of the population, but those groups seem too important to ignore.

According to Investopedia, the CPI’s basket of goods is filled with basic food and beverages such as cereal, milk and coffee. “It also includes housing costs, bedroom furniture, apparel, transportation expenses, medical care costs, recreational expenses, toys and the cost of admissions to museums,” the site said. “Education and communication expenses are included in the basket’s contents, and the government also takes note of other, seemingly random items such as tobacco, haircuts and funerals.” But a lot gets left out.

We need a new measure of inflation for a new era of consumers, so I’m pleased to present my own updated version of CPI which I am calling Baseline Observation Of Buying Sprees, or BOOBS. That’s right, check out my BOOBS.

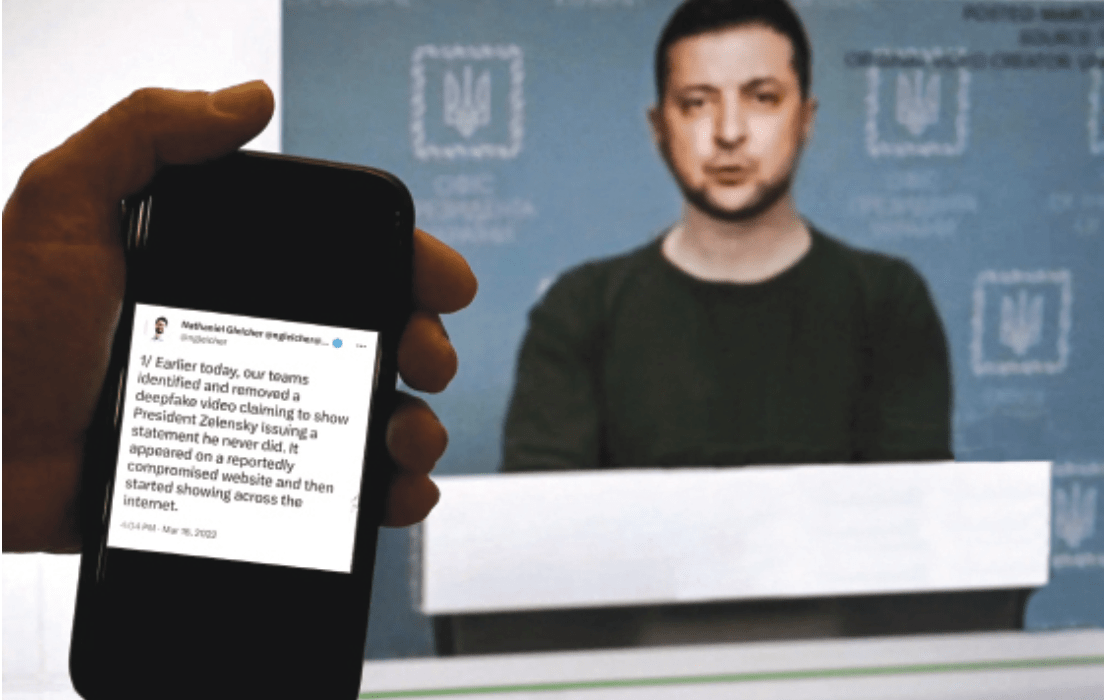

Step 1: Get modern. It’s almost 2022, and you’re telling me that key measures of economic data are based on calling some lady in Peoria on her landline and asking what she spent on Raisin Bran? Hedge funds are flying drones over Apple store parking lots and aggregating the data on Google Maps to see how many people are in line for the latest phone. My banking app magically knows how much I spend each month on a wide array of goods and services. Why can’t we anonymize the data but pull real-time spending info from people’s actual bank accounts? Instagram’s algorithm took two days to figure out I had a thing for bearded dudes wearing flannel before it filled my timeline with hot lumberjacks. Why can’t we do the same with real-time consumer data?

Step 2: Expand your BOOBS. CPI has so many biases and blind spots it just got its own cable news show. Include rural families. Include online shopping because that’s all most of us are capable of. Normalize the data to account for the higher cost of living for single people. I guess economists get laid way more than I do because I couldn’t find anything that states that CPI is adjusted based on marital status. Spoiler alert: Single people spend more money because they can’t spread out the costs. Those boxes of wine, pallets of cat food and sleeves of D batteries aren’t free, Milton.

Step 3: Account for fake BOOBS. Investopedia notes that BLS freely admits that the CPI does not factor in the effects of substitution. When certain goods become significantly more expensive, many consumers find less expensive alternatives. For instance, they might buy the store brand instead of the name brand, or replace premium gasoline with regular. In the words of George Costanza, “cheapness is a sense.” American consumers are super savvy about sniffing out deals. Sleep in a tent to get $50 off a TV? OK! Hoard 15 pallets of paper towels in my garage and be forced to park on the street because I had an awesome coupon? Done! Get thrifty! Get schwifty!

Here are a few categories I would expand as a metric of BOOBS:

• Plants — they’re the new pets

• Pets — they’re the new kids

• Sin — booze, weed, frisky time (how is this not included in our GDP?)

• Online shopping

• Inclusion of rural, military and incarcerated populations—and, oh yeah, single people (that’s a lot of ramen going

unaccounted for)

• The coupon conundrum — Americans rock at sniffing out deals

In an age when everyone knows everything about you because your data is in the cloud, the U.S. economy is still using a rotary phone. The treasury secretary says inflation is nothing to worry about, but my banking app makes the saddest sound when I open it. There’s a disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street, and the way we’re currently measuring inflation isn’t working. Can my BOOBS save the economy? Maybe. But my new metrics are real, and they’re spectacular.

Vonetta Logan, a writer and comedian, appears daily on the tastytrade network and hosts the Connect the Dots podcast. @vonettalogan