State of the Arts

The art market is booming, but most people can’t afford Picasso or a Basquiat. Here’s why they should pay attention anyway.

Don’t worry about understanding abstract paintings or learning to appreciate sculptures. Just think of

the high-end art market as an economic indicator that no one really talks about.

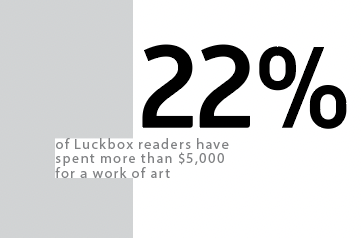

Indifference to the niche market isn’t wholly unreasonable. Less than a quarter of U.S. adults visited art exhibits five years ago, according to the National Endowment for the Arts. Considerably fewer ever get the chance to own fine art.

In fact, despite tens of millions of art transactions each year netting tens of billions of dollars, Larry’s List research from 2015 put the number of worldwide art collectors—defined as people who regularly buy substantially priced artwork—between 8,000 and 10,000. For context, if every collector on Earth brought two friends to the Boston Red Sox’s Fenway Park, there would still be close to 8,000 empty seats.

With so few people dominating so much of one market with such a high barrier to entry, it’s easy to overlook the fact that the prices fetched by blue-chip art say a lot about the global economy. More specifically, because of the market’s unique supply-and-demand dynamics, surging art prices imply surging fortunes for the world’s most affluent.

“It is indeed the wealth of the wealthy that drives art prices,” concluded a 2009 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research. “This implies that we can expect art booms whenever income inequality rises quickly.”

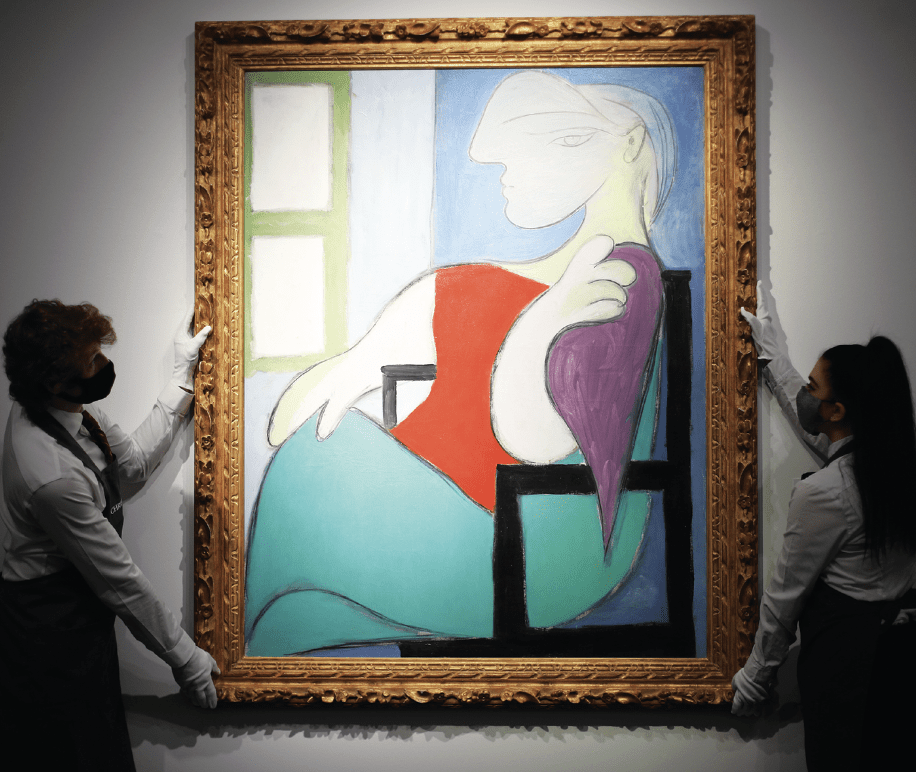

How does that work? Unlike most assets, both supply and demand for art can be inelastic. Pablo Picasso painted only one Woman Sitting Near a Window. He can’t paint another, and there are no substitutes. A hopeful buyer hell-bent on owning it just needs more disposable wealth than everyone else who wants it, which, in the case of that painting, was $103.4 million when it sold last May.

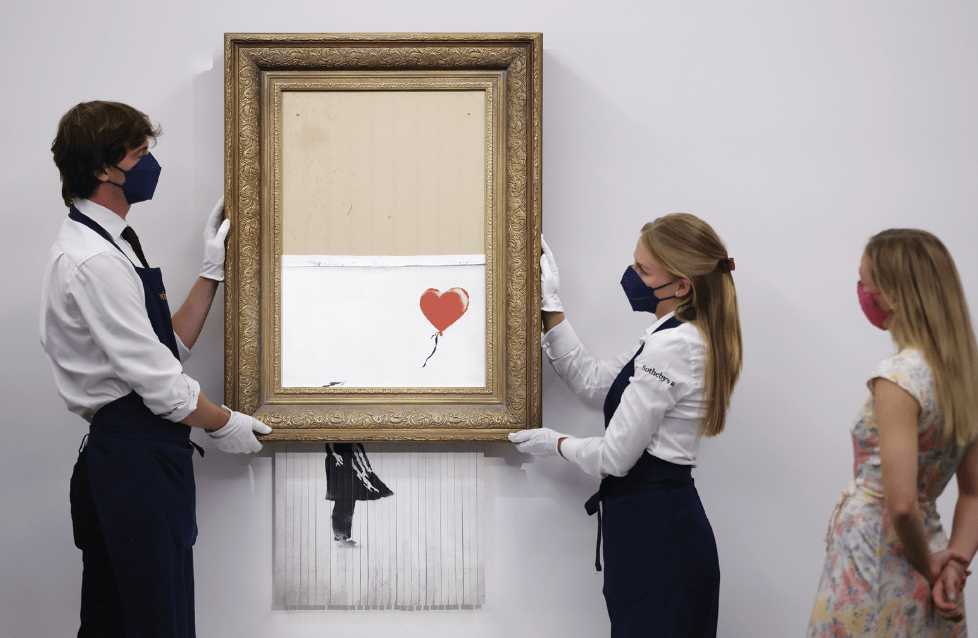

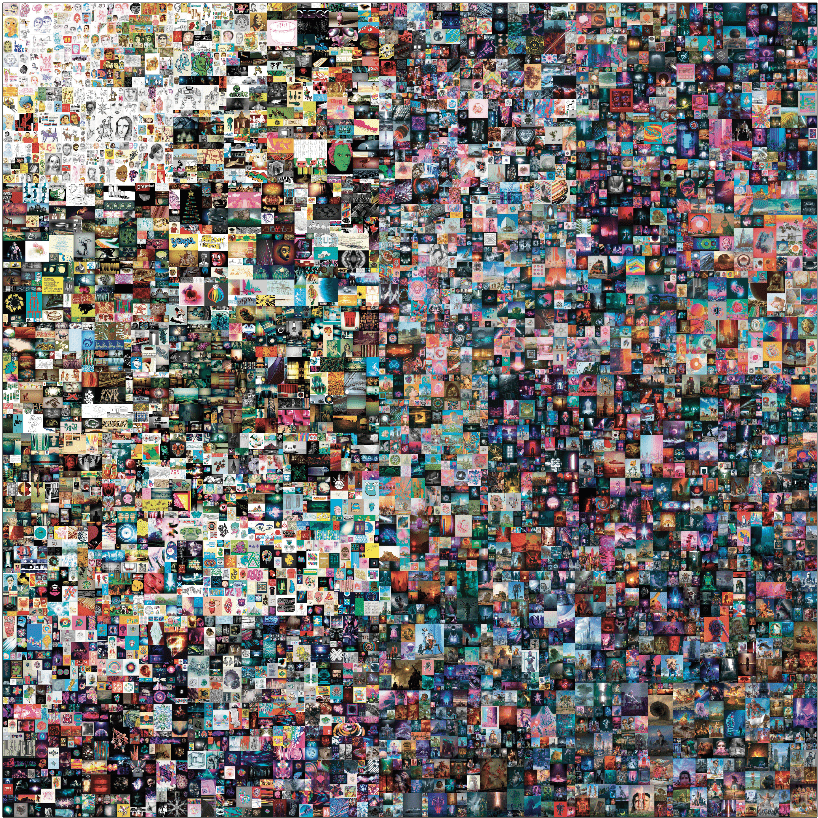

Art auctions set a $6.5 billion sales record last year, and buyers regularly paid prices that dwarfed auction house estimates (see “High Art”). All signs point to an ongoing art boom that may have predated the pandemic.

“It absolutely has been heating up in the last couple of years,” said Megan Fox Kelly, president of the Association of Professional Art Advisors. “In 2019 it was an extremely strong market. It was even more so in 2020, which, of course, surprised us.”

The onset of the pandemic threw art advisors, gallerists, private dealers and auction houses into a panic, Kelly told Luckbox. All of those players in the art world doubted that digital viewings and online auctions would spur high-level buying. In practice, the opposite proved true.

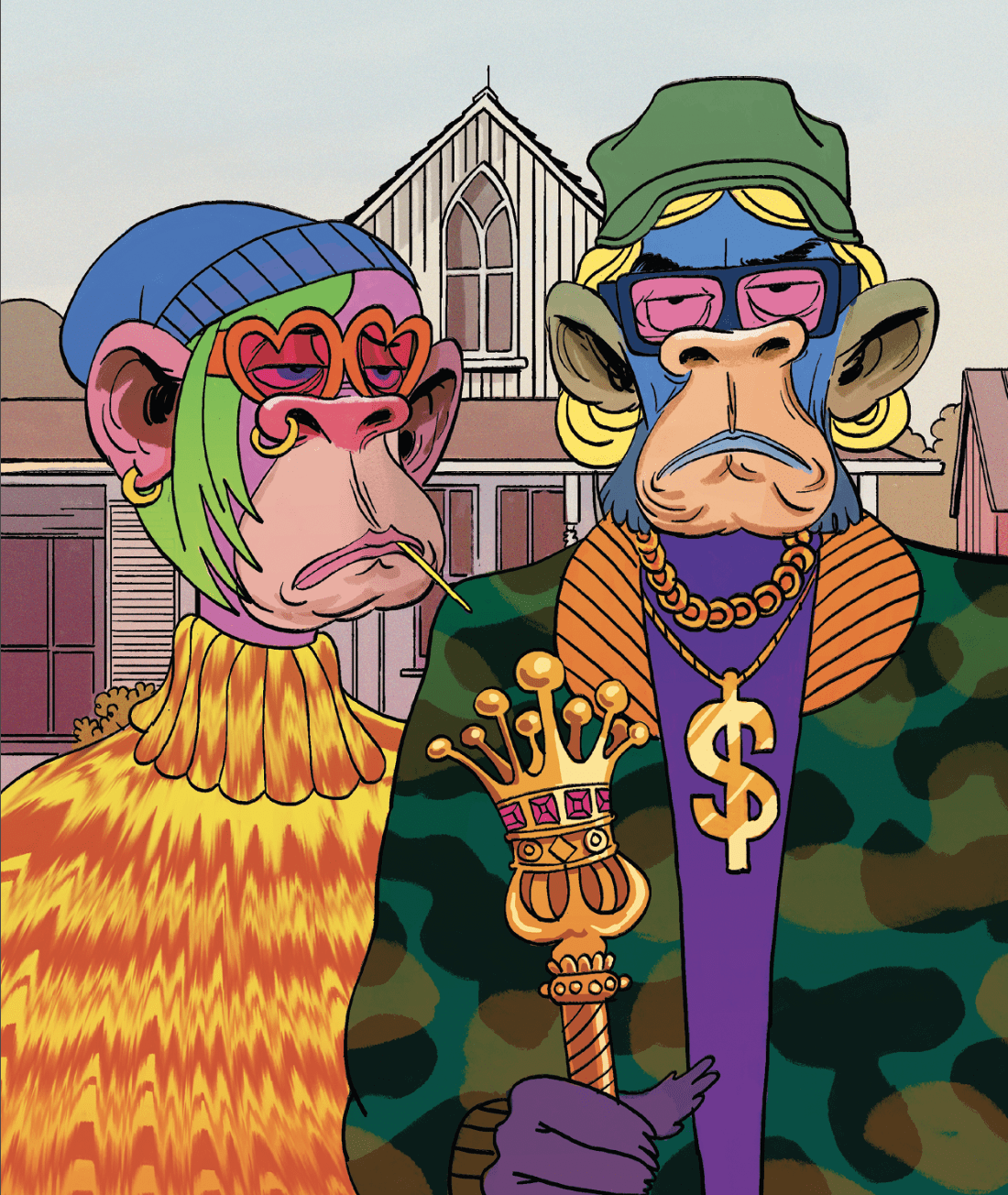

New collectors were entering the market, established collectors were ramping up their buying and the market was expanding in Asia. In fact, collectors in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan accounted for 40% of the contemporary art market’s value in 2021, according to artprice.com’s Contemporary Art Marketreport. That amounted to an 8% edge over the United States.

“I do think that there are more people participating at a very high level in the market, and so there is more competition for these lots,” Kelly said. “It’s competition that drives bidding that drives prices.”

In other words, the art market truly reflects simple supply and demand.

But why, especially amid a pandemic, is the art market booming? What artistic trends have emerged, and is the boom sustainable?

“COVID has changed everything,” said Georgina Adam, editor-at-largeof The Art Newspaper and author of The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum. “It’s sort of blown up the art market and, of course, it’s absolutely accelerated the fortunes of the richest, which I don’t think we expected when it started.”

A special issue of Forbes drew attention to that phenomenon when it tracked a record 493 new billionaires last year, or about one new billionaire every 17 hours. The magazine cited initial public offerings, special-purpose acquisition companies, cryptocurrency and COVID-related healthcare

as the most prominent new paths to wealth.

“Art has become—and this has really been this century—a trophy purchase and a trophy acquisition,” Adam told Luckbox. “One of the things people don’t really realize is that if you’ve got a really enormous amount of money, there’s not much that you can actually spend it on that gives you bragging rights.”

Enter blue-chip art

Moreover, while cars, houses, jets and other luxury goods typically depreciate in value over time, art—albeit not in all cases—has a well-founded track record of price appreciation. A Citi Private Bank report found that the art market as a whole produced an annualized return of 5.3% between 1985 and 2018.

So, where’s the new money going? Kelly and Adam agree that historically underrepresented groups of artists have exploded in popularity—a trend Kelly said is “very conspicuous and overdue.”

Although the top end of the market is still filled predominantly with the works of white men, the majority of living artists setting auction records over $1 million last year were women and artists of color, according to artsy.net. Among them were Avery Singer, Lisa Brice, Flora Yukhnovich and Stanley Whitney.

But art booms are nothing new. History buffs are likely familiar with the vast art collections of American industrialists during the Gilded Age. More recently, the ’80s were marked by a boom in the arts. Now, many are wondering if the current boom can last.

“If some event affects the world’s economy, it will inevitably affect the art market as well,” Adam said, citing natural disasters and geopolitical uncertainty. “If none of those things happen, I do think the art market is pretty secure at the top end for the foreseeable future.”

Oprah’s Art of the Deal

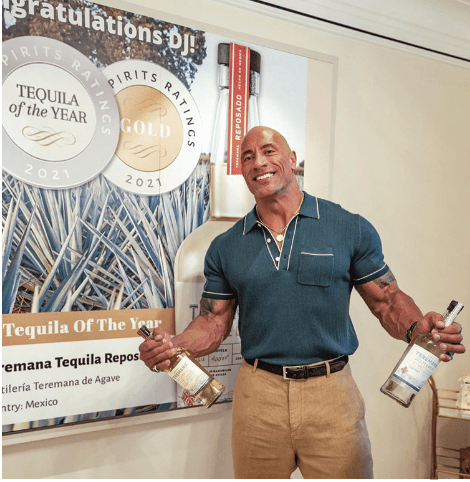

High-end art costs too much for most people, but not for celebrities like Jay-Z, Madonna and Leonardo DiCaprio.

Still, it was Oprah Winfrey who made headlines in 2017 when it was revealed that she made one of the biggest private art deals of the prior year. She sold Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II for $150 million to an unidentified Chinese buyer about a decade after purchasing it for $87.9 million.

Winfrey’s ownership of the 1912 painting marked just one chapter in its remarkable history. Stolen by the Nazis during World War II, it was displayed in Austria’s Österreichische Galerie Belvedere museum until a legal battle returned it to an heir of Adele Bloch-Bauer, the painting’s subject, in 2006.

Winfrey bought the work from the heir at a Christie’s auction a few months later.

The struggles surrounding that painting, as well as four other Klimt works, were immortalized in the 2015 biographical drama Woman in Gold starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds.

“Bad” Art Rising

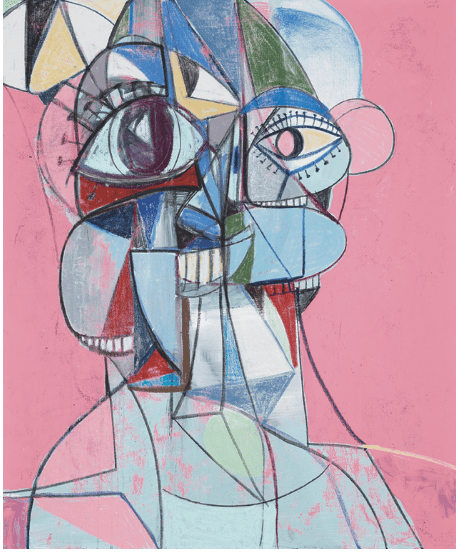

The art world has embraced styles as varied as surrealism, abstract expressionism, pop art and conceptual art. But now it’s making room for painting described simply as “bad.”

Art market journalist Georgina Adam told Luckbox that figurative works and the conscious rejection of traditional art norms have been gaining traction. The emphasis is less on care and accuracy and more on “painting more as a child would,” she said.

“Remember, Picasso said it took him a lifetime to learn to paint like a child,” Adam noted.

Popular artists who embody the style include Rose Wylie andTschabalala Self.