Disney vs. Netflix: The Battle for Big Media

A clear favorite is emerging as Disney and Netflix co-opt each other’s business models in a battle for entertainment dollars

The harder Netflix (NFLX) and Disney (DIS) battle each other, the more they look alike. Netflix got its start by distributing entertainment content and then began producing it, while Disney has done the opposite. The resulting rivalry appears likely to turn vicious this year and may end with a single victor.

It’s a clash that’s been a long time in the making. In 1923, brothers Walt and Roy O. Disney began creating silent films that combined live action and animation. (No, Mickey’s Steamboat Willie cartoon wasn’t their first effort.) As the technology changed, the company produced talkies and then television shows. Now, it wants to copy the Netflix business model and begin streaming content.

Netflix, founded in 1997 by Reed Hasting and Marc Randolph, found its niche in mailing rental DVDs back and forth with customers, and it later moved into video streaming. Realizing Netflix couldn’t remain a middleman forever, management began running original content six years ago with the release of the company’s first series, House of Cards.

Wildfire growth

Disney and Netflix have both been growing prodigiously. Netflix has gone from market capitalization of less than $10 billion in 2013 to about $160 billion today and in the process assumed its rightful place among the giants of the entertainment industry. Meanwhile, venerable-but-vibrant Disney recently completed the $71 billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox.

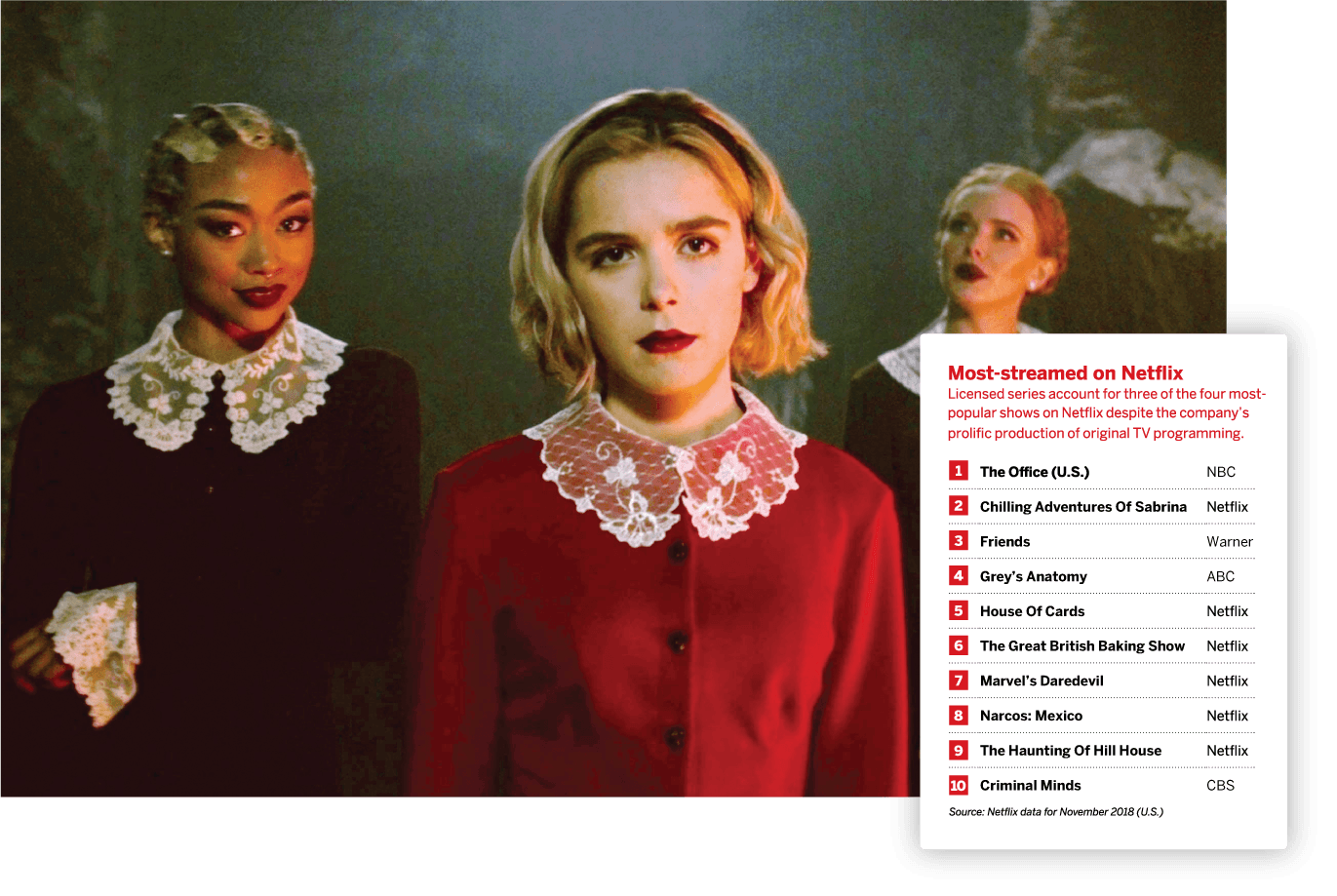

So the battle lines have been drawn, but it may come as a surprise that licensed content still accounts for nearly two-thirds of Netflix viewing hours despite the company’s burgeoning inventory of original programming. Netflix still relies heavily on classic television shows like The Office, Friends and Grey’s Anatomy, not to mention its dependence on a catalog of Hollywood, independent and foreign films. As Netflix’s rivals begin launching their own streaming services, they’ll cancel the licenses, making Netflix less attractive to consumers just as the competition heats up.

But Netflix has been preparing for the loss of its licensed content for years. As the company’s chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, said on the company’s fourth-quarter earnings call: “Our early investment in doing original content… was betting that…there would come a day when the studios and networks may opt not to license us content in favor of maybe creating their own services.”

Still, creating world-class TV shows and movies requires Herculean effort, and the audience’s viewing habits die hard. As you can see in “Most-streamed on Netflix,” right, licensed television hits accounted for three of the top four streaming series on Netflix for November 2018.

Netflix has grown from market capitalization of less than $10 billion in 2013 to about $160 billion today. Meanwhile, Disney recently completed the $71 billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox

The most-popular classic TV shows aren’t cheap. Netflix reportedly paid $100 million to keep Friends on its service for 2019, more than triple its previous licensing fee of $30 million. While that’s a hefty price tag for a series that’s been off the air for almost 15 years, it’s still watched more than the vast majority of Netflix’s new releases.

Unfortunately for Netflix, it won’t be able to keep Friends forever. Warner Media plans to launch a streaming service later this year. And the potential trouble for Netflix doesn’t end there. Disney, which owns Grey’s Anatomy, will also launch its streaming service in 2019, while NBC Universal will likely want to reclaim the rights to The Office when it launches its own service in 2020.

So what happens to Netflix when it loses those shows? It gets worse. It’s not just that licensed shows accounted for 63% of viewing hours in November 2018. As recently as 2017, more than 40% of Netflix subscribers watched licensed content almost exclusively. Even if original programs have cut that number in half over the past year and a half, that still leaves one in five domestic Netflix subscribers (nearly 12 million people) who almost never engage with the roughly 700 original TV shows the company produced last year.

In fact, the sheer number of Netflix originals might be making the licensed content problem even worse. Research suggests that when consumers are presented with an overwhelming array of content, they tend to retreat to the programs that are most familiar to them.

The Giant Keeps Growing

As Netflix spends on originals to try to counteract the loss of licensed content, Disney has expanded its content library with the 21st Century Fox acquisition.

Consider what Disney has gained:

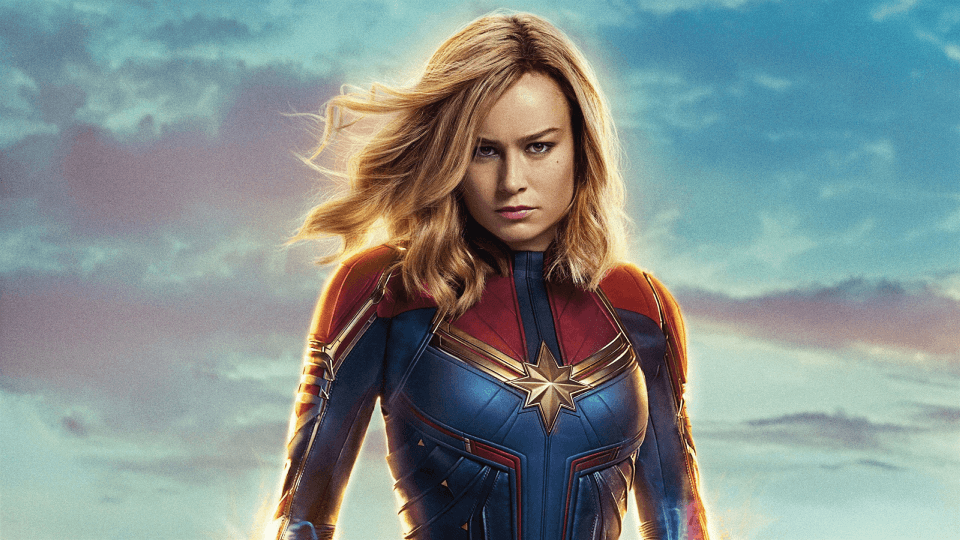

- Avatar, the highest-grossing movie of all time, with a rumored four sequels in the offing

- X-Men and Deadpool, which round out the Marvel Cinematic Universe

- Smaller, but still-successful franchises like Ice Age and Planet of the Apes

- A large number of critically acclaimed TV series from the FX network that can meaningfully contribute to a potential streaming service

- A controlling stake in Hulu, which is currently growing at a faster rate than Netflix

While most acquisitions destroy value, Disney appears to be among a handful of companies that can reliably create value through acquisitions. Few companies can match Disney for brand value, creative expertise or breadth of content monetization channels. Those assets enable the company to buy up beloved intellectual property (including Pixar, Marvel and Lucas- Film), churn out multiple blockbuster films, and then aggressively monetize the success of those movies through theme park attractions, licensed toys and spin-off TV series.

Disney has acquired beloved intellectual property created at Fox, Pixar, Marvel and LucasFilm and could monetize those movies through theme park attractions, licensed toys and spin-off TV series

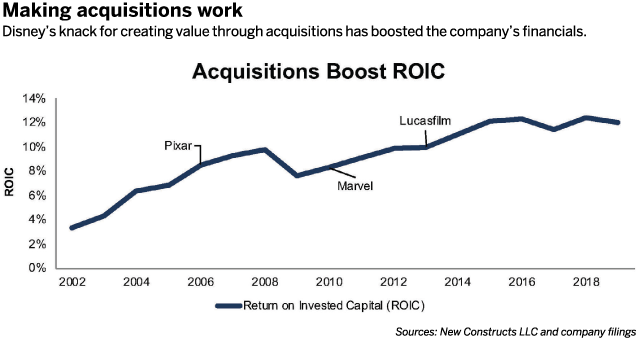

Those abilities have helped Disney significantly improve its profitability during the past 15 years, and they represent the company’s most significant advantages in the content wars with Netflix. Disney’s long-term track record of success at creating value through acquisitions has helped improve return on invested capital (ROIC) from 7% in 2005, the year before it bought Pixar, to 12% TTM (the trailing 12 months). (See “Making acquisitions work,” below.)

Disney projects the Fox acquisition will add $3.6 billion in profits and cost synergies, which equates to a 5% ROIC. However, Disney’s focus on efficient capital allocation, along with a record of growth and profitability, should give investors confidence that the long-term ROIC of that will climb even higher.

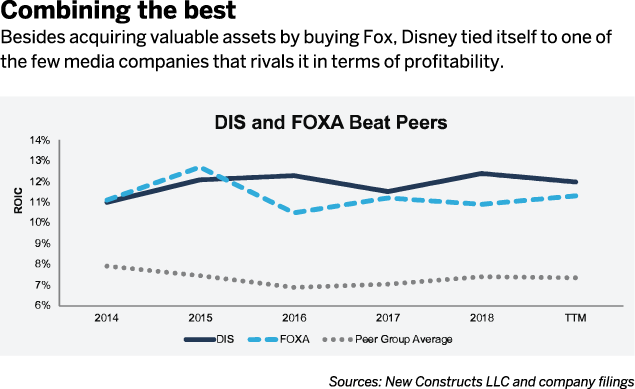

Besides acquiring valuable assets in the Fox deal, Disney will partner with one of the few media companies that has managed to rival it in terms of profitability in recent years. Since 2014, both Disney and Fox have consistently earned a higher ROIC than their peers. (See “Combining the best,” right.)

By acquiring Fox, Disney gained great content while absorbing the company that poses the most competition. The new Disney+ service now owns critically acclaimed FX shows such as Atlanta, The Americans and Fargo to complement its exist- ing, more family-friendly content. Disney will also be licensing third-party content for its streaming service, which will enable it to build out an impressive content library even as Netflix’s library shrinks.

Add the fact that Netflix is raising its price again this year, from $11 per month to $13 per month, and plenty of subscribers may contemplate switching. Disney CEO Bob Iger has promised to price Disney+ below Netflix, so the service could prove an attractive alternative.

In addition, Disney already has a rapidly growing streaming service in Hulu, which recently topped 25 million subscribers, up 50% from a year ago. Disney plans to expand Hulu internationally, which could drive significant growth.

ESPN+ also has been a modest success for Disney. The sports streaming service, which offers events and shows that aren’t broadcast on its cable networks, topped two million subscribers in its first year. Many analysts were skeptical that the second-tier content offerings would find a following, but the service’s quick growth suggests otherwise.

Each of these offerings helps Disney segment its audience and maximize the value of its content.

The Netflix dilemma

Disney’s approach stands in stark contrast to Netflix, which seems to want its service to be all things to all people. Netflix’s investment in original content was supposed to give it the ability to dominate a variety of TV and movie genres. However, the company seems reluctant to acknowledge that its original content strategy has not achieved that goal. When Ted Sarandos, Netflix chief content officer, acknowledged that Netflix’s original content strategy aimed to help offset the loss of licensed content, Sarandos also said: “The vast majority of the content that is watched on Netflix are our original content brands.”

As the statistics show, however, that answer’s simply untrue. Sure enough, Hastings, the company CEO, quickly stepped in to correct Sarandos. “In unscripted (reality TV) now, it’s our first category,” he said. “Where a majority of the viewing is a branded original, in the other categories we’re climbing – not yet at a majority, but on track for it.”

Netflix spent $13 billion on content last year, with 85% of new spending earmarked for original programming. For that much money, they should be more than just “on track” for originals to dominate viewing in every category.

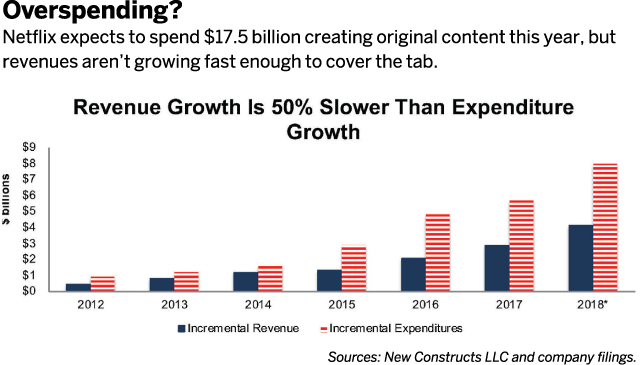

Rather than acknowledge the limitations of the strategy, however, Netflix appears determined to throw more money at the problem. The company hasn’t released a specific content budget for 2019, but management expects content costs to continue growing at a rate similar to its previous trajectory, which would put the company on pace to spend $17.5 billion this year. But revenues aren’t growing fast enough to cover rising expenses, as can be seen in “Overspending?”.

As a result of rising content costs, Netflix has been forced to take on debt at increasingly higher costs. Since 2014, Netflix has raised more than $9.8 billion (6% of market cap) in debt. Since 2017, its cost of debt has risen by 275 basis points to 6.375%. If the bond market loses its willingness to fund Netflix’s content spending, the company’s streaming strategy could go up in smoke.

Netflix microbubble?

The Netflix stock microbubble may burst in 2019 if the credit market tightens or patrons migrate to Disney+. Netflix appears significantly overvalued because of unrealistic expectations for profit growth and market share gains.

Conversely, Disney looks like a winner. Its valuation is depressed because of overblown fears that Netflix will hurt the profitability of its existing business. If the Netflix business model proves unsustainable, and Disney shows it can compete successfully in the streaming business, a great deal of the investor capital currently allocated to Netflix should flow to Disney instead.

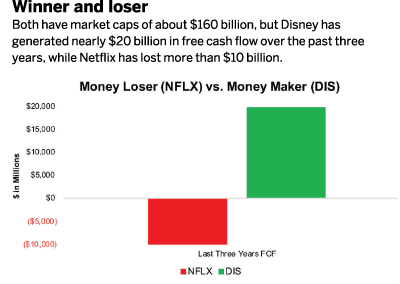

Both have market caps of $160 billion, but much different free cash flow (FCF). Disney has generated nearly $20 billion in FCF during the past three years, while Netflix has lost more than $10 billion. (See “Winner and loser,” page)

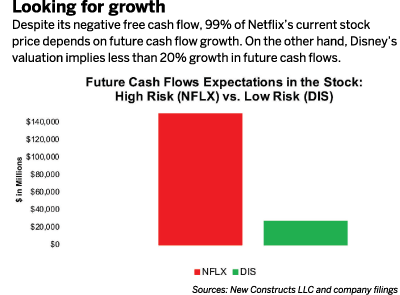

As you can see in “Looking for growth,” page 36, despite its negative free cash flow, 99% of Netflix’s current stock price depends on future cash flow growth. On the other hand, Disney’s valuation implies less than 20% growth in future cash flows.

Despite its history of negative free cash flow, Netflix is valued as though it will become as profitable as Disney. Meanwhile, Disney is valued as though its profits will barely grow – despite a history of profit growth.

The Content War

Given their respective valuations, the market apparently expects Netflix to win the upcoming conflict with Disney. However, the market is overrating Netflix’s temporary advantages while underrating Disney’s more durable competitive strategy.

Netflix has two key advantages in its quest to become a global media giant:

- First-mover advantage: Netflix was the first to build a major streaming platform, and that’s helped it reach nearly 150 million subscribers. However, the first-mover advantage doesn’t last long.

- Content budget: Netflix’s decision to spend billions on content has helped the company drive rapid growth in the short-term. However, it’s content binge isn’t sustainable. At some point, Netflix will have to stop funding its content library through debt markets, and it will then face the unenviable choice of raising prices or scaling back spending, either of which will hurt its subscriber numbers.

On the other hand, Disney enjoys three durable advantages that should help it remain the world’s largest media company for decades to come:

- Timeless brands: Consumers in the current age of “Peak TV” tend to flock to the familiar. While Netflix spends billions on new content, Disney can fall back on its wide array of timeless brands that produce reliable blockbusters year after year.

- Platform value: Netflix has only a single stream of revenue, limiting its ability to monetize content. Disney, on the other hand, can monetize content through movies, cruises, licensed toys and, soon, its own streaming platforms.

With Netflix facing increased competition and the loss of licensed content over the next year – while it simultaneously raises the prices it charges – 2019 is shaping up as the year that Netflix’s temporary advantages dry up, while the market begins to appreciate the long-term success of Disney’s business model.

David Trainer is CEO of New Constructs, an independent equity research firm that uses machine learning and natural language processing to parse corporate filings and to model economic earnings. Sam McBride is an investment analyst at New Constructs. @newconstructs