The Hummingbird Project

Finance meets tech in a new thriller called The Hummingbird Project. Writer-director Kim Nguyen spins the tale of two youngish cousins who quit their jobs at a New York-based hedge fund that specializes in high- frequency trading to dig a 4-inch fiber-optic tunnel between the Kansas Electronic Exchange Data Center and the New York Stock Exchange servers in New Jersey.

They’re out to create a 1,000-mile straight line a few inches wide and six feet underground. They’ll have to pierce the Appalachians and traverse swamps, rivers, forests, cropland, pastures, and lots of citizens’ front and back yards. Why? To get rich by shaving a millisecond off the time it takes to get stock quotations.

That would make the cousins the first to know what the big players are buying and what they’re paying. Then their computer algorithms would help the cousins jump to the head of the line and make the right trades before their competitors.

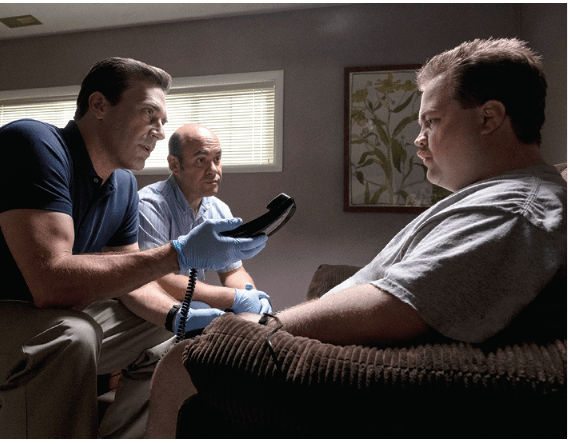

Both protagonists supposedly know why they’re seeking big-time wealth. Business-savvy Vincent (Jesse Eisenberg) tells a prospective investor of being knocked unconscious and having a vision of a shadowy man imploring him to “hold the line.” Until he builds the line, he won’t know what’s at the end of it, or so goes his phony- sounding spiel to a prospective investor. Vincent’s cousin and partner, tech savant Anton (Alexander Skarsgård), simply wants enough cash to hide out in a country house on a hill. There, Anton plans to spend his days with his wife, two kids, and lots of computer codes.

As a foil, the cousins have their former boss, Eva (Salma Hayek), who hurls profane insults at employees and titillates investors with tales of what she calls “nanosecond financial engineering.” When Vincent and Anton quit their jobs, Eva claims contractual ownership of the cousins’ ideas and warns them that they’re leaving empty-handed.

Threats aside, the cousins and their tunneling engineer, Mark (Michael Mando), soon dispatch 54 crews to dig along a line extending from the Great Plains through the Midwest and nearly to the East Coast. They’re simultaneously engaging countless landowners for the right to pass under properties. The race — always a handy dramatic element for a movie — is on.

As the heroes rush to finish the project before the money runs out, they encounter monumental encumbrances. Recalcitrant Amish farmers who plow with horses don’t want to help the world go faster by allowing right-of-way for a tiny tunnel beneath their land. The drill bits are no match for stubborn veins of granite lacing the mountains. No matter what, the team has to maintain the straightest possible line to avoid slowing the transfer of information.

At the same time, they’re racing to improve their coding enough to slice a millisecond off their roundtrip time or else the project won’t produce faster communications than the ever- improving competing methods.

Meanwhile, yet another race is taking shape. Back in Manhattan, Eva has her minions hard at work on a pulse-shaping algorithm that would enable microwave towers to send signals that make the roundtrip between Kansas and New Jersey in 14 milliseconds, which would beat the heroes’ time by a full two milliseconds.

Other complications arise, too, intensifying the race, raising the stakes and lowering the probability of success. The affair eventually becomes a matter of choosing a safe life or risking untimely death.

The movie’s not in the “based on a true story” Hollywood mold, but it was inspired by real-life headlines and non-fiction books. Montreal-born filmmaker Nguyen became fascinated with high-speed trading after reading Michael Lewis’ 2014 book Flash Boys:

A Wall Street Revolt.

Nguyen based the characters he created on speed-obsessed “quants.” They’re the physicists, engineers and mathematicians who have become financiers and now generate more than half of all U.S. stock trading. The film blends elements of a buddy picture and a road movie. It grazes the peripheries of finance, technology, science, avarice and dreams. It’s entertaining for most moviegoers, but experienced investors shouldn’t expect to come away with a deeper understanding of trading. — Ed McKinley