Hikes at the European Central Bank

The reliably timid ECB is hinting at raises in interest rates

Something shocking happened in early February—the European Central Bank opened the door to rate hikes later this year. For a central bank that hasn’t tightened policy since 2011, that came as a surprise.

While the ECB represents the world’s largest economy, it’s also relatively new and has hiked rates in only 20 times in its entire existence, with just two since the global financial collapse.

Timing hasn’t been on the bank’s side. It was started in 1999 and was soon thrown into the dot.com bust. And when the property bubble burst in 2008, the Euro-zone plunged into a negative spiral that it addressed with years of low rates and accommodation.

The ECB even tried its hand as a trend-setter, but that quickly went awry. Jean Claude Trichet, then president of the ECB, attempted to hike rates in 2011. After a 25 basis point adjustment in April, Trichet and the ECB tightened again in July.

That’s been widely considered the start of the European debt collapse, when the PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) teetered on the brink of debt devastation. It even led some to question the long-term viability of the European Union.

The problem for the ECB remains a structural issue, and that’s the challenge for a single central bank to control both rate policy and currency stability for an extremely varied economic bloc. It’s impossible to compare the German economy with the Greek economy as apples-to-apples.

For a long time that was a strength. Diversity was an economic driver because during times of economic duress the stronger economies in northern Europe with strong currencies imported goods from southern Europe, where currencies (and in-turn, exports) were often cheaper.

But as soon as much of the continent subscribed to the same monetary policy, the ECB faced the task of finding a healthy balance for policy that was neither too restrictive nor too accommodating for a wide range of 19 nations operating under a single economic umbrella.

This disorientation may still be too much to bear. The story of the euro and the European Union is still being written, but in the short 22-year history of “the single currency,” there’s been far more panic than harmony. That’s what brings us to the next stop in the story.

The ECB

Europe’s central bank has had only two rate hikes in the past twelve years, but both blew up in its face and now it seems rightfully timid about tightening policy.

The plot thickens because the ECB has been in the midst of a monetary experiment, and no one knows the repercussions. It began a negative rate policy in June 2014 that remains in place today. The ECB cut deposit rates again in 2015, 2016 and 2019 to arrive at a negative rate of 50 basis points, which has remained through the pandemic.

The rationale was that negative rates would encourage investment and discourage savers. That wasn’t wildly popular, especially with the remarkable differences between southern and northern European economies.

But as inflation has started to take hold in the Euro-zone, the ECB appears to be positioning for a possible rate hike later this year. That would be similar to recent shifts in the U.K. and the U.S., but the posturing at the ECB has been met with disbelief. After all, it’s a central bank that’s built a pattern of dovishness, and now it’s saying something that it’s rarely said—that it may hike rates in the near-term.

Ukraine and the EU

While early February was all about the ECB, the focus shifted east later in the month as Russia lined the Ukrainian border with troops and artillery. Shortly after the close of the Winter Olympics, Russian forces invaded their neighbor and brought yet type of risk to the European Union. That made it even less likely the bank will adjust rates later this year.

While higher rates of inflation are likely because of rising energy costs, growth will also slow, at which point the ECB faces the same difficult decision as the Federal Reserve in the late ’70s. Hike rates to stem inflation while allowing growth to plummet in the process? Or keep rates accommodating to promote growth at the risk of higher inflation?

While that’s never an easy decision, history shows the ECB will likely have a bias toward the passive side, letting inflation run hot while keeping rates relatively low and policy somewhat accommodating.

This also exposes European markets to continued divergence with global trading partners, particularly the U.S., as the Fed prepares to hike rates for the first time since the start of the pandemic.

That could slow growth in the Euro-zone and reduce corporate profits, which were already lagging behind those of many other major economies. It could expose European equities as a point of vulnerability from higher rates of inflation to go along with a greater degree of uncertainty in and around the block.

Trading this theme

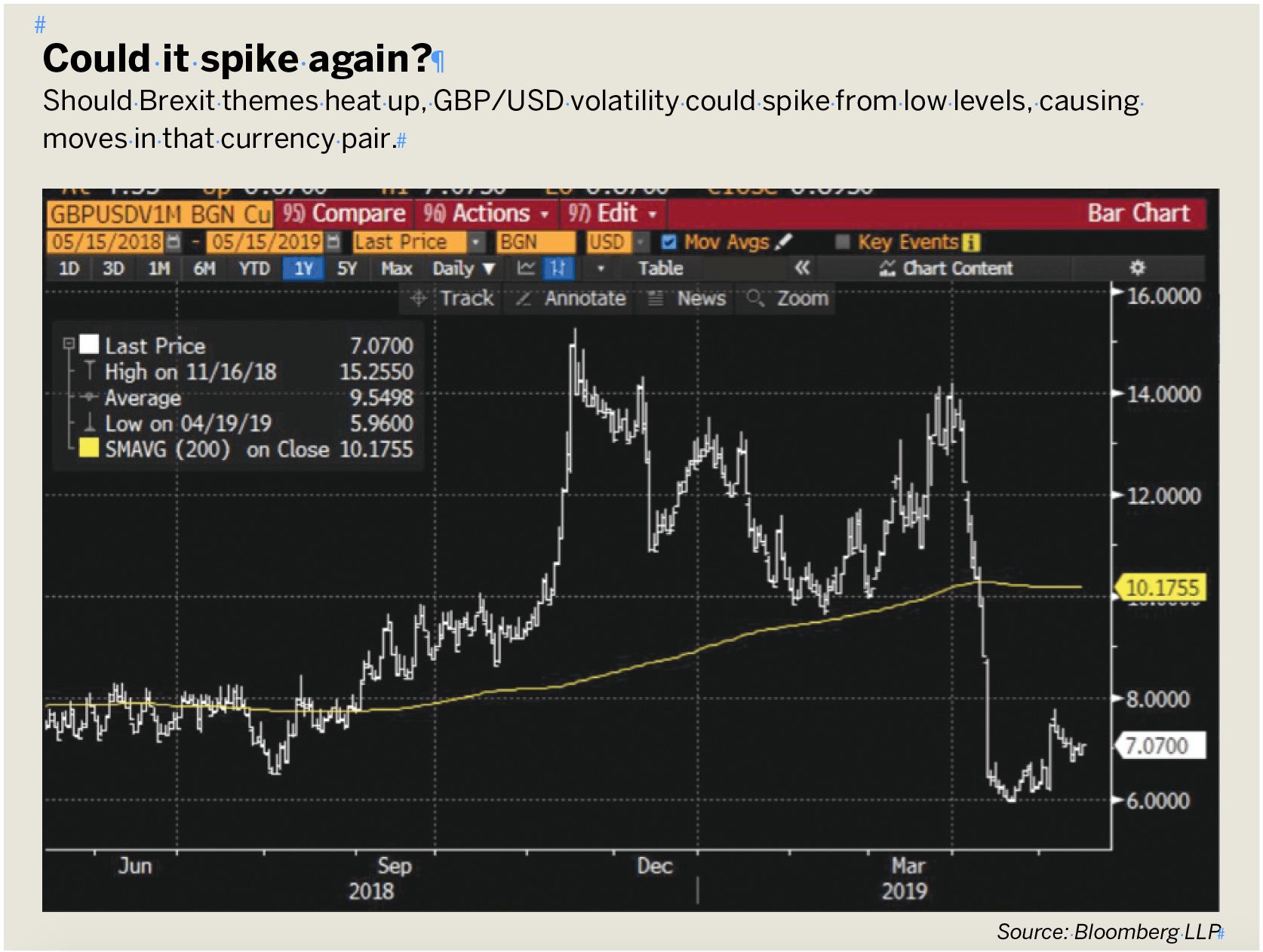

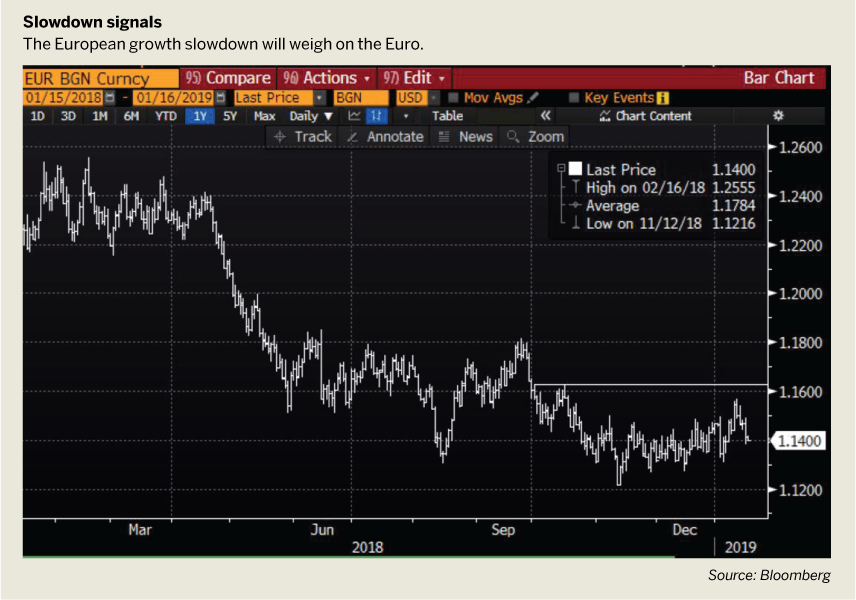

The first trading theme around the ECB is the EUR/USD currency pair. It’s the most popular pair in the FX market as it represents the world’s two largest economies.

While EUR/USD was prone to trends and large moves shortly after it came into inception and during the European debt collapse, the past five years have largely been mean-reverting, with price action moving deeper and deeper into a symmetrical wedge pattern.

These can be difficult to work with for directional approaches as the formation is essentially only showing compression, but it does highlight the potential for a big move once there’s some element of resolution.

For directional biases, let’s default to fundamentals and expect the Fed to push tighter policy further and longer than the ECB, even if the European Central Bank does post a “lift off” from negative rates later this year.

This bearish bias on the pair also incorporates the progressively lower-highs that have shown in EUR/USD since the financial collapse. That exposed the frailties of the Euro, and matters haven’t improved since then, especially as the possibility of political turmoil continues to brew in two of the world’s largest national economies of Spain and Italy. Conflict on Europe’s doorstep only serves to extend those risks with yet another major question mark.

Shorter-term, there’s a major level towards the middle of this mean-reversion, plotted at around 1.1700. This could be a potential resistance point to open the door for triggering short-side setups, with invalidation of the bearish idea at the current four-year-high of 1.2350: Once the string of longer-term lower-highs is broken, short positions wouldn’t as attractive.

See the EUR/USD Monthly Price Chart, below.

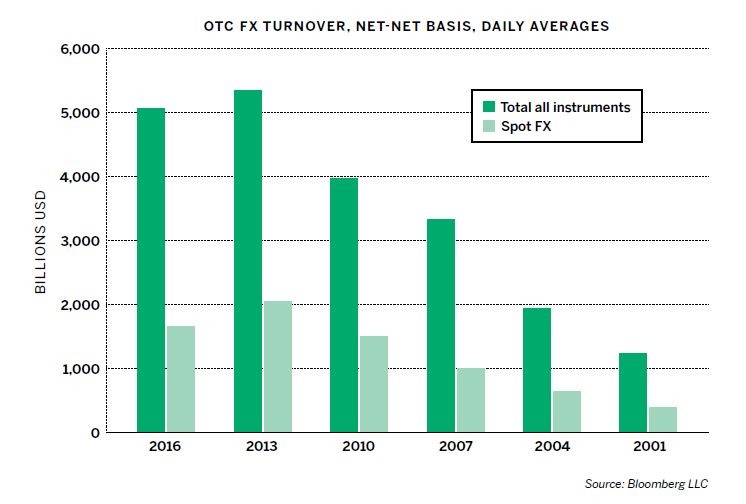

Euro Stoxx 50

Ever since the financial collapse there’s been a building fringe of bears looking to trade the collapse of the “super bubble.” And as central banks continued to stoke growth with easy money policies while amassing a massive portfolio, bears were continually stopped out as American equity markets rose higher and higher.

In Europe, that recovery didn’t take hold in quite the same way. Even today, prices in many European equity indices remain below the peaks of 2007-2008. And in the Euro Stoxx 50—the index representing 50 of the largest and most liquid companies in Europe, that string of lower highs has been building for more than 20 years, with the 2008 high remaining below the high from the year 2000, and last year’s high remaining below that 2018 high.

With central banks at an apparent turning point regarding policy, this could shift the tides a bit on stocks, and European equities may be in an even more fragile state than American equities. And as U.S. stocks begin to shift in anticipation of a move by the Fed, it appears that a similar theme has begun to show up in Europe with the Euro Stoxx 50 index.

The past nine months have seen prices oscillating between 4,000 and 4,300. Buyers have been thwarted on breakout attempts as prices reverted back into the range. The index may have topped out but if it hasn’t, breakout attempts would be signs of possible capitulation that would be quickly reversed.

The breakdown began to show as Russia invaded Ukraine, allowing for prices to fall through the 4,000 psychological level before finding support at the prior high of 3,769.

That support has led to a mild bounce thus far but the fact that sellers have already begun to push for lower lows highlights the fact that bearish moves may be around the corner as the Euro-zone sees both high inflation and slow grolwth amid the security crisis Russia has caused by invading Ukraine. That 4,000 evel is now resistance potential.

On the target side of the equation, deeper support potential exists around 3,500, after which the 3,361 level comes into play. A longer-term area of interest exists around the 3,000 level, and if that does come into play it would be a move of roughly 31.7% from the high set last November.

That seems reasonable given the circumstances. The final level is a price that may not come into play unless some larger theme takes over, such as NATO entering the situation in Ukraine, but that’s at the historically relevant 2,645, which is just over 40% from the high set last November.

If that price comes into play at some point in 2022, start looking at the long side of the index. But until then, focus on the short side of European stocks.

See the Euro Stoxx 50 Monthly Price Chart, below.