Options Trading: An Antidote for Division

Smart options traders know that life—and markets—aren’t zero-sum games

Trading can bring the country back together. That’s right. Trading. Anyone can see all the anger out there. Over politics, culture, religion. Most “leaders” seem powerless to overcome it, and some even seem to revel in it. But to understand how trading can ease this nation’s—and the world’s—raw nerves, consider a big reason for how the country got here: differing interpretations of news.

When two people look at the same event or data and come to completely different conclusions, they’re setting up for conflict. When President Donald Trump makes a decision, some see it as an act of injustice, or even a crime. Others view it as fulfilling the duty of the office. The formula’s simple. One decision + two vastly different interpretations = anger.

In a framework of winning and losing, only one side wins. That means the other interpretation loses, and nobody wants that fate. The theory of loss aversion says that the pain of losing is greater than the joy of winning. So, Americans yell, scream and type with all caps to avoid losing, oblivious to the idea that both sides could be right, or wrong.

This is the source of the battle between fake and real news, even augmented versus experienced reality. When the emotional stakes are high, it’s easy for one side to create a fictitious story just to score points on the other side, and why some people label any story they don’t like as “fake.” But here’s a truth about trading that can set everyone free: the news doesn’t matter. In trading, two people can look at a stock or index, read the same news, look at the same chart, analyze the same fundamental data, and one might see a bullish trade while the other sees a bearish trade. But both can be profitable. What?

Do the math

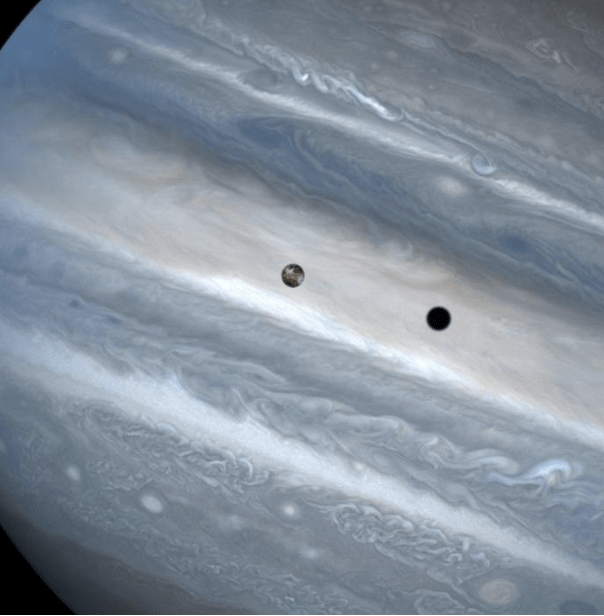

Sure, in the grand scheme of trading, it’s a zero-sum game, particularly in the new world of zero-commissions. If one investor buys 100 shares of Twitter (TWTR) at $30 and another shorts those 100 shares of TWTR at $30, and TWTR does anything but sit at $30, neither investor will gain nor lose money. If it goes up to $31, the first investor wins, and the second one loses. If it goes down to $29, the first investor loses, and the second wins. That, indeed, is a zero-sum, 50-50 bet.

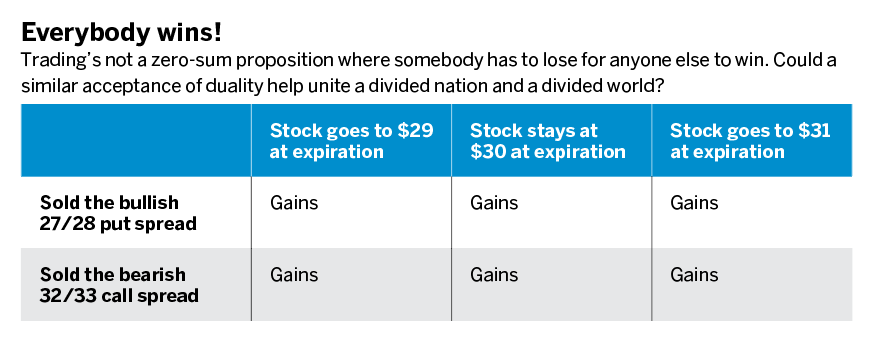

But imagine if the first investor sold the 27/28 put spread (a bullish trade) and took in .30 credit instead of buying stock, and the second investor sold the 32/33 call spread (a bearish trade) and took in .30 credit instead of shorting stock. If Twitter is $31 at the options’ expiration, the first investor makes $30 and the second makes $30. If Twitter is $29 at expiration, the first investor makes $30 and the second makes $30. Hmm, only one had the correct directional opinion of Twitter, but both make money. The first investor’s bullish assumption would be correct if Twitter rose to $31, but the second investor’s bearish assumption would be correct if Twitter dropped to $29. But with TWTR at either $31 or $29 at the options’ expiration, both the short 27/28 put spread and the short 32/33 call spread expire worthless, and both investors keep that $30 credit. The first investor’s happy. The second’s happy, too. Magic? No, just probabilities.

Both the short put vertical and the short call vertical have theoretical 70% probabilities of making a profit at expiration. Compared to a 50% probability of making money on long or short stock, that may not seem much higher. In terms of trading success over time, though, that increased probability of profit can mean everything. Plus, those probabilities aren’t based on any single opinion, but rather the cumulative buying and selling of hundreds of thousands of market participants.

The right way

Using smart options strategies that have high probabilities of making money, investors are breaking free from the binary thinking of winner versus loser. That way of thinking stinks for trading and is making the country angry. Of course, any trade can lose money, even if it has a high probability of profit. But investors can quantify why it lost money—the stock went up higher or down lower than the market anticipated, or it didn’t move enough before the option expired, or volatility went up or down.

The investor isn’t the reason the trade lost money. It lost money because of the random nature of markets that give even the most sound trading strategies an occasional loser. In fact, trading can provide an entirely different perspective on the events of the day. Take trading seriously and treat the news as a hobby, without the bloodthirsty need to be “right.” It will pad the bank account and lower the blood pressure.

Tom Preston, Luckbox features editor, is the purveyor of all things probability-based and the poster boy for a standard normal deviate.