Don’t Touch That Dial

This year marks the 100th birthday of commercial radio. On Nov. 2, 1920, the first commercial station began broadcasting in Pittsburgh, and the next 20 years became known as the Golden Age of Radio. Popular culture would never be the same. As the years passed, some of the biggest hit songs, in a true “meta” fashion, were about radio. Think of Queen’s Radio Ga-Ga, The Buggles’ Video Killed the Radio Star and Elvis Costello’s Radio, Radio.

By 1929, nearly 40 million American homes had radios, and one of the hottest stocks of the Roaring ‘20s was the now-defunct Radio Corporation of America, or RCA. RCA was, as a stock, the Apple (AAPL) of its day. It crashed, as almost all equities did in the Great Depression, plunging from $505 to $26. It’s impossible to think of any scenario that would cause the present-day Apple to lose 95% of its value the way RCA did.

A century is a long time in the world of technology, and most public companies that are deeply committed to the radio business are doing poorly these days. Among six publicly traded radio companies described here, four are “old school” media companies that own as many as hundreds of radio stations in the United States and garner their revenue from selling advertising. The other two companies deliver music and words, but their stocks have been thriving.

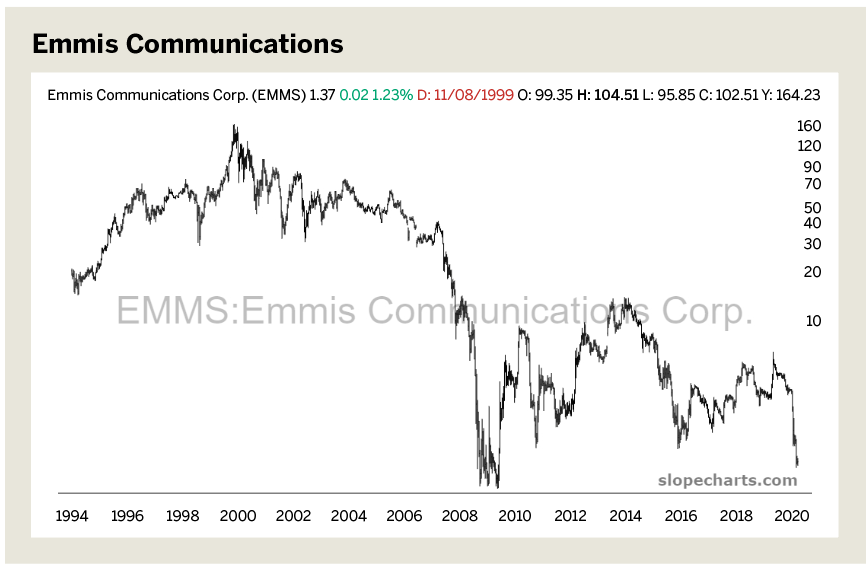

Emmis Communications (EMMS)

Emmis is the Hebrew word for truth, and the truth is that Emmis shareholders haven’t fared so well.

From 1994 through 2006, Indianapolis-based Emmis formed a tremendous distribution top, tumbling from its peak (adjusted for splits) of about $160 down to virtually a penny stock. Although its percentage gain from 2009 through 2014 was tremendous, it has returned to the lifetime lows it was experiencing at the depths of the 2008/2009 bear market. In short, this stock looks extraordinarily ill, having lost virtually all of its value.

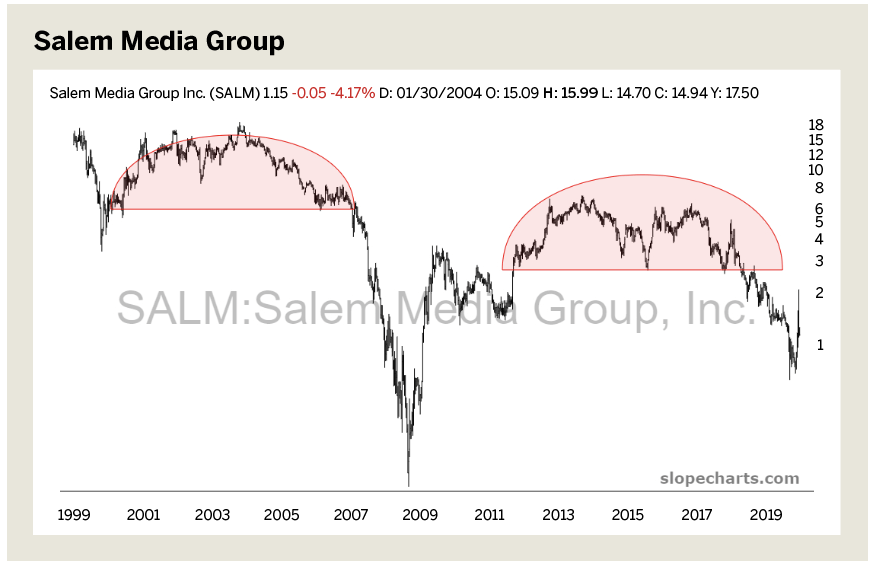

Salem Media Group (SALM)

Salem Media Group Inc., based in Camarillo, Calif., targets Christian audiences and focuses on “family-themed content and conservative values.” But there’s nothing divine about its recent performance.

Salem’s chart sports two nearly identical and very well-formed saucer tops. The first spanned 2000 to 2006 and was followed by the stock’s dreadful fall. Then it recovered most of its value, moving up many hundreds of percentage points in price. But from 2012 through 2018 another saucer pattern formed, which has thus far driven the stock price lower again. It seems altogether likely that the lows of 2008 may be revisited.

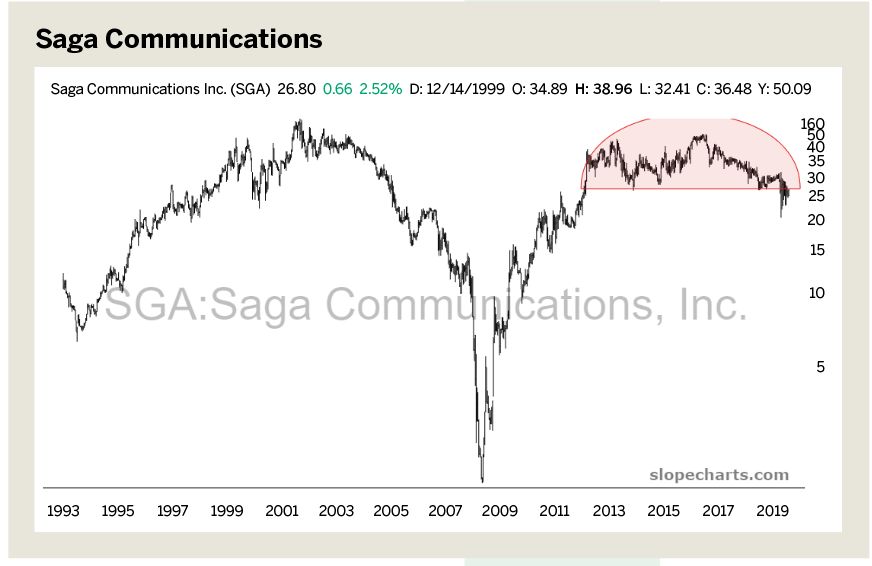

Saga Communications (SGA)

In Saga’s own words, “Radio is the heart of our being. We have a rich portfolio that spans 27 diverse U.S. markets comprising more than 100 brands. Radio continues to be the most efficient way for businesses to reach local markets en masse.” Like other public radio companies, its ownership of stations is geographically broad.

Saga has held up relatively well, compared with its peers. While losing about 50% of its stock price might not seem like an event worth celebrating, it’s far better than the virtual wipeouts that competitors have experienced. Traders looking for shorting opportunities might find this one of the more promising plays because the distribution top is so well-formed and, as of this writing, there’s still ample room for lower prices. One drawback, however, is that the stock is rather thinly traded.

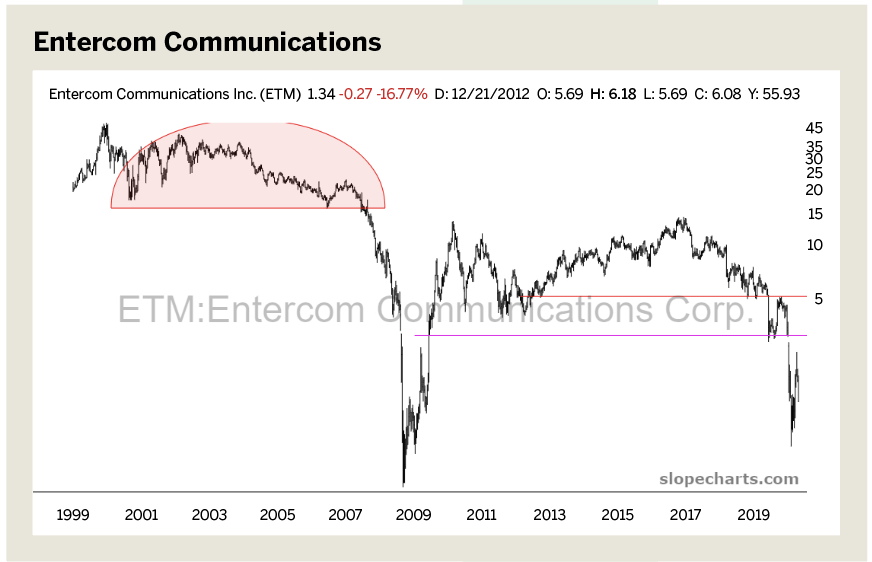

Entercom Communications (ETM)

Entercom Communications Corp., a market leader founded in 1968, owns 235 radio stations in 48 media markets. It’s the second-largest radio-based media company in the country.

Although they have different target markets, Entercom and Salem have similar charts. The saucer patterns and their timing are much the same, and they also share corresponding plunges in 2008 and 2020. As with many of the “old school” radio conglomerates, the equity has lost most of its peak market capitalization.

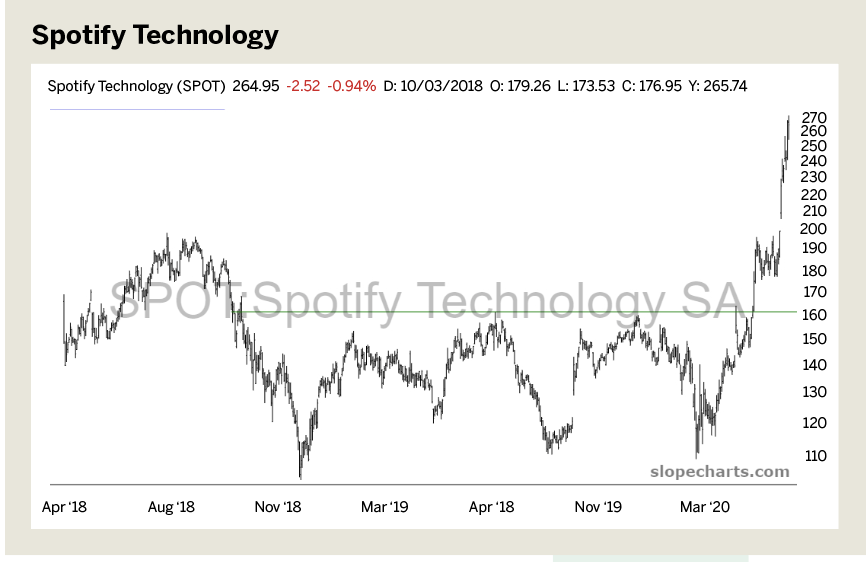

Spotify (SPOT)

Not all radio companies are suffering. Strictly speaking, Spotify isn’t a “radio” company because it doesn’t own hundreds of radio stations that broadcast radio waves to homes and cars. Instead, it’s a streaming audio service with an enormous library of music and podcasts.

The company uses a “freemium” model and its customers belong to two different groups. One group, totaling about 160 million users, uses the service for free in exchange for seeing or hearing advertisements on the site. For those users, Spotify seems much like traditional radio. The difference is that Spotify users can select precisely what they want to hear instead of simply tuning in to a station that plays music they tend to like and hoping a favorite song comes on now and then.

The other group, numbering about 130 million users, pays for subscriptions to Spotify. For a modest monthly fee they don’t have to deal with ads and they have unlimited access to Spotify’s music and spoken word library. Recently, the stock has been doing extraordinarily well.

Since its IPO in 2018, Spotify has progressed through three phases. During its first six months as a publicly traded company, the stock meandered aimlessly. From September 2018 until March 2020, it traded in a broad range from about $110 to $160, moving in a relatively cyclic fashion. In the spring of 2020, the stock exploded higher, nearly doubling in price in just a couple of months and reaching lifetime highs.

Pandora, a company somewhat similar to Spotify, was aquired in early 2019 by Sirius XM (SIRI) for $3.5 billion. That did not result in a terrific outcome for shareholders, who had seen Pandora’s value decrease by about 80% before the company was sold.

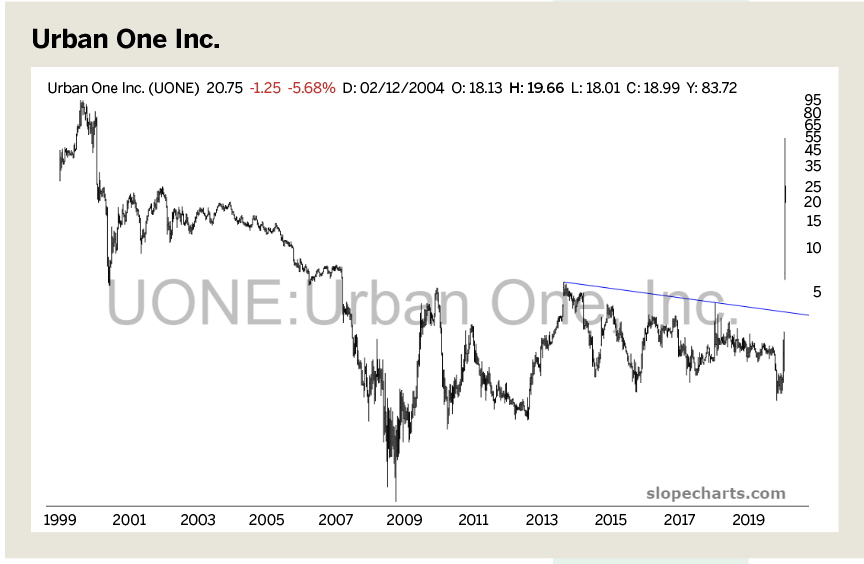

Urban One (UONE)

Another media company whose stock has been defying the “old school” radio doldrums is Urban One Inc. (formerly Radio One). Cathy Hughes started the Silver Spring, Md.-based media conglomerate in 1980, and its media properties target African Americans. In fact, Urban One is the largest African-American-owned broadcasting company in the United States, with 55 radio stations. It also owns most of the syndicator Reach Media. Urban One Inc.’s website is known as Interactive One, and its cable network is TV One.

Urban One is an extraordinary success story. From 1999 until 2009, the stock performed wretchedly, losing essentially all of its value. It recovered, in fits and starts, from 2009 through early 2020. As of this writing, a veritable mob of Urban One fans has swarmed into the stock, pushing it up thousands of percentage points in a short time. While that could mark a key inflection point for the equity’s performance, it would seem its recent behavior has more to do with momentum and online chatter than with any fundamental change in the company’s business prospects.

Broadly speaking, the radio business seems to be going the way of the VCR and 8-track tape. But the newer companies have oriented their distribution around technology and have captured the public’s imagination. Audio-based media organizations will always find a place in American culture, but the nature of those companies has changed drastically during the past decade.

Tim Knight has been using technical analysis to trade the markets for 30 years. He hosts Trading the Close daily on the tastytrade network and offers free access to his charting platform at slopecharts.com.