The Art of the Guarantee

THE TWO BIG AUCTION HOUSES ARE EARNING RECORD PROFITS AS THE INCREASINGLY WEALTHY TOP 1% SPEND MORE ON ART. HERE’S WHAT INVESTORS NEED TO KNOW AS ONE OF THE SCENE’S PROMINENT PLAYERS CONTEMPLATES ITS RETURN TOTHE PUBLIC MARKETS.

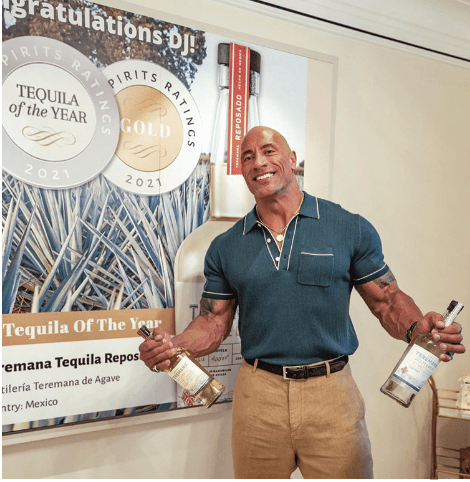

In June 2019, French-Israeli entrepreneur and art collector Patrick Drahi took the Sotheby’s fine art auction house private in a deal worth roughly $3.7 billion.

Drahi arranged to pay $57 per share, a premium of 61% over Sotheby’s closing price on June 14, 2019. About 91% of shareholders approved the offer. Domenico De Sole, then chairman of Sotheby’s, called the offer a “significant premium to market” for shareholders.

But some of those former owners may now be looking back and wondering if it was such a good deal after all. Are they right to dream of a do-over and wish they had held out for an even higher price?

Yes. Based on recent developments in the art and auction world, it appears that Drahi might have made the deal of a lifetime.

In 2021, Sotheby’s chalked up the healthiest numbers in its 277-year history, thanks to an explosion in global wealth, innovation in digital artwork, a keen interest among millennials in acquiring art and a profitable sales strategy known as a “guarantee.”

So with no auction houses currently trading publicly in the United States, an outcry could arise for one of the two big ones to return to the public markets. That could offer investors a way to take part in investment trends now limited to members of the top 1%.

A 13-figure asset class

Art itself is considered an alternative asset class, marked by illiquidity, exclusivity and opaque business practices.

But the size of its market might surprise investors new to the sector. It surpassed $1.7 trillion in value in mid-2021, according to the Chartered Alternative Investment Association (CAIA).

But the association notes that for years a lack of quantitative research has made it difficult to assign a precise number to the art market’s size.

However, recent technological advances and newfound interest in alternative investments have helped create a more accurate valuation profile and fueled increased securitization of artwork.

To put that $1.7 trillion figure into perspective, compare it with other alternative markets.

CAIA said in 2021 that artwork comprises about $60 billion in annual transaction volume and represents about 75% of the total collectibles market, which also includes jewelry, watches, cars, wine and sports memorabilia.

Art as an asset class is more than double the size of the $800 billion market for private debt and half the size of the $3.4 trillion private equity market, the July 2021 CAIA report said. Art has more value than the world’s $1.6 trillion in private real assets.

And the art market stands to get even bigger.

A stronger duopoly

It’s hard to overstate the strength of the art auction world in 2021.

Sales for the three biggest players—Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips—reached $6.5 billion in 2021, surpassing the record set in 2018, said art market research firm ArtTactic.

They were also up roughly 74% year-over-year from COVID-plagued 2020 and up 21.7% in 2019 when Sotheby’s went private, the researchers said.

Art was responsible for a large part of the houses’ success, but they also sold plenty of other luxury products ranging from bracelets to diamond bags. In a world where the wealth divide continues to widen, it seems only appropriate that Marie Antoinette’s bracelets sold at an auction for $8 million.

In 2021, the three largest auction houses reached a record $15.5 billion in combined sales of art and other merchandise, reports said.

Sotheby’s set a company record of $7.3 billion, which didn’t include the proceeds from the company’s final 20 auctions of the year. Christie’s placed second on the list at $7.1 billion in sales.

Do the math, and it becomes obvious that the auction industry operates as a duopoly.

No fine art auction houses are traded publicly in the United States. But SOTHEBY’S COULD GO PUBLIC THIS YEAR.

Phillips, the third-largest auction house, reported $1.2 billion in sales, yet its market share declined from 8.7% in 2020 to 7.6% last year. Meanwhile, Christie’s market share increased from 40.9% in 2020 to 42.6% last year, ArtTactic said.

Because all three companies are private, no would-be stock market investors could tap into those strong sales figures or into the underlying trends that have helped auction houses ascend to new heights.

NFTs’ growth spurt

Global wealth set new records in 2021, accelerated by central bank intervention. That powered a surge in asset prices around the world, with the spoils largely ending up in the holdings of the top 1%.

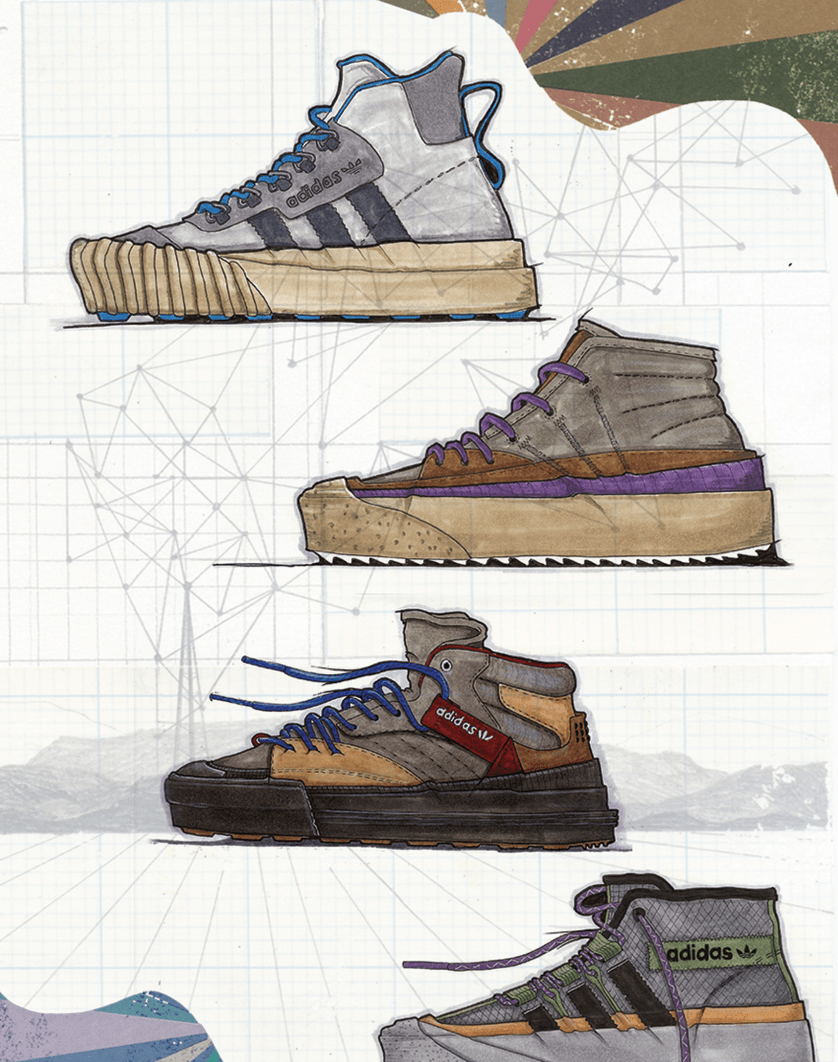

They had more to spend on everything from artwork and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to watches and collectible sneakers. First-time buyers that included newly minted millionaires and billionaires flocked to auction houses or sat down in front of screens for online auctions.

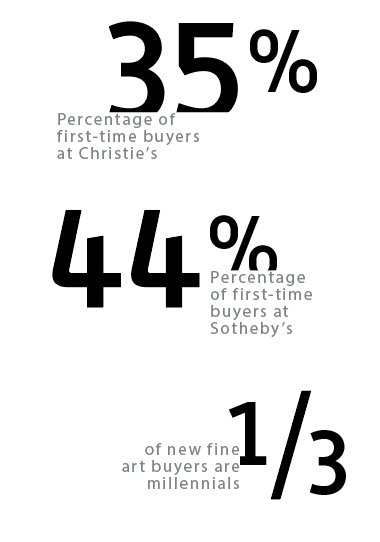

Christie’s reported that 35% of recent buyers were new to the company’s auction house. Sotheby’s said new clients accounted for 44% of the revenue from its auctions. One-third of the new buyers, according to records, were millennials, ages 26 to 41.

A younger audience helped increase demand for contemporary works by emerging artists. Creations by artists under 45 became the fastest-growing category of art at auctions last year, ArtTactic said. Stars included Adrian Ghenie, Matthew Wong and Beeple.

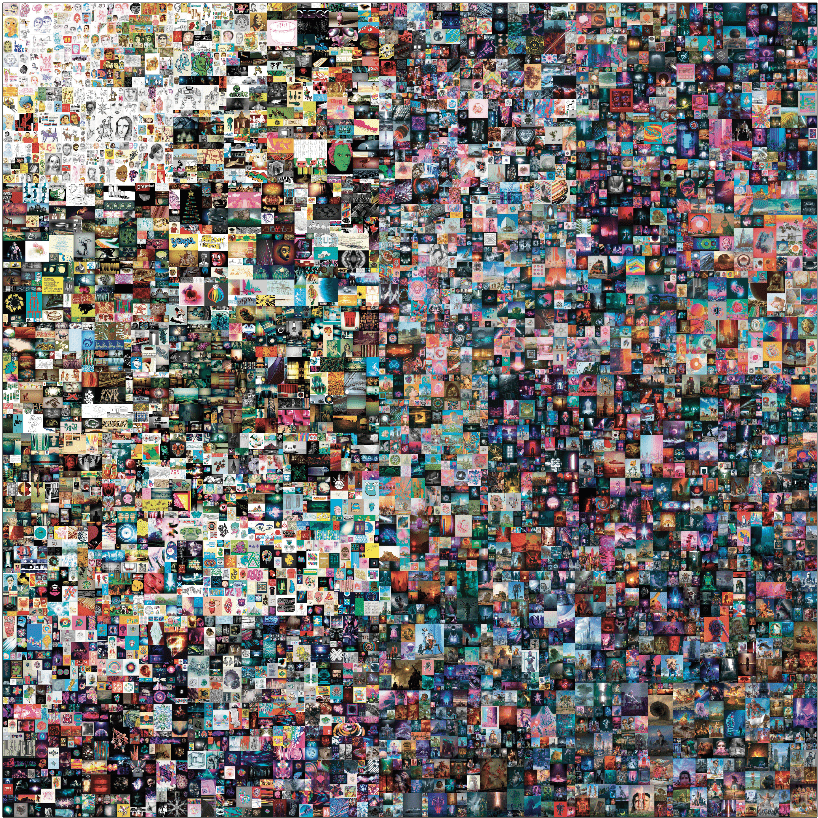

Meanwhile, cryptocurrencies were recording highs and became the coin of the realm for buying NFT art. Christie’s sold $150 million in NFTs last year, notably including the $69 million sale of Beeple’s Everydays. It bested the $100 million sold through Sotheby’s NFT marketplace “Metaverse.”

The auction houses also experienced strong “private sales.” Through that process, buyers purchase goods directly from the auction house without an auction. Christie’s private sales reached $1.7 billion, while Sotheby’s recorded private sales of about $1.3 billion.

Private sales are related to one of the most important drivers of auction houses’ success: the commitment to a largely misunderstood practice known as “guarantees” that ensure a floor for the price of a work that’s heading into a live auction.

Evolution of the guarantee

It might seem that a new piece of art or a French aristocrat’s jewelry collection might go up for auction and just sit there on the stage without attracting a single bid. Attendees might find the reserve price too high.

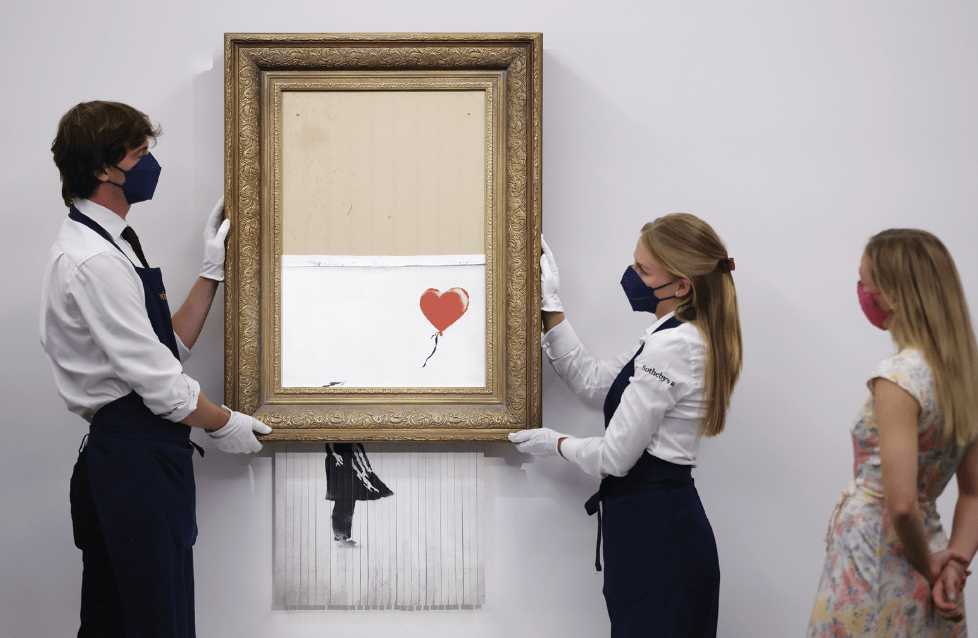

But the auction houses use a little-known hedging strategy that ensures a sale. The “guarantee” means that before the auction takes place, the auction house has already found a buyer willing to fork over a certain amount of cash for the merchandise. Think of it as insurance for the art house and the seller. It’s akin to a call option on art.

Guarantees, introduced in 1971 at Sotheby’s, started as a minimum bid in an auction of 47 Kandinskys and other works from the Guggenheim Museum, according to The Art Newspaper. Similar deals followed over the next two years on Ritter and Scull

art collections.

That was in the days before houses instituted a buyer’s premium. Instead, the art house risked its own capital and bet on a higher commission from the seller or bigger profits over the guaranteed purchase level. Those guarantees disappeared for a while and re-emerged during the 1980s as Japan’s burgeoning wealth created a new set of buyers, The Art Newspaper said.

Guarantees have come and gone over the years with the ebb and flow of buyer interest and broader economic conditions, according to a report written last year by Nathan Krasnick, an investment operations associate at Masterworks.io.

Krasnick also noted that guarantees have returned in grand style. In fact, in today’s auctions, nearly everything is pre-sold.

Megan Fox Kelly, president of the Association of Professional Art Advisors, noted that “it’s just a question if somebody steps in with a higher offer.”

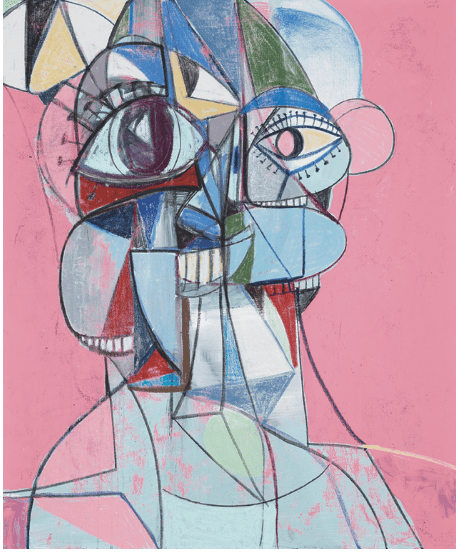

Kelly offered the example of a collector who wants $100 million for a Picasso. Christie’s may be willing to guarantee that the seller receives that price regardless of how or where the piece sells.

The auction house would then attempt to sell the work for more than $100 million and keep the difference. It could sign a contract with a speculator who guarantees the purchase and splits the profits with the auction house.

Suppose the two parties agree to a 50-50 split, and the painting sells for $110 million at auction. Each gets $5 million. In effect, the seller and auction house held a private auction before the public auction.

Guarantees provide auction houses a lower-risk way to ensure a profitable sale for expensive artwork while capitalizing on the frenzy in a market marked by exclusivity. It’s a brilliant business model, even if it frustrates new entrants to the market who want to win auctions.

Going public?

No auction houses trade publicly in the United States, but that could change.

Sotheby’s could return to the market with a higher valuation as soon as this year, according to Bloomberg News. In fact, Drahi is already exploring a potential initial public offering, reports said.

If Sotheby’s does go public, investors who sold their stake for that 61% premium might be paying even more to own a piece of the company again.

Chalk it up to the new mania for owning fine art and the resulting boom in auction houses—plus a momentous deal by a prescient entrepreneur.

The Perfect Trade

The two largest fine art auction houses employ a mechanism called a “guarantee” that ensures a seller receives the desired price.

Notably, the guarantees also happen to provide investors with a foolproof way of turning a profit.

“It’s like a perfect options trade that doesn’t exist,” noted Luckbox Technical Editor James Blakeway.

Imagine buying 100 shares of stock at $9 each for a total of $900 but owning a $10 strike put option for free. That means you may choose to sell the stock for $10, but you don’t have to.

It’s guaranteed that the owner can sell the stock at $10 per share regardless of subsequent price action. “No matter what, you have a ‘guaranteed’ $100 profit ($1 x 100 shares),” Blakeway said.

If demand is strong, sellers don’t have to part with their shares for $10 each. Instead, they can sell at the going rate in the market, whether it’s $12, $13 or even more.

The only caveat is that the seller splits the profits with the guarantor that “sold” the put option. Essentially, it’s a risk-free, no-lose trade.