Slippery Oil Prices

Predicting the future price of black gold isn’t easy

The economy has apparently withstood this year’s 45% rise in the price of oil, but monetary policymakers remain concerned about the commodity’s future.

Higher oil prices can dampen demand in general, as consumers and businesses spend a larger portion of their budgets on oil-related products and less on other goods and services. Passing higher oil prices on to other goods and services can result in higher wages and cause inflation.

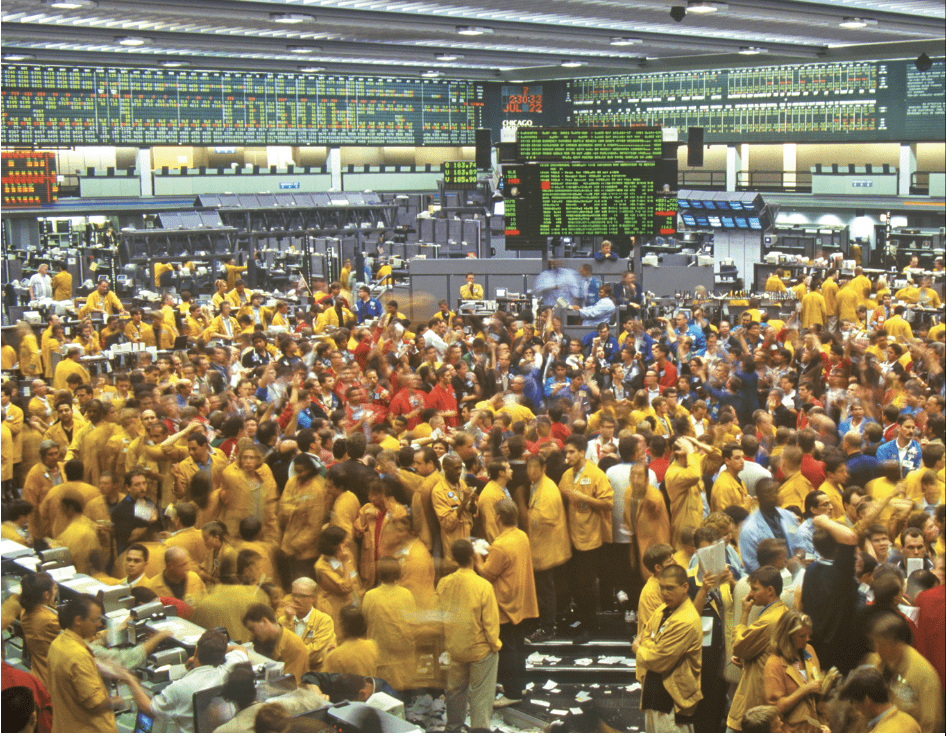

But is the price of oil likely to rise further or will it decline precipitously as it did in April 2020 in response to the pandemic? A natural place to look for an answer is in the markets, where oil traders know the industry and where their profits ride on making sound investments.

Perhaps traders can base forecasts of oil price movements on information from both the oil futures market and the spot market. To find out, forecasting exercises have been conducted to determine whether future prices of futures have predictive power in the present for the future pricing of oil.

Let’s review three ways of trying to determine future oil price movements.

1. The random walk model predicts spot oil prices will remain at current levels.

2. With the opportunity cost assumption, the current—or spot—oil price might help predict future oil price movements. Given certain simplifying assumptions, the opportunity cost of storing oil is the foregone interest rate. Therefore, in theory, the expected rate of return for holding oil should be identical to the interest rate. In other words, the price of oil is expected to appreciate at the interest rate. In practice, however, holding oil stocks often provides manufacturers advantages or offers flexibility in managing operational risks. Such benefits, commonly called “convenience yields,” should be reflected as a premium, mostly positive, in the current oil price. Thus, the expected rate of return of oil inventories may not be identical to the interest rate, and a forecast based on the current spot price may tend to over-predict future oil prices.

3. The futures-spot spread model uses the spread between the current futures prices and the spot price to predict movements in the future price of oil.

Oil futures prices reflect what the buyer and seller agree will be the price of oil upon delivery at some point in the future. So, those prices provide direct information on traders’ expectations for the future price of oil.

Like the price of every other risky asset, however, oil futures prices include risk premiums to reflect the possibility that spot prices at the time of delivery may be higher or lower than the contracted price.

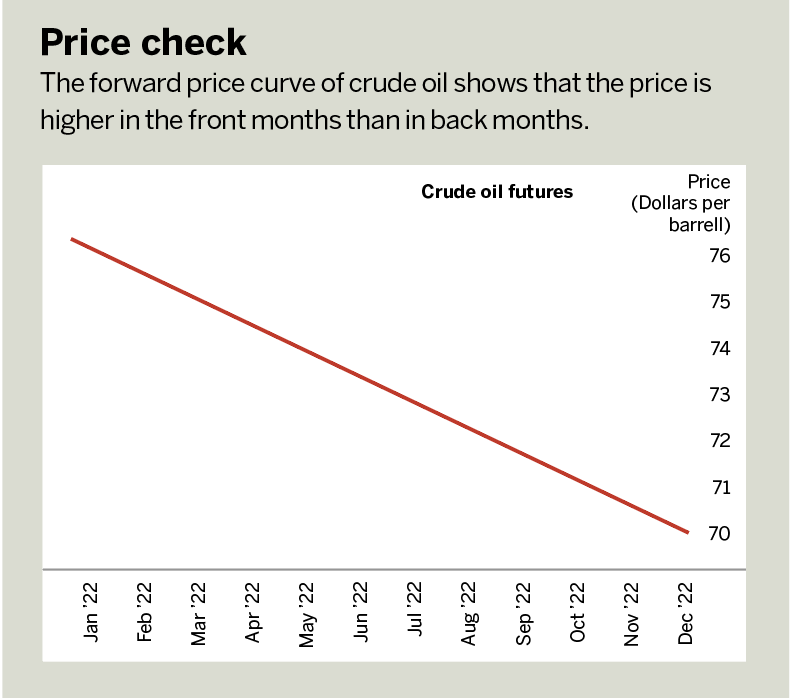

Traders can also use the forward term structure of crude prices to forecast prices. The shape of the futures curve is important to commodity hedgers and speculators. Both care about whether commodity futures markets are contango markets or normal backwardation markets. However, these two curves are often confused for one another.

Contango and normal backwardation refer to the pattern of prices over time, specifically if the price of the contract is rising or falling.

• Contango occurs when the deferred-month futures price is above the expected near-term futures price.

• Normal backwardation occurs when longer-dated futures prices are below the near-term or “spot” future price.

To test the accuracy of forward futures contracts to predict crude price, compare the three-month forward futures contract prices against where spot oil is actually trading in three months’ time.

For example, in August 2021, spot oil was trading at $71.26, and the three-month forward (the November contract) was trading at $69.15. But by November, spot crude was trading at $84.05, a difference of almost $15 from what the three-month forward “predicted” oil would be in November.

Oil futures prices contain important information about future oil price movements, especially for the near term. Considering the relationship between current spot and futures prices instead of considering only the raw futures price can possibly improve forecasting accuracy.

The variation between predicted and actual prices has no upward or downward bias, and in the one-year sample set had a variance in accuracy of almost 20%. Prediction errors are substantial, and accurately predicting the future price of oil seems as elusive as ever.

Pete Mulmat, tastytrade chief futures strategist, serves as host of Splash Into Futures on the tastytrade network. @traderpetem