AMC Entertainment: Time to Buy a Ticket

This theater sector analyst and trader projects a happy ending

This month, when luckbox was seeking an authoritative voice on the movie theater sector, the search led to fund manager Andrew Cowen, who’s traded theater stocks for more than 15 years. In mid-2017, when theater stocks were under heavy selling pressure, Cowen was brimming with optimism for Regal Entertainment Group, which has since been acquired. He made the following statement in a June 2017 article, Rumors of the Movie Theater Industry’s Death are Highly Exaggerated.

“RGC is the second largest domestic movie theater operator by screen count. Regal (and the movie theater industry, in general) has been a favorite and poorly chosen company among the short-selling community… This down move is an opportunity, particularly in light of a good box office year with a decent looking slate for 2018 as well.”

RGC was trading at $20.75 in mid-2017. Six months later, Cineworld Group (CINE) acquired RGC for $23 a share.

Investors harbor a dark skepticism of movie theater chains in general, but their distrust of AMC Theatres seems especially deep. AMC’s stock has lost more than half its value since the company acquired a series of competitors in late 2016 and early 2017. The stock remains under pressure despite excellent and relatively steady cash flows and financial results that beat expectations for fourth quarter and full year 2018.

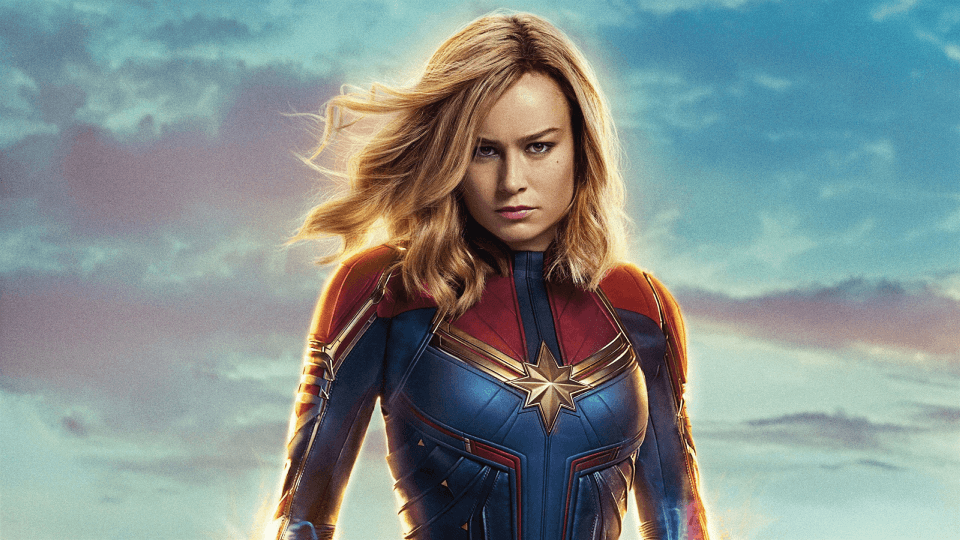

AMC has many detractors with 20% short interest. The short thesis is based on two main legs – one old and one new. Neither is correct. The old short thesis holds that Americans don’t go to the movies anymore. There’s supposedly too much competition for their eyeballs from the likes of Netflix, Hulu and Amazon Prime.

The competition thesis simply rehashes a concern that surfaces anytime new technology rolls out. Similar arguments were made over the years against movies with the advent of television, cable television with movie channels, home gaming systems, the VCR, pay per view, the DVD and now streaming services. With all of that innovation, some might think movie theaters are going the way of the buggy whip. In reality, U.S. box office receipts set a record in 2018, and it was one of three record years in the past four. What other “dying” industry just posted its best revenue year ever?

I struggle to think of another industry that is ‘dying’ but also just posted its best revenue year ever.

Still, critics point out that 2018 U.S. movie attendance – the number of people sitting in the seats – decreased 17% from its 2002 peak. But they’re cherry picking the data. The years between 2002 and 2004 were extremely good years for movie attendance. In the mid ‘90s, movie attendance was about the same as now. Meanwhile, ticket prices have climbed more than 100% in the past 20 years. During the past 10 years, attendance has hovered around 1.3 billion, while ticket prices have increased around 20%.

Besides missing the big picture on ticket sales, skeptics are missing the growth in concessions. Ticket sales have a margin of about 50% because of splits with the studios. Concessions have 85% margin. Theaters have aggressively upgraded their concession offerings to include alcohol in many locations. As a result, AMC earned more than $5 in concessions per patron in the U.S. last year, up from $3.95 in 2013 for more than a 30% increase.

With those healthy revenue lines and steady margins, it’s difficult to view AMC as part of a dying breed. Yet a significant number of investors manage to do exactly that.

While some misread movie industry trends in general, others misread a specific new program at AMC. AMC began offering a subscription service called A-List in June. Depending upon where they lived, initial subscribers paid $19.95 to $23.95 per month to see up to three movies per week.

Bearish analysts immediately jumped on a worst-case scenario: A regular moviegoer who sees three movies per week, or 12 per month, at a full price of say $9 per ticket, would suddenly pay only $20-$24. AMC would be giving up $108 per month in revenue. Worse yet, those obsessive patrons would actually cost AMC money because the chain would have to reimburse studios as though those customers were paying full fair. So AMC would be paying $54 to the studios (half of $108) and only collecting $20-$24.

In reality, however, the A-List works exceedingly well for AMC. The average subscriber was going to the movies 2.8 times per month as of AMC’s Q4 2018 earnings release. At worst, AMC is sacrificing only a few dollars of ticket revenue if those customers were normally going 2.8 times per month and paying full fare. However, AMC said on a recent earnings call that the average A-List member was going to the movies only once every two months and bringing full-fare customers with them. In other words, the program is meaningfully increasing attendance. What’s more, the new attendees are spending on high-margin concessions.

The A-List could exit 2019 adding 5% to AMC’s EBITDA, and it is doing so by providing steady, predictable revenue – unlike the box office, which depends heavily upon what movie is showing.

The data contradicts negative views of the movie theater business and of AMC in particular. Similar flawed arguments were made against Regal Cinemas for years. Regal shareholders were bought out at generous terms by Cineworld Group in 2017. Cineworld, in turn, is doing extremely well with those assets. AMC is close to the low end of its valuation range since it became public. This low multiple does not mesh with the company’s current state or its trajectory.

Andrew Cowen is head of Equities at Community Capital Management, an investment advisor. He’s co-portfolio manager of funds that include Community Capital Alternative Income, Quaker Small-Mid Cap Impact Value and Quaker Impact Strategic Growth.