ZIRP-NIRP Primer: Will Fed Go From Zero to Negative Rates?

On Dec. 16, 2008, with the world economy overwhelmed by the Global Financial Crisis, then head of the U.S. Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke announced that the American central bank was lowering its benchmark target interest rate to nearly zero.

At that point, U.S. stock indices like the S&P 500 were already down roughly 40% from the highs touched 18 months earlier in the summer of 2007.

The announcement by Bernanke marked the first time in American history that the Fed had dropped interest rates to such a minuscule level, and therefore represented the country’s first foray into Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP).

ZIRP, in short, is a macroeconomic concept that describes conditions characterized by extremely low nominal interest rates. ZIRP generally means that a central bank has a set a target of zero, or close to zero, for its short-term benchmark.

The primary goal of ZIRP is the same as any period in which a central bank is dropping prevailing interest rates: to catalyze economic expansion as well as to boost inflation by disincentivizing the hoarding of cash, and instead incentivizing lending, spending and investment.

ZIRP represents an important milestone because it theoretically means rates can’t be dropped further, as the lower bound (zero) has been reached. Because of this, the arrival of ZIRP is perceived to be a time in which central bankers have “run out of bullets,” because their primary tool for controlling monetary policy has essentially been neutralized.

In modern times, that isn’t entirely true, because ZIRP in several instances has transformed into NIRP (Negative Interest Rate Policy), which will be covered in more detail below.

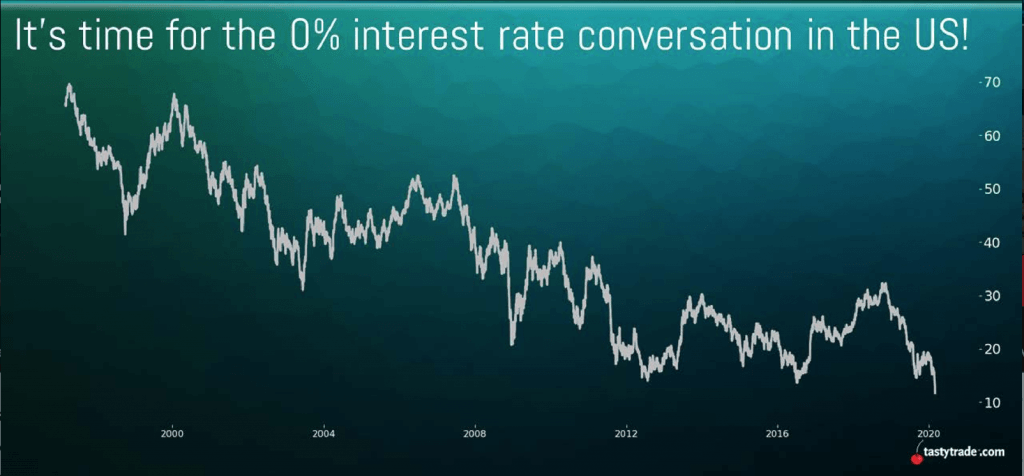

The United States adopted ZIRP in 2008 and held rates near zero until 2015 (approximately 7 years) before the American central bank finally said the economy was healthy enough to warrant marginally higher rates.

The Fed consequently was able to gradually raise short-term interest rates as high as 2.5% percent (from zero) during the years 2015-2019, as shown below:

Fast-forwarding to the present, all that work on raising the interest rate environment back toward “normal” levels has been wiped away in the span of roughly eight months—and the bulk of it in the last two weeks.

As of March 15, 2020, ZIRP officially returned to U.S. soil, primarily as a defensive tactic aimed at helping to insulate the American economy from negative shocks related to the ongoing global coronavirus crisis. This time around, major stock indices like the S&P 500 are down roughly 30% from recent highs.

In terms of providing broader context, it should be noted that zero interest rate policies have been experimented with in other countries before the U.S. adopted this approach in 2008.

The best-known example involves the country of Japan, which was fighting against so-called “stagflation” in the 1990s. Stagflation is typically characterized by high unemployment, stagnant demand in the economy, as well as rising inflation, which is a trifecta of negative headwinds.

In order to try to catalyze growth in the economy, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) adopted ZIRP by dropping rates to extremely low levels in the late 1990s. At this time, the move was viewed as a rather unconventional, if not innovative, approach to managing an economy. Interestingly, the BOJ doubled down by also introducing the concept of quantitative easing (QE) at this time, as well.

QE essentially entails large-scale asset purchases, particularly of government bonds, which has the effect of boosting the price of those assets and increasing overall money supply.

Looking back on this approach roughly 21 years later, one could say at best that the results of the BOJ approach have been mixed. Modern analysis of the approach suggests that the BOJ was able to stave off deflation and do some catalyzing of the Japanese economy.

On the other hand, a review of the last two decades also illustrates that it has been nearly impossible for Japan to wean its way off from ZIRP. While trying to raise interest rates to normal levels at the turn of the most recent century, the dot-com bubble materialized and forced the BOJ to take rates back to zero.

Then, when a campaign to normalize rates resurfaced in Japan around 2006, it wasn’t long after that the Global Financial Crisis foiled that idea once again. Due to the severity of the 2008-2009 Global Recession, the BOJ was also effectively forced to move from ZIRP to NIRP (Negative Interest Rate Policy).

NIRP is exactly as it sounds, and occurs when central banks set target interest rates below 0%.

Such an environment means that instead of earning a rate of return on savings, depositors are charged a fee for parking their money in cash. The purpose is the same as lowering interest rates to zero, just more extreme – to disincentive the hoarding of cash, and instead incentivize lending, spending, and investment.

The severity of the financial crisis caused other countries like Denmark and Switzerland to adopt NIRP, as well as Sweden. The Swedish central bank, called the Riksbank (the oldest in the world), dropped their overnight deposit rate below zero in 2009, and basically kept it there until January of 2020.

Intriguingly, it was just this year that the Riksbank abandoned NIRP, purportedly because the Swedish economy had reached its intended inflation target – albeit much later than expected.

However, with the arrival of the coronavirus crisis, it’s doubtful Swedish rates will remain in positive territory for long. This example helps reinforce just how tricky it can be for a country to emerge from NIRP once it has been initiated—the so-called ZIRP-NIRP “trap.”

The examples of Japan and Sweden naturally make one wonder if the United States might ultimately see its rates drop from near-zero into negative territory, as well.

Recent comments made by the same central banker that was so instrumental in bringing NIRP to the United States in the first place seem to indicate that ZIRP in the U.S. at some point in the future is a real possibility.

The former Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, delivered a somewhat intriguing keynote address at an economic forum held in early January of 2020. During the speech, he seemed to suggest that negative rates shouldn’t be ruled out by the US Federal Reserve going forward.

Specifically, Bernanke said, “The Fed should also consider maintaining constructive ambiguity about the future use of negative short-term rates, both because situations could arise in which negative short-term rates would provide useful policy space; and because entirely ruling out negative short rates, by creating an effective floor for long-term rates as well, could limit the Fed’s future ability to reduce longer-term rates by QE or other means.”

Whether Bernanke was soft-balling the concept into the American consciousness in conjunction with his former colleagues, or merely musing on potential developments in the distant future is anyone’s guess.

What can’t be ignored is the fact that previous experiments with ZIRP and NIRP have yielded mixed results, and more importantly have illustrated that such regimes are difficult to shed once initiated. An economy reliant on low-cost debt apparently can’t change its nature overnight.

Before going negative on rates, leading economic thinkers in the United States therefore might first look in the mirror and ask themselves, “If super-low interest rate regimes adopted in the wake of the Financial Crisis didn’t achieve their intended goal(s), is it rational to believe a NIRP approach would be any different?”

Stated more directly, one has to wonder whether the answer to every future economic crisis is more cheap debt. Or whether strings should be attached to the new debt that incentivize real investment in the underlying economy, as opposed to funding more stock buybacks.

With the world currently reeling as a result of the spreading coronavirus, that question may have to be tabled until the next recovery.

For more information about super-low interest rate environments and how they can affect the financial markets, readers may want to review a recent episode of Futures Measures on the tastytrade network when scheduling allows.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.