The Epic Saga of FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried

How It Started, How It’s Going…

FTX was the world’s second-largest cryptocurrency exchange.

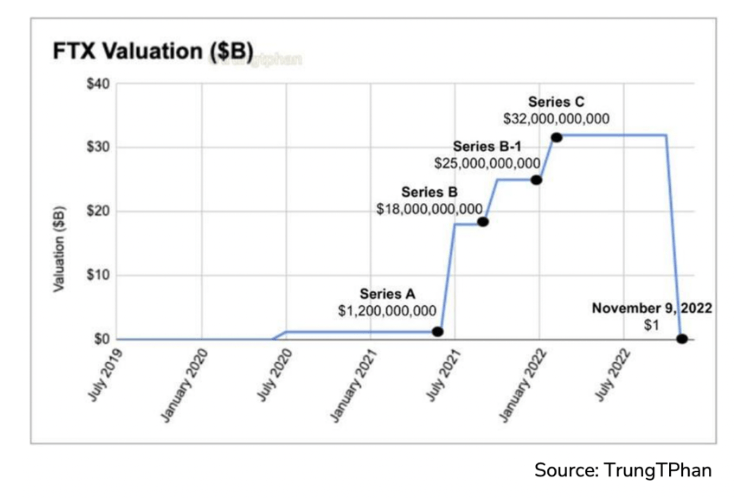

On Nov. 11, FTX – valued at $32 billion – filed for bankruptcy.

It had an $8 billion hole in its balance sheet.

For anyone watching this – its demise was the only thing more shocking than its ascension.

FTX came out of nowhere in recent years.

It was incorporated in Antigua in 2019.

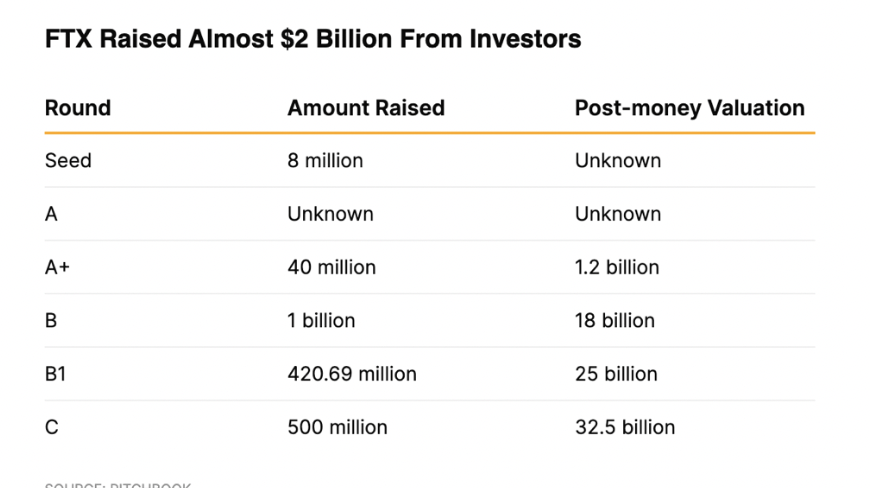

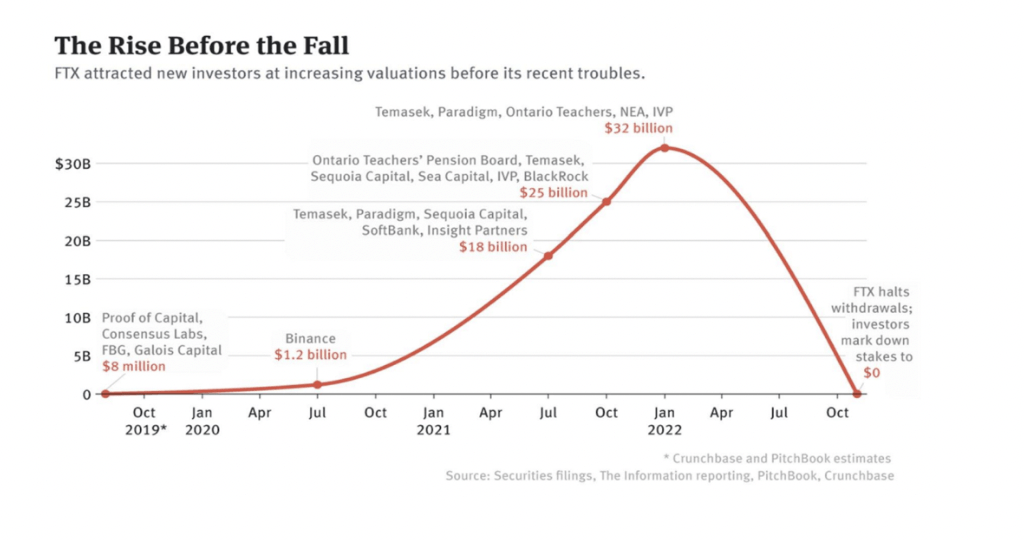

It was a private company headquartered in the Bahamas, and it curried deep political favors for entities and politicians across that nation. In recent years – it raised capital at increasing and staggering valuations. It went from a B round in 2021 at an $18 billion valuation to its most recent C round in 2022 at a $32 billion valuation.

By comparison – Coinbase (the third largest cryptocurrency exchange and a public U.S. company) was founded in 2012. Coinbase currently has a market capitalization of $13 billion but went public last year with a valuation of around $86 billion.

If you watched the World Series – two weeks ago – FTX’s logo was on the umpire’s uniforms. This was the first effort ever to put advertisements on umpire uniforms. It was monumental.

FTX’s name was on the arena where the NBA’s Miami Heat play. I was just at a concert there six weeks ago. And it was impossible not to know that FTX was the bearer of that sports arena.

The deal – recently canceled by the Heat – was for 19 years at roughly $135 million.

Over three years, FTX burst into the mainstream with aggressive public exposure (it spent $20 million on Super Bowl ads). It signed strategic partnerships like the ones with Skybridge Alternatives, Mercedes, Major League Baseball, Visa, and Tom Brady. And it introduced new protocols that attracted leading projects to its exchange and its CEO-centric ecosystem.

Its CEO and founder: Sam Bankman Fried (or SBF), a 30-year-old MIT alum with a degree in physics. Before becoming an entrepreneur and a trader, he worked for the Centre for Effective Altruism at UC Berkeley for two months (the theme of altruism is very important).

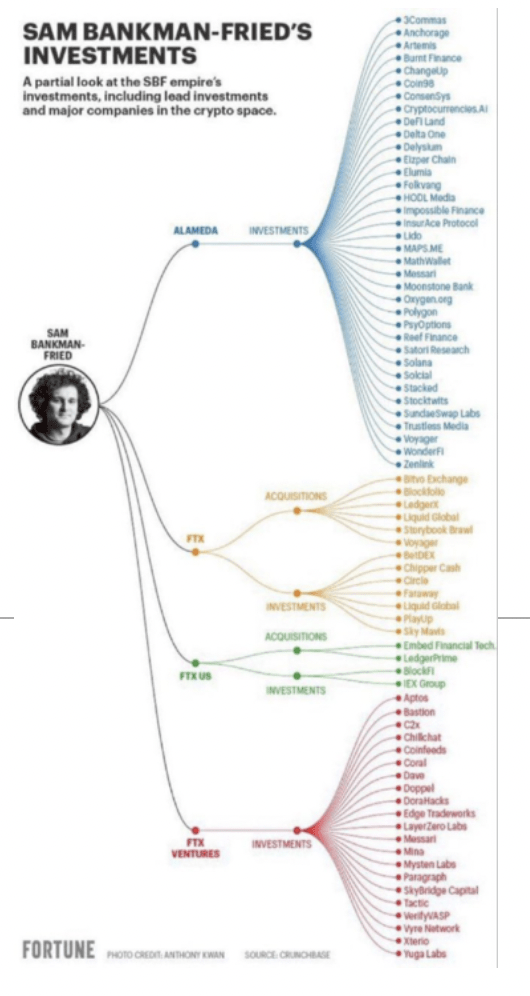

By 2017, SBF launched a trading fund called Alameda Research, named after the California county in which Berkeley is located – even though its headquarters ended up in Hong Kong.

The fund’s strategies included arbitrage, market making, yield farming, and trading volatility.

Two years later, SBF founded FTX.

These two companies are essential – since they’re the main characters in this drama.

Please keep this in mind.

BF owned Alameda Research, a trading company that engaged in the following:

- Market making – they bought and sold crypto assets and traded in their accounts.

- Yield farming – the process of incentivizing people to put their assets into a pool and offering them interest… SBF later described this process as one based on a delusion.

- Arbitrage – trying to exploit price inefficiencies between various exchanges or buyers and sellers. It’s a common strategy for hedge funds but odd for an exchange’s parent.

- Trading Volatility – No explanation necessary, and good luck with that in 2022.

So, SBF owns FTX – a cryptocurrency exchange, and Alameda, which trades assets.

That screams “conflict of interest.”

While people knew these relationships existed… it wasn’t something that found its way into mainstream financial media coverage around FTX. That’s where it all crashed down.

SBF Becomes the White Knight

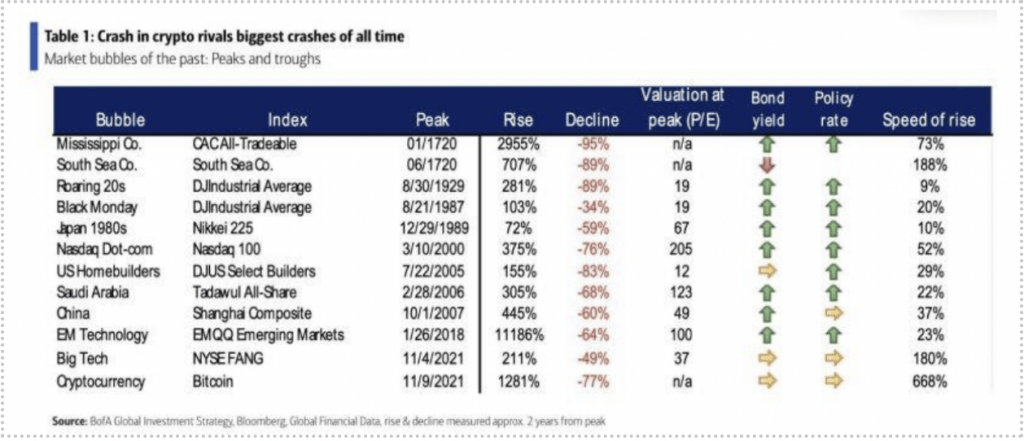

Cryptocurrency investors and traders were on edge in 2022. Bitcoin has lost about 65% of its value over the year. But there were also very serious problems that fueled the collapse of cryptocurrency hedge fund Three Arrows Capital and crypto broker Voyager earlier this year.

Allegations persist that Three Arrows was structured like a Ponzi Scheme, and others have accused Voyager Digital of fraud, according to lawsuits. Voyager had ties to Alameda Research. The hedge fund offered Voyager a $485 million loan earlier this year.

In fact, SBF also was engaging in a variety of cryptocurrency bailouts this year. At best, the argument goes that he was being “altruistic” and trying to save the cryptocurrency ecosystem. At worst, critics argue that he aimed to build a monopoly by propping up the other exchanges and companies – and negotiating deals allowing him to buy them later.

In August, he told David Rubenstein of Carlyle Group on his show that he had effectively thrown away $70 million trying to help Voyager Digital.

He had a $400 million revolving credit deal with BlockFi, which gave him the right to buy the platform at a price ranging up to $240 million. When one digs deeper into that BlockFi agreement, things get problematic. BlockFi was forced to move its customer deposits over to the custody of FTX. When BlockFi employees asked questions, senior executives at the company told them to stop doing so.

In May, he also bought nearly 8% of Robinhood Markets (HOOD) – a stock and crypto exchange popular among younger traders that relied on the vilified practice of Payment for Order Flow as its primary source of revenue. Robinhood went public in 2021 and remains unprofitable. SBF bought its stock at under $7 per share.

SBF was now the face of the entire cryptocurrency market and its white knight.

Even Jim Cramer (it’s always Jim Cramer) described him as… The New JP Morgan.

But while tossing all this money around, SBF publicly acknowledged the industry’s problems.

He said in June that more exchanges would fail. This was a bit confounding – given that he was throwing so much money at the industry. In April, he was also a little too candid about the nature of the business activity of yield farming – a practice of Alameda. I’ll discuss this later – but he occasionally and perhaps unintentionally entertained the fears of crypto critics.

That said, FTX was – it seemed – on pace to create a monopoly due to its never-ending stream of capital and ability to negotiate deals with struggling enterprises at favorable terms.

This company grew at a breakneck pace, yet it largely avoided regulatory oversight from the United States from its Bahamas headquarters, just a 30-minute flight from Miami.

You see, the cryptocurrency industry is unregulated.

It is tough to determine risk in this market, which makes the volatility trading practice challenging. There isn’t a regulatory framework that requires market makers to report to agencies like The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). There isn’t much transparency, despite so many promises of it.

There aren’t clearinghouses that would help us understand the total risk in the system.

There are also extensive “chain of custody” problems – including a lack of enforceable contracts – plaguing the world of yield farming in cryptocurrency. I’ll explain soon how SBF honestly, but perhaps unintentionally, described how yield-farming mimics a Ponzi scheme.

Yes…that happened.

So, Here’s How This All Unfolded

FTX’s exchange allowed the trading of futures for dozens and dozens of cryptocurrencies.

It allowed users to trade perpetual futures (no expiration date). You could trade options, prediction markets, and tokenized assets (effectively derivatives contracts).

But it also had its own exchange token.

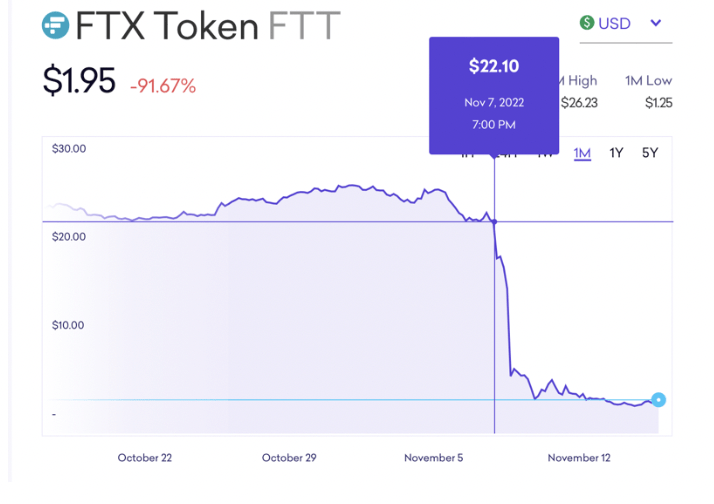

FTX created a crypto token asset called FTT.

This crypto is significant to our saga…

FTT was the “native” token of the FTX cryptocurrency exchange.

Why have this? Well, it’s a money grab. But it’s also a specific engagement tool that draws people into the exchange – and keeps them there because of its perceived value.

This token gave FTX users access to various features and services (including discounts on trading). So, people who hold this FTT receive discounts on fees. That – by basic logic on volume – was a good incentive for people to invest in this token.

The more you own FTT, the bigger the discounts. (Don’t worry, there’s a lot more to this.)

If you owned a lot of FTT and referred people to the exchange – you’d get better deals. You could withdraw ERC=20 / Ethereum (the second largest cryptocurrency by market capitalization) tokens up to 1,000 times a day for free (this was important for blockchain developers.) And people could occasionally get “airdrops” or bonuses like free cryptocurrency at any time. So, maybe you wake up one day, and you get free “money.”

One last thing – this FTT token allowed people to trade with 3X leverage.

So – there were billions of dollars in these tokens (all these tokens were exchanged through customer deposits made in either fiat currencies or other cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin). But remember, these assets aren’t properly regulated, and – as SBF would later explain – properly valuing them is difficult. It’s primarily based on – the madness and behavior of crowds.

The FTX Hell Week in Review

So, the countdown clock of FTX’s demise looks like this. Here’s what happened in 10 days.

On Nov. 2, someone leaked a balance sheet from Alameda, which showed that it owned a sizable amount of this FTT token. That was a red flag for the trading community. People knew about the relationship between Alameda and FTX. Their relationship is like JPMorgan Chase and JPMorgan Asset Management.

They were supposed to be “Chinese walls” between the two entities. Of course, we all know those Chinese walls sometimes have windows. (The 2008 Goldman Sachs saga involving one of its linked funds and John Paulsen selling worthless assets to the public was well known. It was the central plot device in the financial crisis movie Margin Call.)

On November 5, three days later, Whale Alert – a crypto-tracking social account – noticed that about 17% of all FTT in circulation – had transferred over to an account at Binance – the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange.

A day later, Alameda’s CEO Caroline Ellison (who doesn’t inspire much confidence) claimed that the balance sheet of the hedge fund didn’t reflect its holdings. Now, it’s worth noting that Caroline didn’t have any experience in leadership. And the previous co-CEO of Alameda resigned in a series of tweets on Aug. 24, 2022. (CoinDesk later reported that the entire empire of FTX was run by “a gang of kids in the Bahamas.” Fortune said that most were former employees at quant firm Jane Street or came from MIT. The report noted that all 10 “are, or used to be, paired up in romantic relationships with each other.” And Forture’s sources say that Ellison “at times has dated Bankman-Fried.”)

Ellison’s statements on Nov. 6 didn’t convince the market, and various fund managers started worrying about FTX and the underlying token FTT. We’d seen this drama unfold before, and some people headed for the exits. (Meanwhile, Twitter started to spread a viral video of her saying: “I don’t think stop losses are a good risk management tool.”)

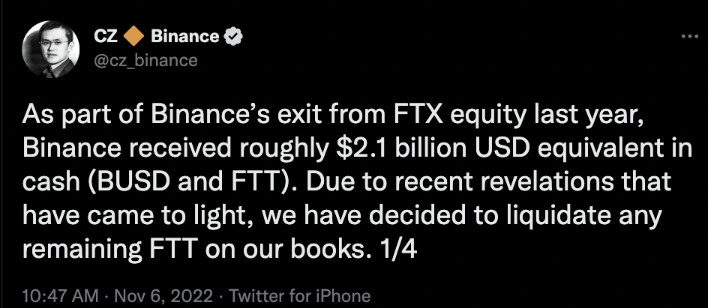

The next day, Binance’s CEO Changpeng Zhao announced that his company would sell all its FTT holdings. That was about $2.1 billion in FTT. Binance had these tokens from its divestment in FTX in 2021. Binance was an early investor in FTX. Then it became a friendly competitor. Combined, the two exchanges processed the bulk of global trading.

Zhao said that this was not about attacking a competitor – and he said in the string of Tweets that the process would take a few months and that they were liquidating and warning to try to do so in a way that had “little market impact.” (Oops…) Some people were skeptical about this – and accused Zhao of striking down FTX when it was weak. Some also compared this situation to one hedge fund trying to initiate a short squeeze on other market participants.

There was speculation that this selling was linked to “recent revelations that have come to light” about the Alameda balance sheet. But some people on Twitter charged that FTX had spoken negatively of Binance to U.S. regulators – and that this had gotten back to Zhao.

After Zhao announced it would sell its position publicly, Alameda offered to buy Binance’s position at $22 per token. But that deal never came. The following day, Binance turned down the offer and said the company would remain in the “free market.” This set off a panic.

Mark Moss says that Caroline Ellison’s statement that they’d pay $22 implied Alameda’s margin levels. Did she understand what it meant that the specific $22 was a signal to the market – and it allowed sharks to swim around those levels? Because the second that FTT broke under $22, it went into a direct freefall.

Prominent community members were active on Twitter telling investors to pull money from FTX. That included Ran Neuner, CEO of On Chain Capital. By Nov. 7, there was $451 million withdrawn in seven days.

People started having trouble getting money out that day. But FTX told everyone that things were operating smoothly. SBF went on Twitter saying that a competitor (Binance) was trying to undermine them with “false rumors.”

“FTX is fine. Assets are fine,” he wrote.

In addition, SBF said that the company didn’t “invest client assets” – a sudden statement that raised serious questions about the legality of its operations. SBF would ask Binance to work with them for the good of the cryptocurrency world. It was, again, appealing to altruistic natures.

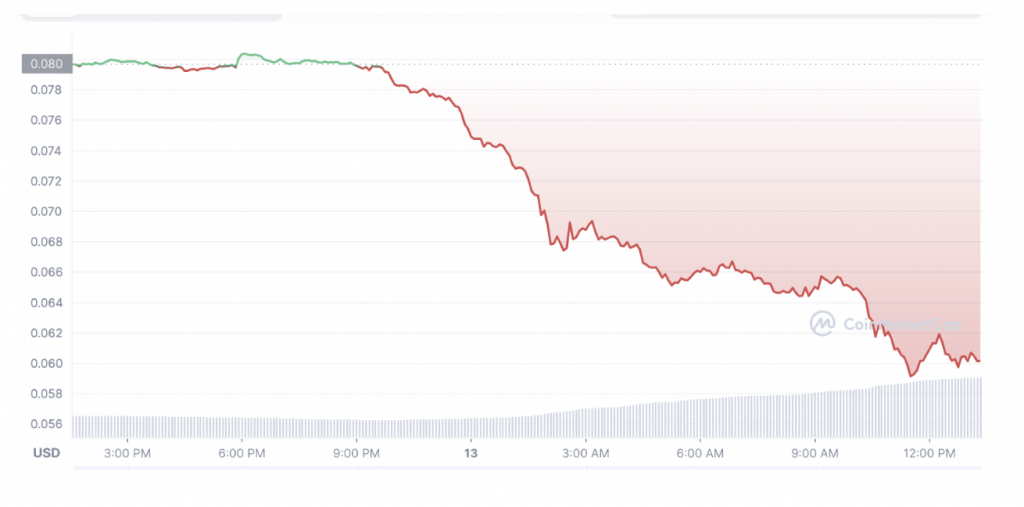

The following day, the FTT coin plunged by 30% – and Bitcoin cratered on concerns about liquidity in the cryptocurrency market and the stability of FTX. In a crunch and unable to find the necessary capital, SBF announced he would sell his company to Binance.

That deal wasn’t binding. Binance made an explicit point to publicly note that it could “pull out from the deal at any time” based on its due diligence, which it promptly started. Behind the scenes, Coinbase’s CEO said he had advised against the deal for Binance.

The next day, things went from bad to worse. Recall that SBF had issued that very public statement that assets were fine and that the company had about $1 billion in cash. SBF now deleted all those tweets, including the one about the “competitor” and “false rumors.”

Then, out of nowhere, the websites of FTX and Alameda were pulled offline. Many questions continued to spin around Alameda’s leadership. It also emerged that the SEC had started an investigation a few months prior into FTX’s relationships with other companies led by Sam Bankman-Fried (And it seems there may have been many SBF-led companies.)

Also, on Nov. 9, Binance walked away from the deal. Their statement was jarring:

“As a result of corporate due diligence, as well as the latest news reports regarding mishandled customer funds and alleged U.S. agency investigations, we have decided that we will not pursue the potential acquisition of FTX.”

Binance said that it could not help FTX.

Now – the highlighted words (emphasis mine) in the statement – started to fuel the burning questions –and collapsed of Bitcoin to under $16,000. This was a critical turning point.

Last Friday, Fortune said that FTX is “a place full of conflicts of interest, nepotism, and lack of oversight.”

Where SBF and FTX Went Wrong

If we flashback to the summer when SBF was writing bailout checks for those hedge funds and exchanges, his hedge fund, Alameda Research, likely experienced significant losses.

Coinbase’s CEO Brian Armstrong noted that Alameda might have been underwater back then.

Alameda could have gone under in the summer.

That would have been an embarrassment, but it wouldn’t have sunk FTX.

It would have been like any other hedge fund that blows up during a significant period of volatility. It’s common in all public markets – and accredited investors know those risks.

But that’s not what happened.

Reports imply that SBF wouldn’t let Alameda Research go insolvent.

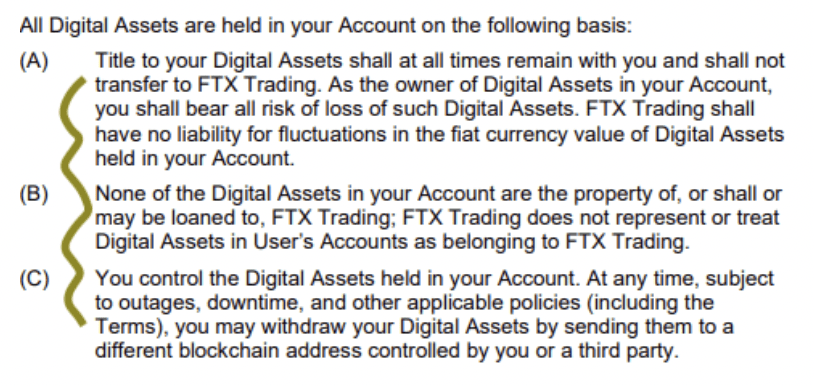

The Wall Street Journal notes that FTX loaned Alameda about $10 billion of the exchange’s customer funds. This was more than half of its $16 billion in customer assets.

That was directly against the company’s own terms of customer service.

This is not legal. You can’t use customer money to fund any operations. The money should sit in cold storage or outside operations at a one-to-one level. In addition to avoiding severe legal issues, securing client funds would stop a bank run. Coinbase does this.

But here’s how the Alameda loan worked, which was problematic:

Alameda – now underwater – borrowed several billion in customer funds from FTX and used the FTT token as collateral. They used their own token the backstop that loan.

“That’s the moment in my mind when he crossed the line into probably committing fraud,” Coinbase’s Armstrong said. “I think he lied to users, lied to investors… to prop up this thing.”

The total amount of money that Alameda misappropriated was at least $4 billion. But The Wall Street Journal reported that Alameda owed FTX about $10 billion. In addition, Alameda had about $1.5 billion in other non-FTX counterparty loans.

And that is where the “recent revelations that have come to light” statement by Binance from the previous week comes into play. The Binance team seems to have found out about Alameda. Binance announced plans to dump its position in the coin, dropping the price lower. At that point, Alameda’s collateral was insufficient to meet the loan.

All while the run on FTX kicked into high gear.

On Nov. 9, the stock market went into a deep sea of red as well – with technology stocks and anything linked to the cryptocurrency system taking a beating.

Markets were already on edge due to the growing concerns around the October Consumer Price Index (CPI) report. In addition to the problems at FTX, investors reported challenges at Coinbase. As a Coinbase user, I noticed the exchange struggled with temporary outages and difficulty signing into accounts.

When Coinbase finally returned online in the afternoon, crypto found its bottom that day.

Meanwhile, FTX told users not to deposit money into its system because it couldn’t even process withdrawals. That day, SBF was dealing with a significant hole in the balance sheet.

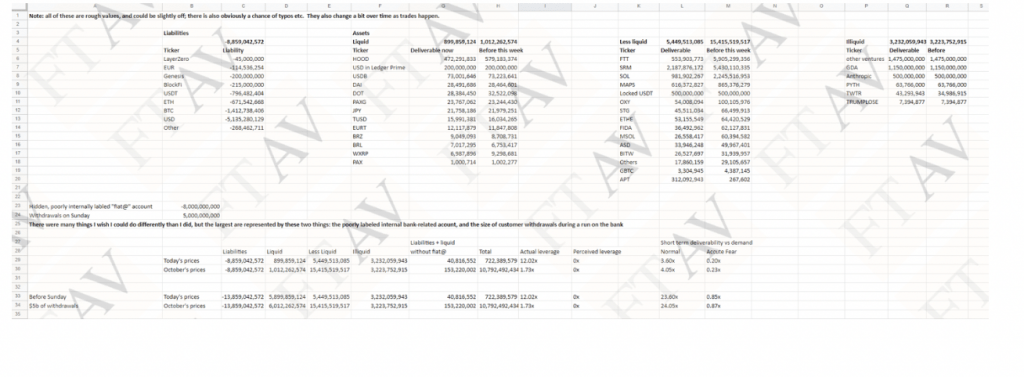

A rough estimate found its way to the Financial Times – and there is some SBF commentary.

Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong would say that he had spoken to SBF as the FTX founder tried to start raising emergency liquidity. That figure was at least $9 billion to stave off a bank run.

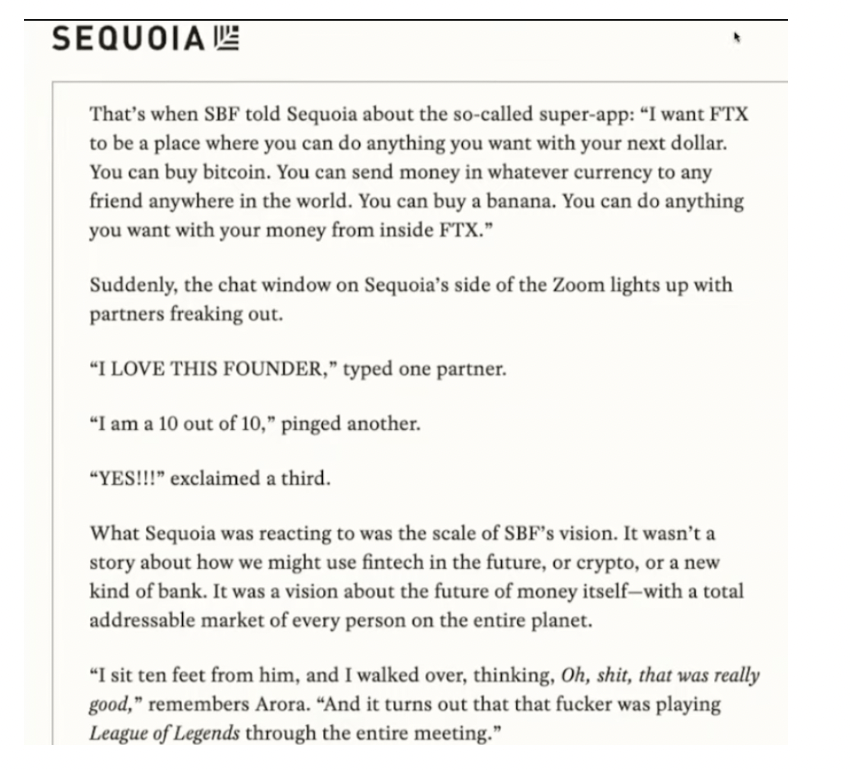

By Thursday – while the stock market was surging on the surprise CPI number – Sequoia Capital released a statement. It had lost about $213 million. It marked down the entire investment. Many people questioned if Sequoia had done its diligence.

FTX would soon declare bankruptcy in the United States. A court must review all the assets to determine if anything is valuable. They’ll sell distressed assets at auction, and then whatever funds are uncovered will be distributed to investors who lost money from FTX.

By Nov. 12, rumors emerged that SBF had flown to Argentina. But reports in the Bahamas noted that both SBF and his co-founder Gary Wang were “under supervision” by the local authorities. SBF finished the week with a series of Tweets in which he said he “f—ed up.”

He claimed he should have been more transparent. He said his hands were tied because of the Binance deal, which is a convenient excuse. “I’m sorry,’” he said. “That’s the biggest thing.”

Really? Is that the “biggest” thing?

Now Let’s Discuss How We Got Here

I’ve covered the cryptocurrency markets at a broader level since 2015 – back during the second wave of the price surge and ultimate crash in December 2017 and early 2018.

At the time, the industry was still young – and was hammered by various hacks and big questions for retail investors actively speculating in a widely unregulated market.

Does anyone still remember Mt. Gox – the hack in 2014 – that jacked about 740,000 BTC?

In 2017, there was wild speculation. People were buying up Bitcoin on their credit cards. They were purchasing assets in offshore crypto exchanges with outrageous security risks.

Back then – it feels like two decades ago – the big names in the crypto space were Barry Silbert, the Winklevoss Brothers, and Alex Machinsky, whose Celsius Network collapsed sensationally this year.

I interviewed Tyler Winklevoss in 2015. It was an intelligent conversation about the viability of money – and the future ecosystem of Bitcoin. It wasn’t a dive at all into “token economics.”

That conversation emerged two years later – as the token explosion was underway.

I met with the members of the Celsius Network back then at the 2019 SALT Conference.

I was supposed to do a full front-page interview with their executive team. But by the time I finished the interview, I felt that project was more of a house of cards.

I didn’t run that interview. I largely didn’t understand what they even did.

I didn’t dig deeper into the project’s validity or why Celsius’ collapse was inevitable. (Of course, Bloomberg reported in September that non-other than FTX was exploring a bid for the assets of recently collapsed Celsius).

For about a year, I stopped paying attention to cryptocurrency, and COVID profoundly changed the market.

I bought Bitcoin at the low in March 2020. And just speculated because the Fed had sky-dropped $5 trillion. All these assets – with questionable values from the beginning – especially the tokens – were exploding in value. It was clear a financial bubble…

I sold way earlier than the all-time high. That made me upset a little. But it’s better than buying in at $69,000 and holding on for dear life down to $15,500 this year.

The narrative had suddenly shifted in 2021 that prices would remain elevated because – institutional investors were entering the arena.

I couldn’t buy completely into this because of a straightforward question.

And that question remains the reason for my detachment.

I have never really understood a key trait of cryptocurrency as an asset class.

It all comes down to that one question.

No one has ever answered this question in a way that satisfied my cravings enough that I’d run to invest heavily in cryptocurrency as anything more than a speculative momentum asset. Here it is:

“How do cryptocurrency and blockchain create wealth?”

This isn’t a philosophical question. It’s an economic one.

I fundamentally do not believe these technologies create wealth.

Only one person – Anthony Scaramucci – offered a rational answer on Bitcoin – stating that the nature of its finite supply and global inflation – made it an interesting alternative currency. (There will only be 19 million Bitcoins ever in existence.)

But that’s not what I’m getting at.

I ask the legitimate question based on the differences between “wealth” and “abundance.”

In the basic theory, blockchain is an incredibly deflationary technology that creates “abundance” by streamlining processes, eliminating back-office operations, and accelerating creative destruction across supply chains and workforces. I’m not interested in how blockchain makes the world a better place. I’m focused on the deflationary efficiency gains.

There are also a variety of negative externalities ranging from imposed storage costs to outright energy costs related to mining Bitcoin and other assets.

People kept telling me that the tokens would create wealth because you had to buy the token to use a specific blockchain protocol for development and usage. If, for example, you want to use the blockchain on Solana, you need to purchase SOL tokens for development. It’s a customer capture. You’re exchanging dollars for these tokens, and speculators are trying to make a bunch of money on them in the hopes that demand increases for the tokens based on blockchain usage.

But in most cases, the supply of these coins isn’t “finite.”

Take Solana –a Web 3.0 protocol that believes it could replace the Nasdaq one day.

“Solana doesn’t have a max supply but an inflation mechanism. Solana is an inflationary token whose supply increases at a predetermined rate. By contrast, deflationary tokens, like Bitcoin, have a capped supply and are meant to be burned —eliminated out of circulation, potentially helping them increase their value.”

If that “customer capture” is such a brilliant business model – I’d buy Dave and Buster’s (PLAY) stock and call it a day. On the surface, this practice is like going to Chuck E Cheese and playing the games there. The restaurant has an alternative currency you must buy if you want to play Skeeball. The same goes for Dave and Busters. It would be best to use their “native currency” to play the games and exchange dollars for them.

Of course, with SOL, you could sell unused tokens on a cryptocurrency exchange where other parties are involved. You can’t do the same with Chuck E Cheese tokens – although you can sell a bunch on eBay (at a discount).

But in each case – if the restaurants go out of business or the cryptocurrency protocols or exchanges collapse, all those Fun Bucks go to zero. And that’s remained my key risk concern dating back a few years before all this tokenization became mainstream.

I’d been around long enough – back in 2017 – to hear the promise of projects like Siacoin and Dentacoin (one for decentralized computer storage that had massive questions about security and the other a cryptocurrency for dental payments). Both were stupid… and I lost some money on both. I foolishly was also trading on a foreign exchange with security risks.

So, I got pulled back into also this in 2021. We learned that institutional investors were coming online. In a post-COVID world, where crypto-asset prices were surging, the story went that Sam Bankman Fried was helping to legitimize cryptocurrency – and that we would witness a dramatic shift. Institutions would put these investments on their balance sheets.

And that’s where the next serious question for me emerged.

The promise of these tokens and projects was the lack of a centralized authority.

Decentralization was a theoretical world where transactions didn’t require third parties. Developers, artists, creatives, and customers could engage in specific transactions on these blockchains without having a company like Google, Apple, or Amazon take a cut.

But when it came to the exchange itself – where people would need to buy the assets to engage in those transactions elsewhere … it wasn’t decentralized at all.

With FTX, the decentralized goal of all these projects ironically ended up on a centralized exchange – enabling all the same problems that are risks linked to centralization…

- Hacking.

- Corruption.

- Fraud.

- Opaqueness.

No one really wanted to talk about that. It was always casually dismissed.

So, I just returned to asking how cryptocurrency creates wealth…

I asked this question all year. It was the critical point that I asked during the Money Morning LIVE! Summit in Chicago. It was a question that I asked while appearing on Fintech TV.

It was a question I asked many managers while attending the inaugural FTX-Salt Conference in April 2022. There was just one person to whom I never got to ask that question.

Sam Bankman Fried.

Mickey Mouse and The Fro

I met Sam Bankman Fried in the Bahamas for a few minutes.

It was all very unassuming. He was dressed in a Mickey Mouse shirt, half-tucked, and looked more like a fraternity brother who woke up at 1 p.m. than a billionaire technology executive.

I posted up most of the non-conference hours at the Sportsbook bar. I didn’t attend a meeting of venture capitalists on a yacht. I wasn’t at the VIP parties. I did pester Cathie Wood (American investor and the founder, CEO and CIO of Ark Invest, an investment management firm) about why she was buying stocks in companies where none of their executives were purchasing the stocks.

I spent most of my time measuring how significant this movement was.

But the only question I received more than “Who do you write for?” was, “Did you get to meet or interview Sam?”

I’ve never been starstruck. People are people. Some have anxiety. Some have egos. Some don’t mathematically calculate the improbability of all basic life happening. Some are too engrossed in power. Some make mistakes. But everyone is human.

SBF seemed down-to-earth.

He was nervous when he talked in public. He certainly didn’t dress to impress. He wore a grey tee shirt, cargo shorts, and Asics when interviewing Tom Brady and public officials.

That said, the persona didn’t match the attendees’ Hollywood treatment of him.

Sam’s staff revered him. His PR team couldn’t accommodate interviews. Asking for two minutes to get a quote from SBF was like calling on a Friday night and asking for a table for two at Dorsia — the fictitious restaurant in American Psycho that Patrick Bateman’s character is obsessed with.

Fund managers talked about him in a semi-deity manner. This felt more than anything like a giant birthday party for him.

He also got to interview Bill Clinton and Tony Blair – off the record – at the event.

Yet, for all the pomp, the headliners like Tom Brady and Tony Blair, an odd cloud did hang over this event.

Some people there were asking questions about the stability of Solana’s protocol. And Solana was a major sponsor at the event. I have a pair of their futuristic sunglasses from a swag bag.

For the broad market, performance was bad for the year. Bitcoin – fueled by $5 trillion in cheap money and plenty more in government stimulus – had climbed the previous year from $32,000 in January 2021 to $69,000 in November 2021.

By April 2022, it was down about 33% for the year (it’s off 64.8% in 2022).

Such performance was written off – at the time. The experience – what FTX was bringing by inviting so many people to the Bahamas – was wrapped in a very altruistic element often mocked in the TV show Silicon Valley about “Making the World a Better Place.”

“Your presence here,” said the event’s first speaker, “allows you to join some visionary leaders, big thinkers, bold idea generators, and disruptors who want to create a better world.”

I asked someone in venture capital – after we’d spent the day talking about the explicit need for financial education around this sector – “Have you ever felt like any of this is an illusion?”

That person suggested that the question wasn’t worth exploring. And perhaps inappropriate.

The event focus of FTX was the opportunity ahead to change the world – and never the risks.

If I could go back there, I’d have asked harder questions. I asked a very prominent fund manager – on-air – what excited him the most about cryptocurrency in the future.

He answered that one day you’d be able to go to dinner, use your phone, and pay in Manhattan using Bitcoin – before stating something about it being decentralized and not having to use a bank.

There are two critical things in this answer that I wish I’d challenged. You can see my face on the screen – turning my head a little, about to do so. But I didn’t… and that’s on me.

First, you can already pay for your dinner with Apple Pay. You can already pay for dinner in a different global currency (with exchange rates) through TransferWise or American Express.

Second, it’s evident that all the talk about decentralization is essentially an illusion.

Was FTX going to centralize everything and then give all that power back to the people one day by enabling a decentralized world? Based on the trajectory, it doesn’t appear so.

Why did FTX fail?

On another level, because of the inherent risks linked to centralization that I listed above.

The world’s only real decentralized payment exchange is barter (no government, no instrument). The next closest is physical cash in hand –even that money is centralized.

Now, I wouldn’t say that FTX was an illusion.

And I wouldn’t call this a Lehman Brothers moment… or a Charles Ponzi scheme.

It had a mix of Enron accounting shenanigans, a few chapters from Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay, the rockstar elements of the Fyre Festival’s implosion, and the 2011 saga where MF Global misallocated customer funds to paper over losses from risky trading behaviors.

MF Global was comparatively a $700 million misappropriation of capital.

And that was done by Jon Corzine, a former Democratic Senator, and CEO of Goldman Sachs.

Corzine never went to prison. Instead, he paid a $5 million fine and lost his CFTC registrations.

I question if SBF does go to prison over this. Roughly $40 million in political donations to one political party can buy some goodwill – and we’ve watched people like Jon Corzine walk. SBF’s parents were highly connected fundraisers in the political world as well. It just reeks.

Maybe I’m just too pessimistic about Washington.

But let’s dig into a few other critical elements.

What Was SBF Thinking?

Hindsight is 20/20.

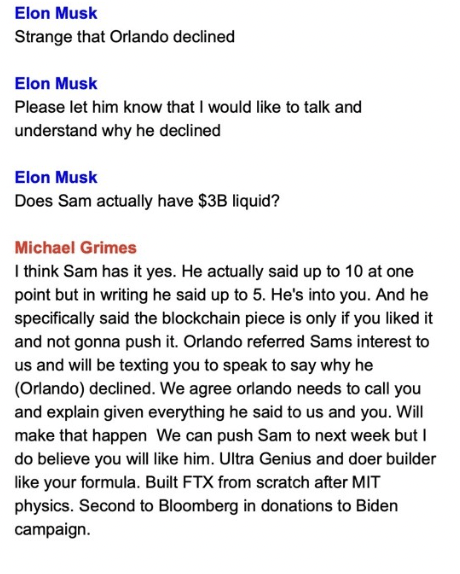

The interviews are starting to show another side to the situation. Anthony Scaramucci took a more lawyerly tone on CNBC this week. Elon Musk didn’t pull any punches and claimed that SBF wanted to help buy Twitter and add payment functionality. Musk said his BS detector went up because he couldn’t understand one thing. He even asked his banker Michael Grimes: “Does SBF actually have $3 billion liquid” capital? Here is the exchange (see right).

So where was SBF getting all this money?

What was SBF thinking? What motivated him?

Time will tell that story. It might have been altruism. It might have been a crime.

It could have been a desire to build this political and financial empire – a long game of chess in a world of influence, political favoring, and power-brokering.

That said – I think it’s critical to revisit the world of yield farming.

Remember when I said that SBF once described yield farming in a way that resembled a Ponzi scheme?

In April 2022, SBF joined the Odd Lots podcast to explain decentralized finance (DeFi).

The podcast came out a week after the FTX conference in the Bahamas.

What came next raised red flags for many people, myself included.

To start his analogy on Defi, SBF asked listeners to “imagine a box.”

“You start with a company that builds a box,” he said.

Then a marketing team will try to sell this box to investors as a protocol that will change the world. I told you; altruism is a potent tool in venture capital.

When you put established currencies into this box or protocol, it creates an IOU. It’s not a liquid system. It’s, by default – a promise of gains based on what comes next.

With the box or protocol constructed, crypto engineers will create and issue a token.

Here is where the problem with “token” economics starts.

First, the new crypto token – it’s a kind of voting mechanism. It provides the holders a say in what happens with the protocol in the future. That alone is worth a lot of perceived value because an investor wants to have that say. While it’s not monetary, it’s behavioral value.

But remember that SBF described it all as “a box.”

The company can give away this token, sell it, raise money in Silicon Valley for this token, and use it with enough mass acceptance as collateral for loans and other forms of funding. As more people recognize the box as a legitimate source of value, a herd perception of the value of that project starts to emerge. Is that all fantasy?

How much is the box actually worth? And how much are the tokens worth? It’s subjective.

“I acknowledge that it’s not clear that this thing should have a market cap, but empirically I claim it would have a market cap,” SBF said on the podcast. He claims it has a market cap.

And that’s where the legitimacy issue accelerated. SBF – again, it’s incredible that he went down this path – says that this box starts to generate higher returns from the increasing levels of attention from new participants.

Speculators follow these projects and try to buy the token for $1 and sell it for $2, which increases the perceived value of this box. And again – this is nothing new – this is the subject of Charles Mackays’ Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds in 1841.

With more people paying attention and more speculation, the value of the box and its tokens starts to rise. And if the box-maker keeps the number of tokens small, the value can surge.

At this point, the host Matt Levine called the entire thing “cynical.”

SBF replied that the entire thing came down to the perception of the buyers and sellers.

The question is how a token like this can then start to yield 20% returns out of nothing.

The whole thing involves off-chain activity where one person trades Bitcoin for these tokens, then leverages them for other off-chain activity. The chain of custody is difficult to track. And when people ask for their money back in the original transaction, that Bitcoin or other forms of capital can’t be delivered. One person is trying to generate 5% – while the person promising 5% is out there looking for 13% and keeping the difference – and that person ends up taking the original investment and tries to lever up to deliver 20% and keep the difference from 13%.

It’s a house of cards. It all starts with the original tokens that have questionable value.

But remember – the marketers were influencing public perception about the box from the start. And even though there are questions about whether this box and its tokens have any intrinsic value, FTX was in the business of selling these tokens on its exchange.

This year, we’ve seen a variety of these tokens collapse.

We had several stablecoins implode. The death of Luna helped drag down those companies’ receiving bailouts. And several coins with zero value – hello, Dogecoin, and Shiba Inu (and those are the “safe for work” names – have been wildly speculative assets on every major exchange over the last few years.

When this entire saga unfolds, the natural question is why FTX, Coinbase, and Binance would create a market for these worthless assets.

You can hide behind “free market” dialogue all you want. You can say, “If we don’t do it transparently, investors will buy it from somewhere else….”

But it’s very hard not to compare Token Economics… and the Rumanian Money Box scam of Victor Lustig in the early 20th century.

Money doesn’t just come from nowhere.

And the sheer number of companies and investments from Alameda and FTX is crazy.

What Were Others Thinking of Sam?

Now… “What were people thinking of Sam?” – as people wanted a piece of the rockstar.

He was the smartest guy in the room.

People wanted to believe. They didn’t ask questions. They complete due diligence.

When it came to money – his money – it perplexed many how FTX was such a cash machine.

Looking back, it didn’t seem plausible that FTX’s exchange was throwing off so much cash to justify SBF’s ability to toss bailout and marketing money around.

Was it all the balance sheet of Alameda? That will ultimately be a key revelation.

I am reminded of a conversation I had with Tom Sosnoff, a founder of TastyTrade, just a few months ago. At the time, we discussed the viability of political prediction markets like PredictIt and gambling sites like DraftKings.

Tom argued that there isn’t enough liquidity and demand in those markets – evident in the wide spreads. How could the companies in those arenas kick off lots of cash flow, become sustainable, and justify significant valuations?

Brian Armstrong, the CEO of Coinbase, finally spoke out this week about Sam. He said that he didn’t expect this event to happen. Yet, in hindsight, he reflected on warning sighs.

In 2021, Coinbase did $7 billion in Revenue and $4 billion in EBITDA. Those are great numbers for a company going public out of the box.

Meanwhile, FTX reported $1 billion in revenue in 2021, and its net income was $388 million.

Again, FTX did $1 billion in revenue – and SBF had more liquidity than its public rival.

SBF had bought up 8% of Robinhood. He bailed out Voyager and BlockFi. FTX took a 30% stake in SkyBridge Capital, its partner, in the FTX-SALT Crypto Bahamas conference.

SBF donated a ton of money to politicians. It had a big deal with the Miami Heat (FTX Arena). The logo was on every umpire’s uniform two weeks ago during the World Series.

Armstrong couldn’t figure out where the money came from. The only explanation was that Alameda was “printing cash.”

Yet, while SBF was bailing out these companies, and cryptocurrency values were imploding, common sense states that Alameda likely wasn’t solvent. FTX successfully raised $920 million earlier this year in Series B1 and Series C, but the effort to raise capital right now?

In an emergency crunch, SBF needed $9 billion in the middle of a cratering market, and the Federal Reserve raised interest rates from 0% to 3.75% over nine months…

It became a house of cards.

Armstrong suggests that SBF lied during public interviews about the state of FTX.

There aren’t many other people who did.

But the most vocal was Marc Cohodes, a short seller who appeared with Keith McCullough’s show on Hedgeye in October 2022. Cohodes couldn’t figure out the source of SBF’s fortune.

“When anyone tries to pin SBF on where he made his money, you can’t get a cogent answer,” Cohodes said. “And in his trade, you needed real money, upfront, in the place on this country crypto arbitrage to make real money. And simple things – as ‘who financed you – because you didn’t have the money.”

Cohodes went on a further rant about Gary Wang, who also served as a board member of Sequoia Capital. Allegedly, Cohodes says Wang is the CTO of FTX. “Nobody can find shit on Gary Wang,” he said. “There’s no picture of Gary Wang.”

Then, Cohodes argues that SBF had bailed out known alleged scammers in Voyager Digital and Three Arrows – yet “Cartoon Network” – his preferred term for CNBC – had dubbed SBF the “JPMorgan of Cryptocurrency.”

“He’s not the JPMorgan of crypto because he can’t sit there, look at you straight in the face, and explain anything,” Cohodes said.

He continued: “Nothing here fits. Everything reads like it’s a complete scam. This thing is dirty and rotten to the core.”

Whether this was all a grand delusion, the madness of crowds, or we ultimately discover fraud, this week will be very interesting as the onion continues to peel.

As it does – it will be important to ask another thing about Alameda.

I wonder a lot about the business practices of Alameda.

You see, SBF had worked at Jane Street Capital – a prop fund that engages in payment for order flow. He was an intern and worked there while he was in college. That’s important.

And – prop funds like Citadel, Susquehanna, Virtu, and Wolverine – pay for order flow. They can legally front-run order flow if they know what’s being bought and sold in volumes.

Was Alameda doing the same – eyeing order flow on FTX? Were they trading that information?

The answer is – yes.

Cryptocurrency compliance giant Argus announced that Alameda had insight into which new tokens would join the FTX exchange. They would begin to amass coins before the public listings and then sell them at a profit.

From March 2021 to the beginning of this year – Alameda held at least $60 million in 18 coins that were eventually listed on the exchange.

“What we see is they’ve basically almost always in the month leading up to it bought into a position that they previously didn’t,” Argus co-founder Omar Amjad, told the Wall Street Journal in November. “It’s quite clear there’s something in the market telling them they should be buying things that they previously hadn’t.”

But that begs the question – how did a group of math geniuses fail so hard at basic margin trading, monetary policy, and accounting?

What Were Fund Managers Thinking?

At various cryptocurrency conferences, you’d meet allocators and private equity funds – and everyone wanted a piece of the action – because the story is incredible on the surface.

Crypto is incredibly disruptive. It’s altruistic (making the world a better place).

The institutions are showing up and will offer “legitimization” for many projects.

Who doesn’t want to surround themselves with influential players? The next stop for a few people I met in the Bahamas was… the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, the following week.

The list of firms and people who lost a lot of money on FTX is extensive.

It wasn’t just venturing capital companies like Paradigm, Sequoia, and Temasek.

It counted Iconiq Capital as an investor. That company manages money for Jack Dorsey.

Forbes suggested that Tom Brady lost up to $45 million, while his ex-wife Giselle Bundchen lost $25 million. Both were brand ambassadors for FTX. Bundchen signed on as the company’s Environmental and Social Initiatives Advisor.

SBF and Bundchen also appeared in New York Times ads that said, “I’m in on crypto because I want to make the biggest impact for good.”

Again, altruism was a massive force.

Other outlets have posted way more substantial loss projections for Brady and Bundchen.

They’ll be fine, but this does trickle down to the middle class. The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP) sank $95 million into FTX. This article below quotes the CEO of the OTPP talking about how low the risk was associated with FTX.

Whoops. But OTPP wasn’t the only teachers’ pension fund to lose much money.

The fundamental question is how did so many people abandon risk management practices?

Someone in the risk department must do their job – even if they’re fired for doing so. These are supposed to be the stewards of retirement capital, family office money, and so much other wealth. A few people I’ve spoken to have called for those fund managers to be fired.

I won’t speak to this. I’ll instead offer two other points.

First, no one did their diligence because they wanted to believe and because of herd mentality. This isn’t so complex. It’s basic human behavior, and it’s why there are so many books about wild speculative events dating back to the Roman Empire wheat markets.

If you’re a fund manager, and you’re not in a specific type of investment – while a competitor is making 40% a year on that investment – the question is, “Why aren’t you doing this?”

That creates a compounding effect. And that’s how we’ve ended up with situations over the last few years involving venture capital and later investment disasters in WeWork, Theranos, Uber, and many other companies where diligence was just tossed out the window.

But this all speaks to a broader issue.

It begs a bigger question from the insane market rally of 2020 and 2021. In a world fueled by trillions of cheap dollars (out of thin air) and zero-percent interest rates – where should people have put money last year?

The Federal Reserve dropped $5 trillion from the sky, and valuations went insane. The world of Silicon Valley was overwhelmed with startups seeking money, a blistering auction on talent, and less time to complete due diligence.

I can imagine a former startup client of mine saying this in 2020 to a pension fund manager …

“You’re not interested in tossing $85 million into my second round at a $5 billion valuation? Then, screw you, pension fund manager… because when I come back in nine months, the valuation will be $16 billion, and I’ve already got four people calling me back in the next three hours with interest in investing. You’ll have to answer why you passed directly to your investment partners… If we hit, you’ll forever be the guy who passed on the next Facebook, Google, or Amazon.”

Fear of missing out (FOMO) isn’t just a retail phenomenon.

And there was a dramatic distortion of markets thanks to the Fed, and the outlandish valuation pops that transpired not just between 2020 and 2021 – but the entire market since 2008 when the central bank started pumping trillions of dollars into the system.

And if you think no one would talk like this to a fund manager, consider this revelation.

SBF pitched FTX to Chamath Palihapitiya and his Social+Capital Partnership during its Series B round, which produced an $18 billion valuation.

Chamath said this week that he didn’t understand the business. So, his team put together a short deck with recommendations for FTX. The proposals weren’t that earth-shattering.

- Form a Board of Directions.

- Create a dual-share structure that kept SBF in command.

- Warranties around related-party transactions.

The next day, a representative at FTX called Chamath’s team and said: “Go #@$% Yourself.”

Chamath thought they were just arrogant and confident – and maybe they’d created a “money-making machine” in the Bahamas. FTX could say this to Chamath – because – they had investors like Sequoia, Temasek, and Paradigm throwing money at them.

That deal round raised $900 million from 60 investors.

The Series B list included NEA, Coinbase Ventures, Willoughby Capital, Izzy Englander, Alan Howard, Vaneck, the Paul Tudor Jones family, Hudson River Trading, and Circle Financial.

These are all mighty names. And if I’m a smaller shop, I see Alan Howard or Hudson River Trading – and I assume that they can do far more diligence than I can because they have far more resources – and an excellent track record. Plus, they have Sequoia praising the founder.

“FTX is the high-quality, global crypto exchange the world needs,” Sequoia partner Alfred Lin said in a statement in June 2021 after investing in the Series B round. “Sam is the perfect founder to build this business, and the team’s execution is extraordinary.” See this:

It’s “industry” nature to suspend belief after seeing a partner at Sequoia go all-in like this…

But in the end, everyone assumed – with names like the ones above – that a firm like Sequoia did even a tiny amount of due diligence.

That herding effect is like everyone assuming that there will be someone to drive the sober bus home – but never asking if someone at the bar is sober or prepared to be sober.

It wouldn’t surprise me if half those names did less than three hours of diligence on FTX before writing a check.

What were Venture Capitalists Thinking?

Now, here’s where the story gets more interesting.

If we peel all this back – FTX wasn’t really selling cryptocurrency if there wasn’t a specific allocation to meet customer funds. FTX was selling IOUs if it was never matching assets one-for-one.

So long as everyone didn’t make a rush on the exchange, it would be fine. But FTX didn’t have enough capital to meet all customer demands when the rush on the exchange accelerated.

And that makes me question the fundamental nature of the tokens themselves. SBF and many other crypto startups created many tokens out of thin air. They wrote lines of code, went to a venture capital fund or a pension manager, and said, “Lend me $50 million, and I’ll give you this native token that people need to own to get benefits on our platform.”

What was it worth? Well, on the surface – the intrinsic value Is zero. You can’t use them anywhere else –like you can’t spend Dave and Buster’s bucks at McDonald’s.

But in a world of dreamers and “making the world a better place,” the ecosystem could be worth $32 billion – if enough people suddenly believe it. Someone in Washington needs to take a good look at the entire basis of token economics, which is insane to start, and “a cocaine-riddled stallion fleeing a burning forest” in a leveraged financial world.

The fact that these tokens are used as collateral is an issue that requires significant investigation – and stronger oversight. This practice creates graft.

You couldn’t do this anywhere else. You can’t run an alternative energy company, call Goldman Sachs and request $40 million because you’re “making the world a better place” – even if you’re building a way to reduce the carbon output of the economy. You can’t say that you have a magic box with wildly subjective valuations and get tens of millions of dollars.

If you’re raising money, there must be a deeper conversation about the business, how it makes revenue, and how it aims to profit. You must understand the bottom line and how you’re structuring the business. There must be projections of cash flow based on tangible assets, the formation of advisory boards, and a coherent corporate strategy that doesn’t involve a global network of loosely aligned subsidiaries.

And you can’t adequately collateralize hypothetical wish coins.

This is where there will be more problems ahead.

Remember how Matt Damon was looking down on Mars in Crypto.com commercials? Well that company has its own token as well. Cronos has all the same benefits as the FTT token – like lower trading fees and lending rewards. Since Saturday, November 12, the price of Cronos has declined by more than 25%.

This whole situation is systemic.

The tokenization of “industry X on the Blockchain” has become a significant driver of deal flow in Silicon Valley over the last few years. Several prominent firms are pushing this business model. Back in 2018, Keith Teare was promoting Venture Network Fund. This year, Antonio Hallak launched Illumina Capital – a token-only investment vehicle. It’s not bad that tokens are created and funded in rounds, but it requires a deeper regulatory reach. I can’t understand what any of these funds do.

If they can’t explain what they do in six sentences or less, regulators need to do it for them.

Chamath Palihapitiya alleges that large venture capital businesses have been educating teams on how to manufacture these tokens. He argues that there should be deeper investigations into those business practices – as there are still plenty of sites that host videos focused on this questionable business practice.

People need to ask questions because this will create a series of headaches around token economics – and the fundamental “wealth” that I still don’t believe crypto will make.

I don’t believe that FTX has destroyed the cryptocurrency industry.

But this is just the beginning of something much bigger. The token economy feels like a broad industry scam built on mass delusion and unsustainable financial practices. There is much more to investigate in this world.