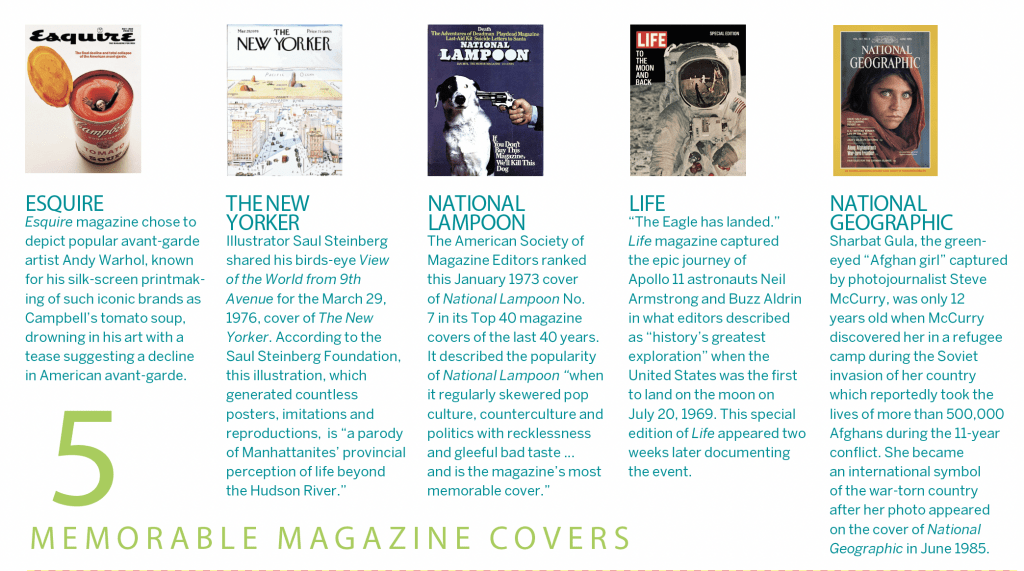

The New Look of Magazines

Publishers are determined to keep committing ink to paper

Familiar magazines are moving online at a startling pace, but that doesn’t mean print publications will disappear from America’s nightstands, coffee tables or waiting rooms.

In fact, print is making something of a comeback on the strength of four trends: one-off editions, brand ownership, tightly focused content and a switch from timeliness to timelessness.

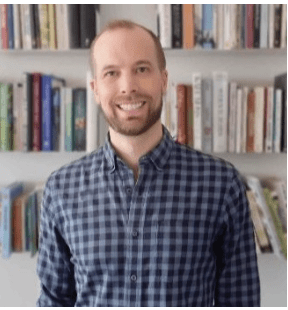

The resurgence means magazines will continue to shape and reflect popular culture but in new ways, according to Samir Husni, who founded the Magazine Innovation Center at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi, and earned the nickname

“Mr. Magazine.”

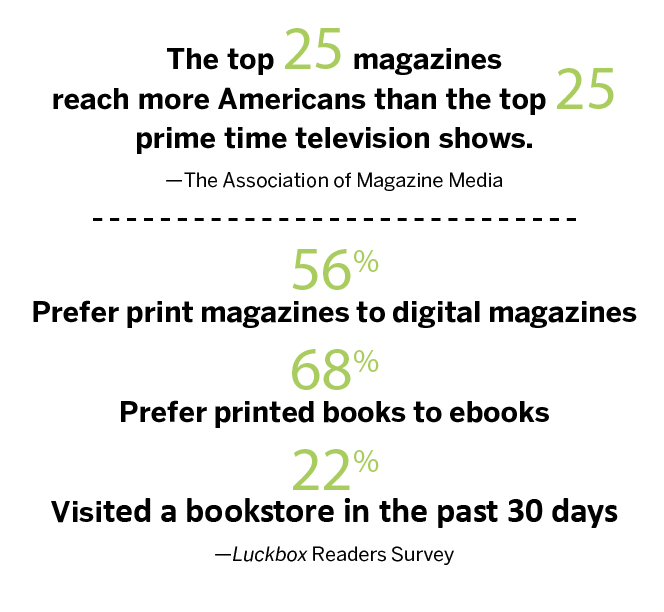

Besides, readers simply aren’t ready to give up what they view as the endearing qualities of print, said Rita Cohen, president and CEO of a trade group called MPA—The Association of Magazine Media.

“Consumers love the experience and feel of print magazines,” Cohen maintained. “They are a relaxation moment—a break from screen time. The tactile feel of the paper is enjoyed by millions.”

Some of that love is directed these days toward single-issue publications, said Krifka Steffey, Barnes & Noble’s director of merchandise, newsstand and media. Industry insiders used to call them SIPs for short but now refer to them as bookazines, she noted.

Let’s take a look at them.

One-off publications

The portmanteau “bookazine” comes from mashing up “book” and “magazine.” It fits because bookazines combine aspects of both.

At first glance, bookazines look a lot like the magazines next to them on newsstand shelves or supermarket racks. But differences become apparent upon closer examination.

Unlike magazines that appear weekly, monthly, quarterly or annually, most bookazines are published once and then disappear forever. Only a few extremely popular bookazines warrant a sequel or reprints.

Bookazines are usually focused on a single subject—like Princess Diana, the secret life of cats, the golden age of Vikings or the illustrated story of Jesus—instead of offering a magazine’s usual string of diverse articles.

Advertising, the lifeblood of magazines, seldom appears in bookazines. Instead, bookazine publishers and retailers make money from a relatively high purchase price. The extra expense is justified, Husni maintained, with slightly better paper stock, high editorial standards, stunning photography, and the appeal of a single specific topic. At Barnes & Noble, domestically published bookazines sell for $9.99 to $14.99, and imported versions go for as much as $20, Steffey said.

Bookazines often use the name of a venerated magazine as part of the title. Examples include National Geographic—Everest and Better Homes and Gardens—Secrets of Getting Organized. Those trusted names encourage shoppers to associate bookazines with magazines.

Bookazines are pushing aside magazines on the shelves at Barnes & Noble, Steffey said, noting they already take about 40% of the newsstand space in the chain. Other newsstands devote as much as 70% of the space to them, according to Husni.

Despite the attention bookazines are attracting, they aren’t the only publications vying for space with traditional magazines. Periodicals owned by brands have been a factor in magazine publishing for well over a century.

Brand-related magazines

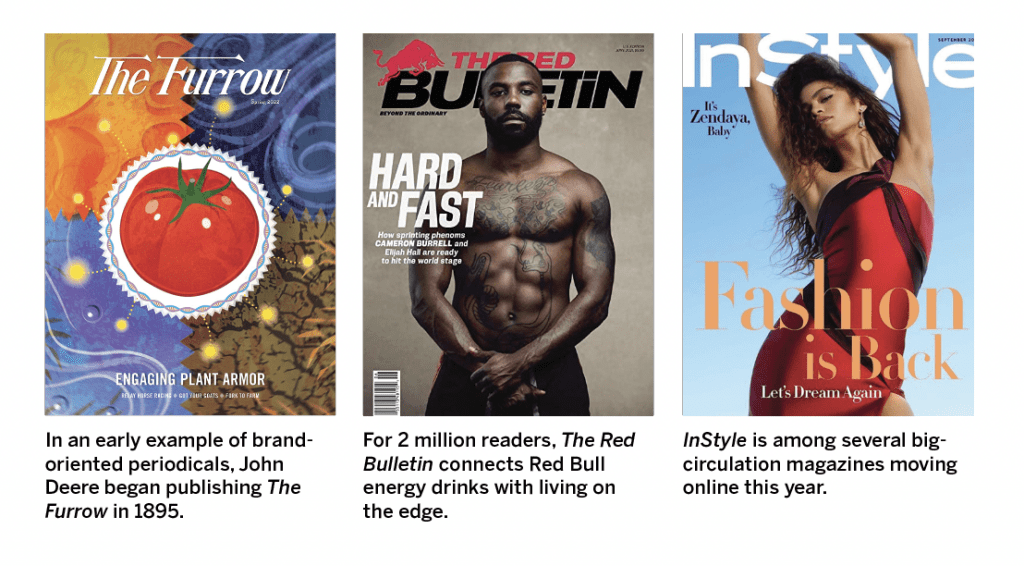

It’s widely believed in publishing that the John Deere farm implement manufacturer launched the first periodical tied to a brand. The company introduced The Furrow in1895, and it’s still publishing it today.

But other brand-owned periodicals outdate that farm magazine, including one distributed by the American Tobacco Co. in the 1880s, said Steven Lomazow, a New Jersey neurosurgeon who’s collected 83,000 magazines and written several books on magazines. (See “For the love of print.”)

To illustrate the enormity of the branded phenomenon, Lomazow described obscure examples, like a 1943 issue of Squeal, a magazine brought to the American public by Hormel, which was then a meat packing company. It has since expanded into other types of food processing and now calls its magazine Inside Hormel Foods.

Name a subject and Lomazow can probably produce a brand-related magazine that covers it. Examples from the past include The Highway Traveler from Greyhound Bus Lines and TV magazines distributed by television manufacturers.

These days, brand magazines are often considered “content marketing,” said Joe Pulizzi, who founded the Content Marketing Institute and publishes a magazine called

Chief Content Officer.

Companies can promote their products by publishing a magazine that associates their brand with anything interesting or exciting, Pulizzi said.

“I receive Mazda’s Zoom magazine because they want me to buy another Mazda after I’m done with the one I have,” he noted. “If you have a loyalty goal … a magazine might be the way to go.”

Publishing a print magazine can prove costly, he said, because they require a database, postal fees, content, design and production. But many companies publish their own print periodicals just the same.

“There are thousands of brand magazines that you never hear about because they are delivered to a specific person at a specific place and are not found on a newsstand or for sale online,” Pulizzi said.

Successful examples include LEGO Life, which launched in 1987 as Brick Kicks, he said. The energy drink Red Bull publishes The Red Bulletin magazine, a general interest print periodical that reaches 2 million readers.

The Red Bulletin and Airbnb Magazine are among the brand magazines on the shelves of Barnes & Noble, and Steffy characterized their sales as “OK.” But she cited two brand magazines as extremely strong sellers: Sift, from King Arthur Flour, and Magnolia Journal, which follows the home renovations of TV personalities Chip and Joanna Gaines.

Despite the huge variety of topics they cover, brand magazines and bookazines share a few traits.

Something in common

Brand magazines and bookazines offer a tighter focus than traditional magazines. That’s one of the reasons bookazines exist, but it’s also true of many of the brand magazines edited to expand a company’s clientele.

Both tend to offer “evergreen” content that’s relevant longer than many of the articles in traditional magazines. They’re ceding breaking news coverage to the internet, where immediacy rules.

But those qualities—specialization and timelessness—are also beginning to appear in traditional magazines that are becoming more like bookazines. Take the cases of O, The Oprah Magazine and Coastal Living.

Those titles are switching from monthly to quarterly and improving the quality of their paper stock, said Steffey. The switch makes sense for the industry, she asserted.

“In both of those instances, even though I’m getting fewer issues, the price point is higher. So, for the retailer, it’s almost a wash,” she said. “For the publisher, it’s a lot more advantageous because the financials on a bookazine look a lot better than pushing subscriber rates and managing all the advertisers.”

Such changes may have become inevitable in a world transformed by the internet.

Traditional magazines

“The large-circulation magazines are disappearing,” Husni lamented. “You have companies killing one magazine after the other because they want to focus on digital.”

More than 2 million subscribers weren’t enough to save the print version of Shape magazine. Publishing giant Dotdash Meredith moved the 40-year-old periodical online last December because the business model just wasn’t working—too many advertisers prefer to deliver their messages via the internet instead of on paper.

Shape was hardly alone. Magazines that have ceased to exist as print publications this year include Eating Well, Entertainment Weekly, Health, InStyle, Parents, People en Espanol, Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, Popular Science, Air & Space Smithsonian, and ARTnews.

Their 19th-century business model of selling magazines for a low price to build circulation and then selling ads based on guaranteeing a certain number of subscribers was failing in the digital era, several sources agreed.

However, the movement to take traditional magazines online opens the field for bookazines and brand magazines to fill the vacuum, said Pulizzi, the advocate of content marketing.

What’s more, some industry leaders insisted the era of advertising hasn’t ended for print magazines. “We expect print magazines containing advertising to be around for a long time,” said Cohen of the publisher’s association.

Perhaps print can accommodate all of the trends percolating in the industry, she suggested.

“There is most definitely room for various types of magazine business models to coexist because each offers a unique way to reach consumers,” Cohen maintained.

“Bookazines provide a platform for evergreen magazine content to thrive and find new audiences,” she continued. “Content marketing can stand alone or be included as a section of an existing magazine. Ad-based revenue models can coexist with subscriber- and reader-based revenue models.”

For the Love of print

New Jersey neurosurgeon Steven Lomazow has amassed a collection of more than 83,000 magazines. They line the walls of nearly every room in his house. Some date back to the 1700s. One’s worth $47,500.

It all began 50 years ago when he walked into a Chicago bookstore during his first year in med school. A collector by nature, he had decided to start accumulating medical books.

Lomazow noticed that the bookseller was misrepresenting the store’s copy of the Vol. 1, No. 2 issue of Look magazine as the first issue. He asked about Vol. 1, No. 1 (pictured left), and was told no one had it.

“I was hooked,” Lomazow recalled. A magazine collector was born.

Fifteen years later, he traded an issue of The Saturday Evening Post signed by Norman Rockwell for the coveted original issue of Look. Since then, he’s landed a second one.