3D Printing: A Hype Cycle Case Study

The public’s interest in 3D printers has waned because the devices failed to live up to the hype. What can that teach us about trading technology trends?

Whatever happened to 3D printing?

It was supposed to be in every home in America by now, busily cranking out all the tools, human organs and automobiles anyone could ever want or need. Clearly things haven’t gone as planned.

But studying the 3D saga can at least provide some insight into how hype and human psychology play out in the public arena of ticker symbols.

Consultants at the Gartner Group have come up with a five-stage “hype cycle” to explain what happens with new technology.

The model drew criticism for its allegedly unscientific lack of rigor and its supposed dearth of hard data, but it provides an interesting narrative for the stories of “hyped” industries.

The five stages are:

1. Innovation Trigger

2. Peak of Inflated Expectations

3. Trough of Disillusionment

4. Slope of Enlightenment

5. Plateau of Productivity

It would seem 3D printing has descended into the Trough of Disillusionment. Consumers feel discouraged, startups have failed and the future seems uncertain.

Trigger to trough

The first stage of 3D printing, the “innovation trigger,” took place in October 2009, more than a dozen years ago. That’s when a man by the name of Bre Pettis introduced what he called “a box with wires” and named it MakerBot.

Retailing for about $1,000, it was the first 3D printer with a price low enough to appeal to consumers. A quarter of a century after the first patent for 3D printing, people could finally afford to “print” something physical in their own homes.

The hype machine swung into action. The media raved about this revolutionary new technology and predicted that in just a few years, people would be able to print just about anything imaginable—up to and including houses.

Hobbyists and serious technologists jumped feet first into the new realm of 3D printing. But with very few exceptions, they used their new peripherals to print out only the easiest and most instantly gratifying things possible. They made little toys, knick-knacks and simple models.

Those early adopters soon found they could print only so many trinkets before the process seemed pointless. As reality set in, they began to sell their seldom-used 3D printers. These were some of the problems:

⊲ Printers that sell for $1,000 aren’t made with professional-quality parts. Manufacturers have to cut corners to make them that affordable.

⊲ The early printers were based on new technology that required users to have a fair bit of hobbyist skill, much like radio in the 1920s and computers in the 1970s. To function well, the printers required nearly constant calibration.

⊲ There weren’t many useful objects that people could print at home, unless they knew computer-aided design and had the requisite software. Almost nothing but silly, useless trinkets materialized at the end of a time-consuming print cycle.

Thus, the “peak of inflated expectations” came and went swiftly for 3D printing. Consumers felt they had bought something that fell far short of expectations, and their 3D printers became idle dust collectors.

In public markets

Personal computers first appeared in 1975, but it took a full five years for any companies in that industry to hit the public markets. These days, the world of high-tech is so mature and offers so much financial opportunity that it took very little time for 3D printing companies to go public.

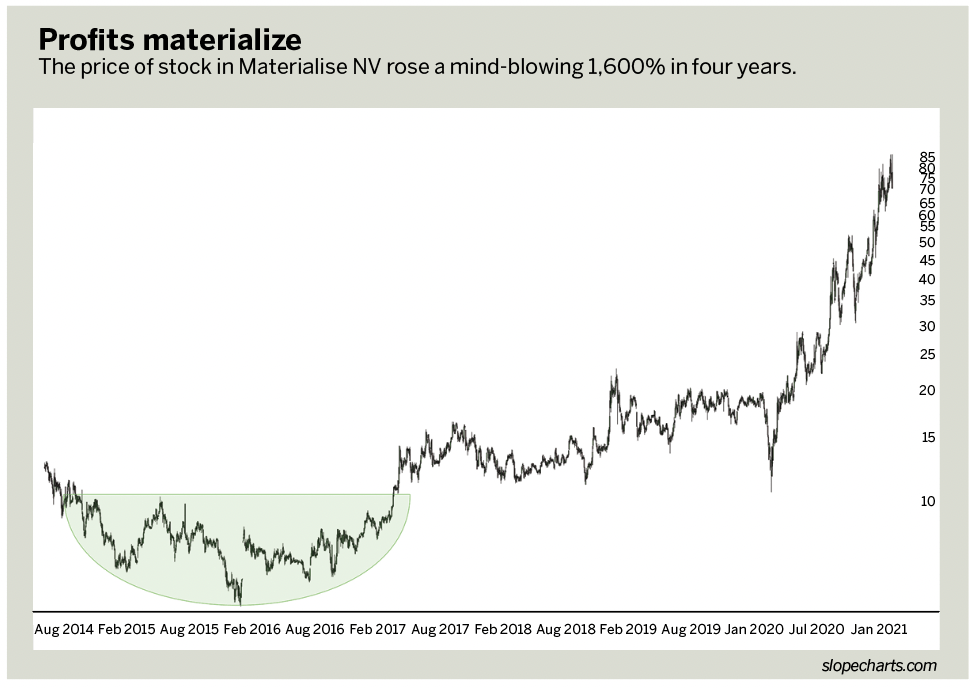

A good example, Materialise NV (MTLS), formed an exceptionally clean saucer pattern (tinted in green) and ascended from about $5 to about $85, an astonishing 1,600% rise in price, over four years.

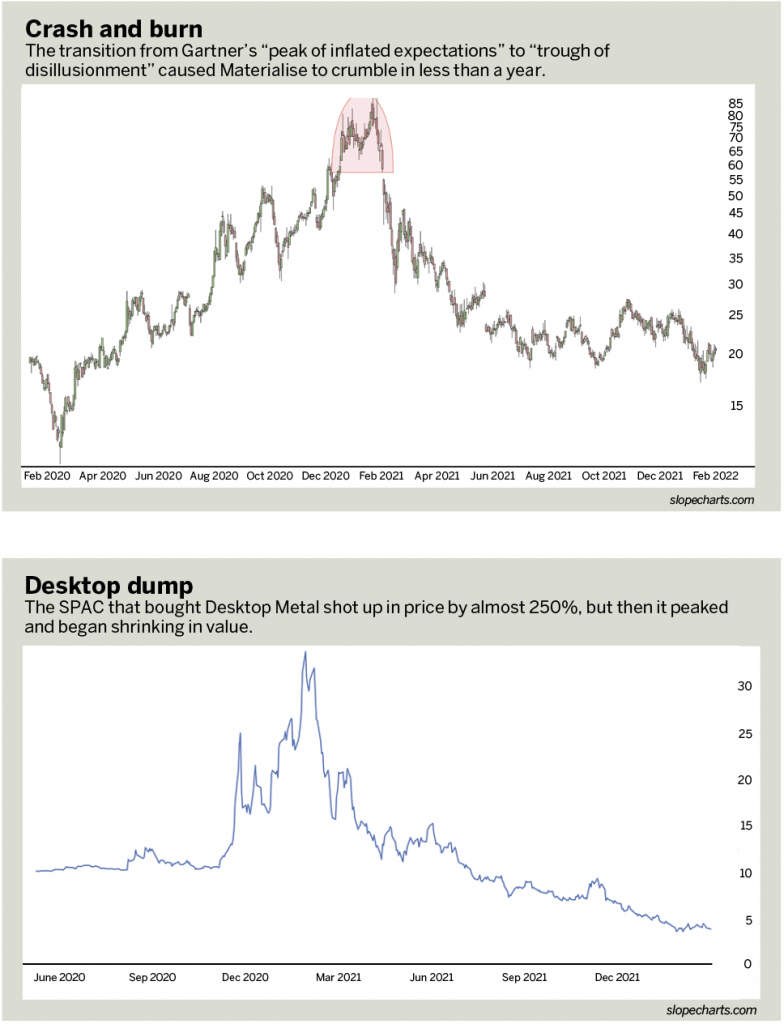

But the transition from “peak of inflated expectations” to “trough of disillusionment” can be devastating for equities, and thus Materialise crumbled from $85 to $20 in less than a year.

A similar situation played out with Desktop Metal (DM). The special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) that bought Desktop Metal was trading at about $10 before latching onto the 3D printer firm.

After the purchase, the stock swiftly ascended by almost 250%. However, Desktop Metal peaked in February 2021, just the way Materialise did, and it shrank in price from about $34 to a mere $4, representing a nearly 90% wipeout.

These stocks have become dust collectors—just like the printers themselves.

Volume tells the story

Hype attracts attention and inspires feelings ranging from excitement to rancor. Those emotions find expression in the volume of stock traded in the public markets. Positive press and word of mouth make a large number of investors want to join in on the fun and reap the profits.

But like most phenomena in the trading world, hype can be a double-edged sword. Take the example of Cathie Wood’s Ark 3D printing exchange-traded fund (ETF), which trades under the ticker PRNT and tracks the performance of the “Total 3D Printing Index.”

The volume for this ETF had been modest for its entire history, but it began to receive a tremendous amount of attention in March 2020. That caused it to triple in price in less than a year, peaking in February 2021.

As the volume portion of the accompanying chart illustrates, the higher the price went, the more active the fund became. Larger and larger sums of money piled into the fund. Success begets success, particularly in the world of tradable instruments.

Once this phase of the hype cycle was completed, however, PRNT did precisely what it was supposed to do: track the index value of the component companies. Thus, it went on to lose more than half its value in a year’s time.

Long-term holders were still all right, but the majority of owners (represented by the swelling volume of the stock while its price was peaking) faced unexpected losses, whether realized or not.

Indeed, the highest volume for the fund in its entire history came on Feb. 8, 2021, and the fund peaked literally the very next day.

Revival or denouement?

Given the disillusion that pervades the consumer market for 3D printing, the massive plunges in stock prices and the discord among early adopters, some might feel it’s time to pronounce the product dead.

But not necessarily. The technology seems to work well in two sectors: education and engineering.

Rapidly prototyping a physical product from a desktop computer proves invaluable to engineers creating anything from automotive replacement parts to surgical devices.

Operating 3D printers also teaches students a lot about writing computer code.

No guarantees

Progressing through the first three phases of the hype cycle by no means guarantees 3D printers or anything else will continue into the the final two phases and thus achieve success in the marketplace.

Examples abound. In the early 1950s, lots of Americans were convinced they’d soon pick up their groceries in nuclear-powered automobiles. That was just one among many revolutions that were nothing more than hype.

Yet 3D printing doesn’t seem far-fetched. And combining the design power of a computer with the magic of a printer could easily capture the public imagination again. All it will take is that “killer app.”

Tim Knight has been using technical analysis to trade the markets for 30 years. He’s the host of Trading Charts with Tim Knight on the tastytrade network and offers free access to his charting platform at slopecharts.com. @slopeofhope