Ad Dollars Discover Podcasts

As podcasting shifts from free-form conversation to scripted narrative, pre-recorded ads are replacing “live” spots read by a host. What does it mean for revenues?

The podcasting industry is reshaping its approach to advertising in ways that parallel changes at album-oriented FM rock music stations in the 1970s. Instead of hosts reading every ad “live” in the middle of their programs, more spots are pre-recorded.

That’s the observation of Stuart Last, a former BBC radio executive who now heads Audioboom, a New York-based podcast company that distributes about 250 podcasts. He believes the shift toward “canned” commercials is occurring at least partly because podcasts themselves are becoming more scripted and less spontaneous.

“If we go back five years, probably 80% of podcasts were personality-driven with a host talking with guests in a studio—whether that be in a professional studio or home studio,” Last notes. “That was a pretty standard format.”

Those unscripted talk shows tended to last 45 minutes to an hour and a half and were produced weekly—frequently enough to connect brands with advertisers, Last says. “They were easy to monetize once they have a good audience because they don’t cost a lot to produce,” he continues.

Talk’s not cheap

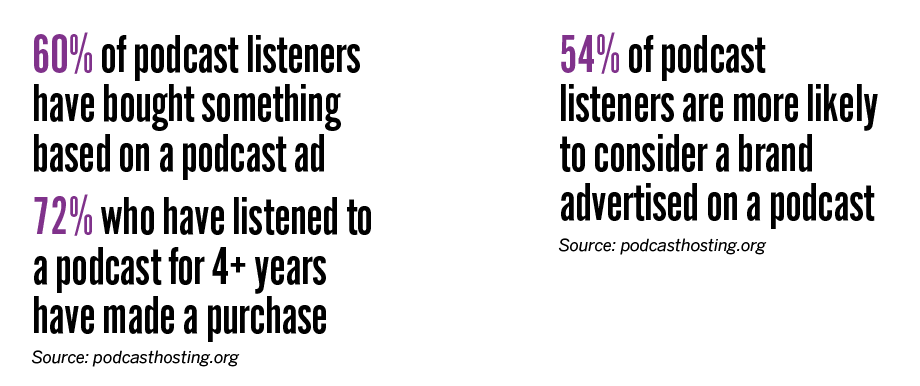

Small advertisers have been attracted to talk-show sponsorships because having the podcast personalities read the ads imbued the commercial messages with whatever prestige, expertise or star power the host had amassed with the audience.

“Those ads have always been sold and then delivered by the podcaster in the fabric of the show,” Last observes. “They’re kind of baked into the show. They’re in the voice of the podcast host.” So ads could get a boost from the host’s enthusiasm and connection with the audience.

That’s fine if potential advertisers are convinced they want their products or services aligned with the persona of the host. If ad buyers have their doubts, ad salespeople face challenges. “It’s been a heavy lift on the sales side, and it’s very reliant on the host of the show,” Last acknowledges.

That reluctance among advertisers persists even though many small or medium-sized businesses have gotten more than their money’s worth with podcast ads, according to Last. “I’ve seen some great conversion from the advertising that they do in podcasting,” he says of companies with limited ad budgets. “They have built their businesses on the back of podcasting.”

Moreover, the opinions of small advertisers are fading into irrelevance for the top tier of the podcast industry these days, as well-heeled large companies open their checkbooks and begin to make their presence felt in the industry.

Big money, lots of downloads

Spotify’s multiple nine-figure acquisitions of podcasts and podcast companies are detailed elsewhere in this issue of Luckbox, and so is Sirius XM’s expensive purchase of Stitcher. Those and other cash infusions are altering the upper echelons of the industry.

“Bigger media companies and bigger publishers have stepped into the space, and they’ve put more money into the development and the production of podcasts,” Last says. “So, the top-end podcasts sound a lot different than they did 10 years ago.”

The big money is separating the pros from the hobbyists, Last contends. Of the more than 1 million podcasts available, he estimates that about 30,000 qualify as major players capable of generating serious revenue.

“Beneath that, the other podcasts include a fantastic group of content creators, but it’s the enthusiast level or hobbyist level creators,” he says. “If you wanted to make a podcast out of your particular love of a certain genre of music or out of a wonderful sport that you are into, you could find a way to do that and you could find an audience that was into that.”

But an audience of modest size won’t suffice at the professional end of the podcast spectrum, Last contends. Powerful advertisers demand 100,000 downloads per episode, Last says.

Second-tier podcasts still qualify as professional if they net at least 40,000 downloads per episode, he continues. Podcasts in that category can maintain high production standards and still pique the interest of some advertisers.

For anyone with a podcast audience smaller than that, success is becoming increasingly elusive, Last believes. Five years ago a great podcast could become an organic hit, but a healthy marketing budget is becoming essential, he cautions.

Some fundamentals of the podcasts themselves are changing, too.

Limited longevity

While old-school, conversation-oriented podcasts could theoretically continue as long as the host lived, many of the new narrative-style offerings are designed for a limited lifespan. With scripted podcasts, a series might pursue a storytelling arc that runs eight to 12 episodes, Last says.

The shorter run can become more difficult to monetize because advertisers like established, long-running vehicles, Last says. But the trend toward such podcasts will continue, he predicts.

Meanwhile, podcast length is shrinking and frequency is increasing, he notes. For example, The Daily podcast from The New York Times lasts just 20 minutes but comes out five times a week. That enables it to present news instead relying upon the evergreen themes of older podcasts.

Some of the new formats could hamper ad sales, but that won’t slow the march of “progress.” Last views the situation as similar to what happened in FM radio when ad rates wound up in a race to bottom and ad frequency increased to compensate. Eventually, podcasting might not remain what he calls a “premium medium.”

Impending doom?

“You go from this great place we have today in podcasting, where only three minutes of every hour is advertising, and there’s going to be a lot of pressure to go where FM radio is, which is 12 minutes—at least—of advertising per hour,” Last warns, adding that “it wouldn’t be a good thing for podcasting.”

An alternative lies in going the way of cable television by charging for subscriptions. Perhaps 2% to 5% of a podcast’s listeners have the loyalty of super-fans and would donate $10 a month to help sustain the enterprise, Last says, noting that paid subscribers usually get perks that aren’t available to non-paying listeners.

Some podcasters at the upper end of the download spectrum could also skirt the advertising issue by concentrating on the audience engagement that podcasting provides. Cable TV networks, for example, use podcasts to convince viewers to watch their movies or series.

Still, podcasters should attract the ads they need by simply making the best of their medium. Last puts it this way: “We’re still creating that premium product that can sell that premium piece of advertising.”

Big Audioboom Dynamite

Audioboom got its start in London in 2009 by providing services for radio and podcasting. About four years ago, the company began transforming itself into a content distributor and ad sales business in “the premium end of the podcast industry,” says CEO Stuart Last.

These days, Audioboom operates globally from its headquarters in New York and bills itself as the world’s largest independent podcast company. Of its 250 podcasts, it produces 25 of them in-house through Audioboom Originals.

The shift to podcasting is working. The company’s lineup of podcasts is averaging more than 8.5 million weekly downloads, according to The U.S. Podcast Report issued in July by Triton Podcast Metrics.

“So we’ve kind of left the radio piece behind,” says Last, who worked as an executive for BBC radio for 12 years before joining Audioboom. Judging by that comment about taking up podcasting and forsaking radio, he’s apparently a master of the British art of understatement.